(CNN)NASA's Dawn spacecraft has run out of fuel and dropped out of contact with mission control, the agency said Thursday.

This ends the spacecraft's 11-year mission, which sent it on a 4.3 billion-mile journey to two of the largest objects in our solar system's main asteroid belt. Dawn visited Vesta and Ceres, becoming the first spacecraft to orbit two deep-space destinations.

Dawn missed two communication sessions with NASA's Deep Space Network the past two days, which means it has lost the ability to turn its antennae toward the Earth or its solar panels toward the sun. The end of the mission is not unexpected, as the spacecraft has been low on fuel for some time.

It's the second historic NASA mission this week to run out of fuel and come to an end, as NASA's Kepler Space Telescope did Tuesday.

"Today, we celebrate the end of our Dawn mission -- its incredible technical achievements, the vital science it gave us and the entire team who enabled the spacecraft to make these discoveries," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. "The astounding images and data that Dawn collected from Vesta and Ceres are critical to understanding the history and evolution of our solar system."

Vesta and Ceres are considered to be like time capsules from the beginning of our solar system. The experiments Dawn carried out enabled astronomers to look at the different ways Vesta and Ceres formed and evolved, as well as revealing that dwarf planets can also host oceans.

Vesta probably formed in the inner solar system and stayed between Mars and Jupiter, and it evolved just like the other rocky planets there. Its craters provided a road map of impacts on the ancient surface, suggesting that large planets crashed into it. This also suggests that planets were "born big," rather than starting small and growing.

Ceres formed farther from the sun and migrated to the same area of the inner solar system. On the surface, Dawn found ammonia, which requires the cold temperatures of the outer solar system to form.

Vesta didn't have as much water as Ceres, so it melted its own interior to form a metallic core and rocky crust, while Ceres has a rocky clay-like mantle and an outer ice-water-rich shell. This is why the scientists studying Dawn's data believe that Ceres once hosted an ocean, and there could even be liquid beneath the surface.

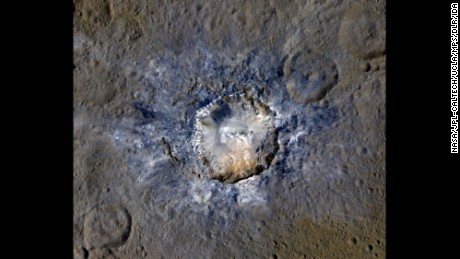

Dawn also detected an abundance of organic molecules in one of Ceres' craters, which might have come from the planet's ocean. On Earth, these same organic molecules are associated with life.

Bright features on the dark surface of Ceres and a giant, lone volcano suggest that the dwarf planet's surface has been geologically active recently.

"The fact that my car's license plate frame proclaims 'My other vehicle is in the main asteroid belt' shows how much pride I take in Dawn," said Mission Director and Chief Engineer Marc Rayman at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "The demands we put on Dawn were tremendous, but it met the challenge every time. It's hard to say goodbye to this amazing spaceship, but it's time."

Dawn will remain in orbit around Ceres for at least the next 20 years, although the engineers putting it into this orbit are confident that it could last 50 years. They don't want it to collide with Ceres because there is a chance that it could disrupt some intriguing chemistry on the dwarf planet -- chemistry that could lead to the development of life.

"In many ways, Dawn's legacy is just beginning," Principal Investigator Carol Raymond at JPL said. "Dawn's data sets will be deeply mined by scientists working on how planets grow and differentiate, and when and where life could have formed in our solar system. Ceres and Vesta are important to the study of distant planetary systems too, as they provide a glimpse of the conditions that may exist around young stars."