Story highlights

Gift-giving has emotional, social and moral lessons for both the giver and receiver

Birthday gifts are buffers against the vulnerability we feel when forced to acknowledge another year

We were the first birthday party in my son’s class this year, and as per the custom, we sent out an invitation free of any mention of presents.

When the day arrived, we guilelessly directed guests to place gifts in a corner of our living room, ignorant of the faux pas we had committed.

It was not until I recaeived the third or fourth consecutive invitation for his classmates’ parties, all of which contained a bold-printed mandate to not bring gifts, did I realize what we had done.

Knowingly rejecting a local custom can be invigorating. But blindly breaking ranks with the status quo tends to lead to unease. I didn’t exactly regret asking for presents – or, more specifically, not asking for no presents – but wished that I hadn’t done it in a state of ignorance.

The year went on, and only two of around the 15 birthday party invitations we received did not contain a “no presents” mandate. Clearly, my instinct to permit presents at my child’s birthday party had made me an outsider. I began to question my instincts.

The no-presents birthday party trend took off about a decade ago and has since continued to spread among well-meaning parents coast to coast. Might all these people be right? Are birthday presents merely a capitulation to a materialistic and consumerist society, a soon-to-be vestige of 20th-century overabundance? It’s an idea I sympathize with but not one I am ready to get behind.

Before I tell you why, it’s important to note that, like most matters surrounding parenting, there is no right answer here. Unlike vaccinations (please vaccinate), eschewing birthday presents should be a matter of personal discretion. What follows is not an attack the “no-gifters.” It’s a defense of presents and an exploration of the emotional, social and moral lessons they offer both the giver and receiver.

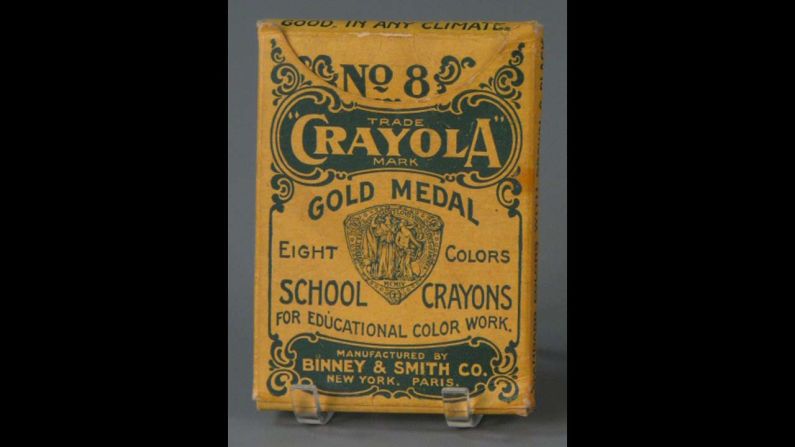

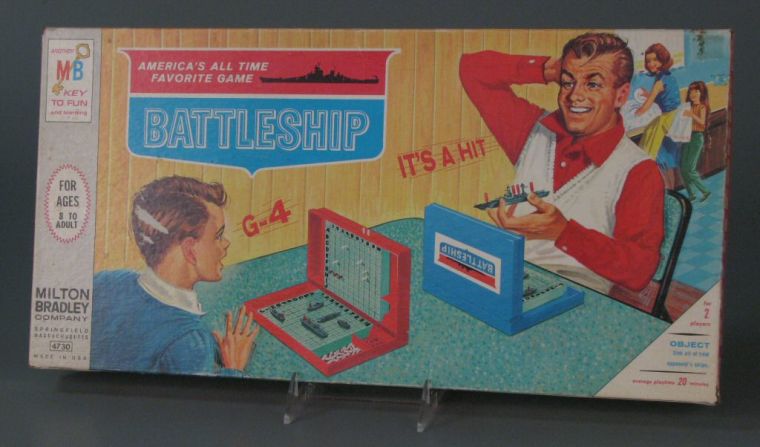

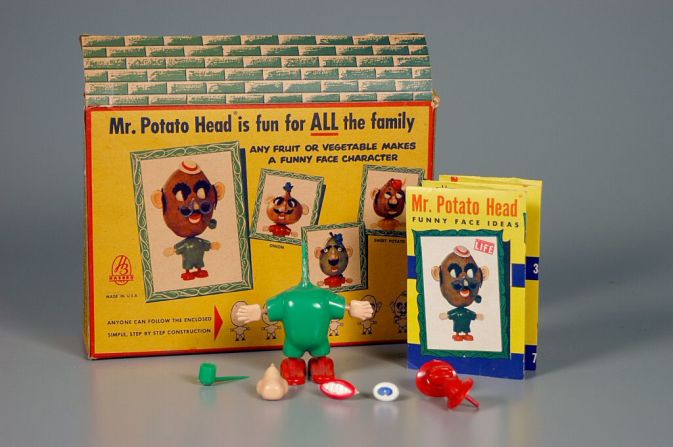

The gift-giving process can be soulless. Parent hastily orders a plastic something or other online a Prime-friendly two days before the party. The child on the giving end has no idea what it is, and the child on the receiving end spends a total of seven minutes playing with it before dumping it into the toy bin and forgetting about it forever.

