Story highlights

Black and Hispanic preterm babies, compared with white, had increased risk of severe health issues in a new study

The study suggests that health disparities among preemies may be larger than thought

A new study suggests that black and Hispanic premature babies, compared with white premature babies, had a two- to four-fold increased risk of four severe neonatal health problems.

Those health problems included necrotizing enterocolitis, which impacts tissue in the intestine, and intraventricular hemorrhage, which is bleeding in certain areas of the brain, both of which can be deadly; bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a lung condition that might result in long-term breathing difficulty for some; and retinopathy of prematurity, an eye disorder that can be potentially blinding.

Additionally, Asian preterm infants were at an increased risk of retinopathy of prematurity, according to the study published on Monday in the medical journal JAMA Pediatrics.

The findings suggest that previous research on disparities in these preterm morbidities – a term to describe diseases or medical problems – have underestimated “the true magnitude of disparity,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Previous research indicated that disparities were minimal, likely because of how the studies were designed, said Teresa Janevic, an assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and first author of the study.

Yet “our study estimates risk of very preterm morbidities from the vantage point of all pregnancies, and therefore better captures population-level disparities,” Janevic said.

Globally, preterm birth complications are the leading cause of death among children under 5 years old. Every year around the world, an estimated 15 million babies are born preterm – before 37 completed weeks of gestation – and the number is rising, according to the World Health Organization.

‘The magnitude of the disparities is striking’

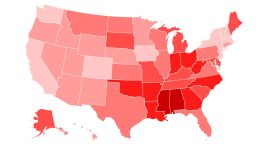

In the United States, preterm birth affected about one of every 10 infants born in 2016 and the preterm birth rate among black women was about 50% higher than among white women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In the new study, “we were not surprised to find that black and Hispanic infants are at higher risk of very preterm morbidities given what we know about their increased risk to be born extremely premature, as well as our previous work that hospital quality of care may play a role in racial and ethnic disparities in very preterm morbidity,” Janevic said.

“However, the magnitude of the disparities is striking,” she said. “Also, we were somewhat surprised regarding the finding of increased risk of retinopathy of prematurity among Asian very preterm infants, a finding that needs to be researched further to replicate and potentially explain.”

The new study involved data on 582,297 infants in New York City who were born very prematurely, at 24 to 31 weeks’ gestation, between 2010 and 2014, and then later died between 2010 and 2015.

The data – which included birth certificates, hospital discharge records, and mortality data – came from the New York State Department of Health’s statewide planning and research cooperative system.

The researchers analyzed the prevalence of the four severe neonatal morbidities within the data, taking a close look at differences by race and ethnicity.

Once the researchers adjusted the data for various factors – such as socioeconomic status or the mother’s health – they found that black infants compared with white infants had an increased risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and a borderline increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis.

Hispanic infants had a borderline increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis and intraventricular hemorrhage, and Asian infants had an increased risk of retinopathy, the researchers found.

The study had some limitations, including that the diagnosis of morbidities as well as coding practices could vary across hospitals, and the researchers did not have detailed information from medical records for each infant to help explain reasons for the disparities.

More research is needed to determine exactly what factors are driving these disparities, but Janevic offered some ideas.

“Quality of care, both for the mother and the very preterm infant, likely plays a role, as well as a wide range of social, environmental and biological exposures to the developing fetus,” she said. “In our study, black and Hispanic infants were more likely to be born very preterm than white infants, which explains in part the wide disparities in morbidities.”

‘These findings … should cause us to redouble our efforts’

Michael Kramer, an associate professor of epidemiology at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, called the new study “thoughtful” and “rigorously carried out” – and he noted that the large disparity found in the study corresponds with disparities in health risk factors among mothers-to-be.

So the health disparity seen among premature babies could be related to health disparities seen among pregnant women as well.

Among pregnant women, “there is growing evidence that chronic stress associated with poverty and exposure to discrimination can lead to behavioral changes including substance use; but they can also directly affect biological changes in inflammation, neuroendocrine function, and vascular function, each of which increases the risk of prematurity,” said Kramer, who was not involved in the study.

Neuroendocrine function involves interactions between the nervous system and hormones, and vascular function involves the health of your blood vessels.

“There is no evidence in this study that there is anything at all normal about shorter gestation for black women for instance,” Kramer said. “Quite the contrary, these findings of very large racial and ethnic disparities should cause us to redouble our efforts to understand not only the biological but also the behavioral and social determinants of racial differences in health.”

Overturning a commonly held misconception

The new study appears to challenge a commonly held misconception in some neonatal intensive care units that black infants are more likely to survive treatment than their white counterparts, said Dr. Heather Burris, an attending neonatologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study.

For instance, a previous paper published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology in 1996 came to that conclusion among infants delivered at Chicago-area hospitals, suggesting that black infants born preterm fared better than white infants born preterm.

Now, the new study “really supports that that’s not true, that in fact African-American infants do not do better and may even do worse than their white counterparts,” Burris said.

As to why this disparity exists, there are many potential explanations, she said.

“One could be on the health care side, in other words, what the physicians and nurses do. Are there times when there are differences in care that result from potential cultural practices or maybe even implicit bias? That’s one hypothesis,” Burris said.

Another possible factor could be the reason as to why a preterm delivery occurred in the first place. If the reason was a certain pregnancy complication that varies by race, that complication could contribute to a higher risk of morbidity among the infant, which subsequently could vary by race also, she said.

Yet in general, this disparity among preterm infants remains difficult to examine because, “the other piece is that death is not a random event in the NICU most of the time,” Burris said.

“The way that most babies die in the neonatal intensive care unit is that they have a complication and the decision is then made to stop intensive care and to provide comfort care,” she said. “There may be potential racial disparities in that practice, making this data somewhat difficult to interpret. It’s a limitation of all outcome studies of preterm infants because that’s an individual conversation that happens between the family and the provider.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

All in all, the ability to better understand the serious consequences of infants being born premature remains critical, Dr. Lisa Waddell, deputy medical officer of the nonprofit March of Dimes, said in a written statement to CNN on Friday.

“We know that there are disparities in the numbers of babies being born preterm and that being born too soon often leads to poorer birth outcomes. The findings in this article make logical sense in that similar disparities in severe neonatal morbidities also occur,” the statement. “This report reinforces the urgency of supporting women before, during and after pregnancy and preventing preterm births in women of color and all women.”