Story highlights

2017 was hottest year without an El Nino

Sea levels reached all-time high

Last year was one of the hottest in recorded history, according to a new study released Wednesday by the American Meteorological Society.

The report is another piece of compelling evidence that our planet is warming faster than at any point in modern history. It’s the 28th version of the annual checkup for the planet and updates numerous global climate indicators such as polar ice, oceans and extreme weather events around the world.

The State of the Climate in 2017 report, led by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Centers for Environmental Information, was compiled using contributions from more than 500 scientists in more than 60 countries.

The fact that 2017 was either the second- or third-hottest year, depending on the dataset used, does not come as a surprise. It follows a string of record hot years in 2014, 2015 and 2016 – and while 2017 did not provide a fourth consecutive record, it was the hottest non-El Niño year seen.

El Niño, which is characterized by a warming of the equatorial Pacific Ocean, tends to warm up the entire planet during years when it occurs.

Conversely, when La Niña is active, it tends to provide some natural air-conditioning for the planet as large portions of the Pacific Ocean cool to below average temperatures. Even though 2017 had a weak La Niña present in the beginning and end of the year, it failed to regulate the planet’s high temperature caused by ever-increasing amounts of greenhouse gas concentrations.

Billion-dollar disasters in 2017

The major greenhouse gasses, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane and nitrous oxide, all rose to record high amounts in our atmosphere during 2017, according to the report.

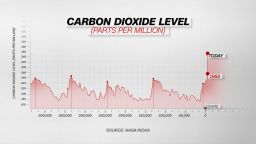

The global average carbon dioxide concentration was 405.0 parts per million (ppm), which is the highest ever recorded and also higher than at any point in the last 800,000 years, according to ice-core data.

Oceans heating, rising

The oceans are also heating up, with significant planet-altering consequences.

The global average sea surface temperatures were near a record high, just slightly below the record from 2016, and the last three years have seen the hottest on record.

Warm seas equal rising seas, and 2017 set a new record for global sea level – which has risen year over year for six consecutive years and 22 of the last 24 years. Global sea level is rising at an average rate of 1.2 inches (3.1 cm) per decade, and that rate has been even higher in the most recent decades as sea-level rise accelerates.

Unprecedented coral bleaching also occurred during 2017, according to the report, which was the most widespread and destructive ever observed with hundreds of miles of corals in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Ocean basins experiencing up to 95% mortality in the hardest-hit reefs.

Both poles see record low ice

Both the Arctic and the Antarctic saw record low levels of sea ice during 2017, as warmer air and sea surface temperatures continued the trend of thinning out the polar ice.

“Today’s abnormally warm Arctic air and sea surface surface temperatures have not been observed in the last 2,000 years,” the study said.

In March of 2017, at the end of the ice-growing season when the coverage of sea ice in the Arctic reached its maximum extent of the year, scientists found it was the smallest yearly maximum in the 37-year record.

In the Antarctic, sea ice was below average for all of 2017, hitting record lows during the first four months of 2017. On March 1 it hit a record low extent since satellites began observing the ice in 1978.

As for land ice, the news continues to be grim, which is bad news for global sea levels as melting glaciers are a significant contributor to rising ocean levels.

Glaciers across the globe lost ice mass for the 38th consecutive year – with declines “remarkably consistent” across all regions of the planet according to the report. To put the amount of ice lost since 1980 into perspective, the report states that “the loss is equivalent to slicing 22 meters (more than 70 feet) off the top of the average glacier.”

Extreme storms and rainfall

“Climate is not experienced in annual averages,” the report states, even though that is how we most often monitor and gauge the changes in our planet’s climate variability – both natural and human-influenced.

“Humans experience climate change and variability most deeply in the form of impacts and extremes,” according to the report — and 2017 certainly had plenty of them.

Even though globally tropical cyclone (hurricanes, typhoons, tropical storms, etc.) numbers were about average in 2017, the North Atlantic basin had one of it’s busiest years on record with three standout hurricanes.

Hurricane Harvey dumped record rainfall totals in Texas and Louisiana, including a new US record of 60.5 inches (1,538 mm) which smashed the old record of 52 inches (1,320 mm).

Right on it’s heels came Hurricane Irma, which became the strongest tropical cyclone globally of the year and the strongest Atlantic hurricane outside of the warmest waters of the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean.

Hurricane Maria immediately followed, bringing catastrophic damage across the Caribbean Islands including devastating the landscape and infrastructure of Puerto Rico.

All three of these hurricanes ranked in the top-5 costliest disasters in US history.

Notable, deadly floods hit every continent except Antarctica – with India floods claiming 800 lives, Venezuela experienced its most devastating flooding in more than a decade, and flooding of the Niger and Benue Rivers in Nigeria displaced more than 100,000 people.

Global fire activity was the lowest since at least 2003, but extreme droughts in a few key locations led to a number of devastating fire seasons globally.

In the US, an extreme western wildfire season saw over 4 million hectares burned, costing $18 billion – which tripled the previous US annual wildfire cost record from 1991. Just to the north, Canada’s British Columbia saw 1.2 million hectares burn during their driest summer on record.

Spain and Portugal had their second- and third-driest years respectively – and suffered through an unusually long fire season that claimed over 100 lives.