Hong Kong (CNN Business)China is riding out the trade war so far but its economic troubles run deep and could escalate rapidly if US tariffs really start to bite.

Beijing is already wrestling with other problems that the trade war could exacerbate. China's economy is now growing at its slowest pace since the global financial crisis. It's laden down with debt and facing concerns about a real estate bubble and weakening currency.

Despite the Trump administration's new tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods, exports are still growing strongly, up 16% in October. But that could change in the coming months if tariffs rise to 25% from 10% at the end of December, as the US has threatened, adding to China's growing list of problems.

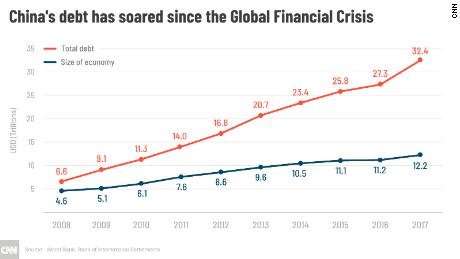

Runaway debt

The Chinese economy expanded rapidly in the years after the global financial crisis thanks to repeated debt binges.

"China's growth has been highly credit intensive," said Gerard Burg, Sydney-based senior economist at National Australia Bank. The total amount of debt in the Chinese financial system is now several times the size of the entire economy.

Some of this money has gone into building bridges, road and other infrastructure. But a lot has ended up in less productive parts of the economy, such as big, inefficient state-run companies. The more dynamic private sector hasn't benefited as much.

Late last year, Beijing stepped up its efforts to rein in the high levels of debt, which is one of the main reasons the economy is now losing momentum.

Some analysts are skeptical about the Chinese government's commitment to cleaning up its financial system, especially as the slowdown deepens and the trade war intensifies.

Many provincial governments and state-run firms would struggle to stay above water without regular injections of cheap credit, according to Kevin Lai, an economist at investment bank Daiwa Capital Markets.

Cutting off their credit lines "would have very negative repercussions, like social unrest, layoffs and bankruptcies," Lai said. That's a scenario Beijing wants to avoid.

Plunging currency

The government is also trying to fend off pressure on China's yuan, which has sunk more than 9% against the dollar since January. It's been hurt by concerns about the health of the Chinese economy and rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve that have pushed up the greenback.

The weaker yuan has boosted China's huge export industry, as it makes Chinese products cheaper on global markets. But slumps in the yuan have caused headaches in the past.

Amid sharp declines in 2015 and 2016, vast sums of money flooded out of China as investors bet the yuan would keep falling. The crisis forced Beijing to spend hundreds of billions of dollars to prop up its currency.

A rapidly falling yuan could become a vicious cycle, according to Manu Bhaskaran, the founder of Singapore-based research firm Centennial Asia.

"There could be a huge capital outflow and that could feed on itself," he said.

Beijing appears to have again started dipping into its massive war chest of foreign currencies in recent months to slow the yuan's declines, according to research firm Capital Economics.

Real estate bubble

Another threat lurks in the country's overheated property market.

Prices have more than doubled in the past decade, according to research firm Gavekal, stoked by low interest rates and a shortage of housing in major cities.

But the real estate market now "appears to be showing some cracks," said Aidan Yao, a senior emerging markets economist at AXA Investment Managers. He pointed to some instances of big property developers slashing prices in the face of weakening demand.

"It is only a matter of time before the market cools," Yao added.

The real estate industry has been one of the few bright spots for China's economy this year but turn into a burden if it slumps, according to analysts at research firm Fitch Solutions.

"This will add another layer of pressure," they wrote in a note to clients last month.

Chronic problems

Chinese officials have turned to tax cuts, infrastructure spending and looser monetary policy as they seek to prop up growth. But some experts think these are the wrong prescriptions for the country's economic woes.

"China's problems are chronic, not acute," said Derek Scissors, a China expert at the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington-based think tank.

In his view, the major issues, such as China's rapidly aging population and uncompetitive business environment, are being largely ignored.

The Chinese government has relaxed its decades-old one-child policy and tried to increase competition with plans to give foreign companies greater access in areas like banking and automobiles.

But those moves have come too late or don't go far enough, raising serious concerns about China's long-term economic future, according to Scissors.

"Old, indebted economies don't grow," he said