But the gifts themselves aren’t to blame. It’s the process through which the gifts were obtained, given and received that is at fault.

Gifts teach children about generosity

Here is an alternative scenario: I recently took my 5-year-old son to the toy store to pick out something for his classmate’s birthday party (one of the two that didn’t forbid it). After a few minutes, during which he simply couldn’t help but think about himself, he pivoted to contemplating who his friend is and what he might desire.

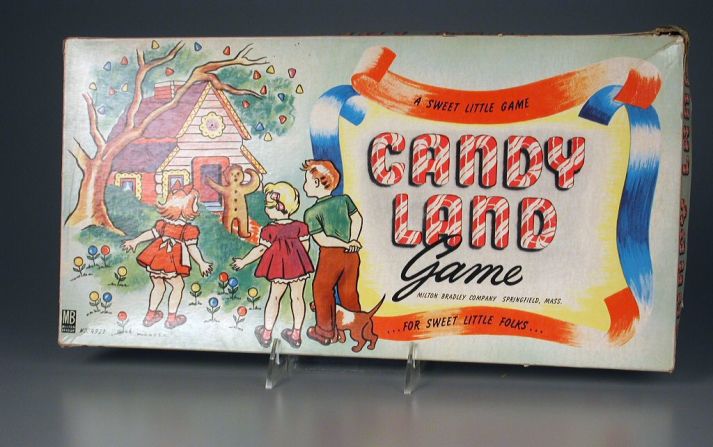

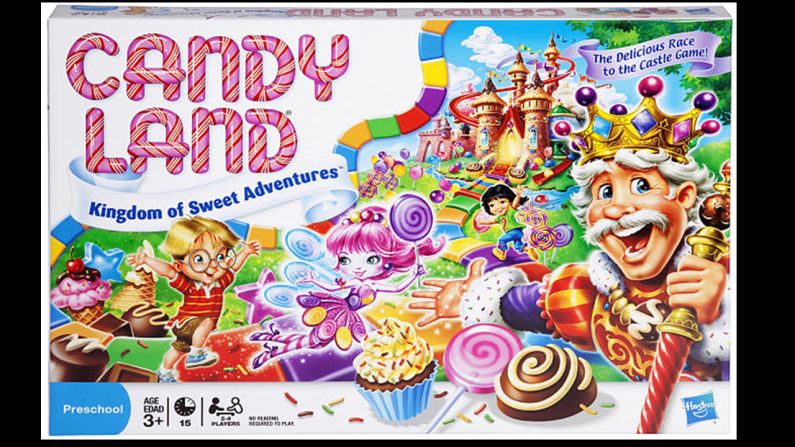

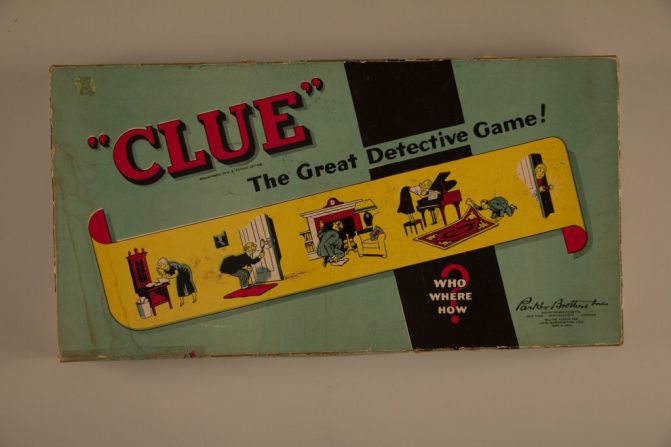

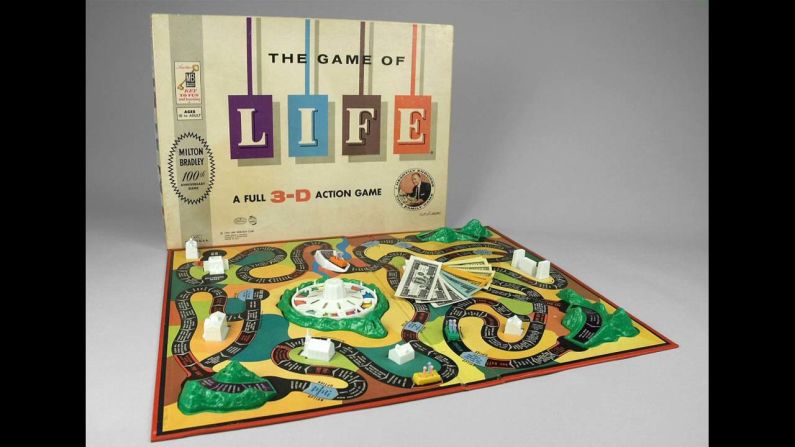

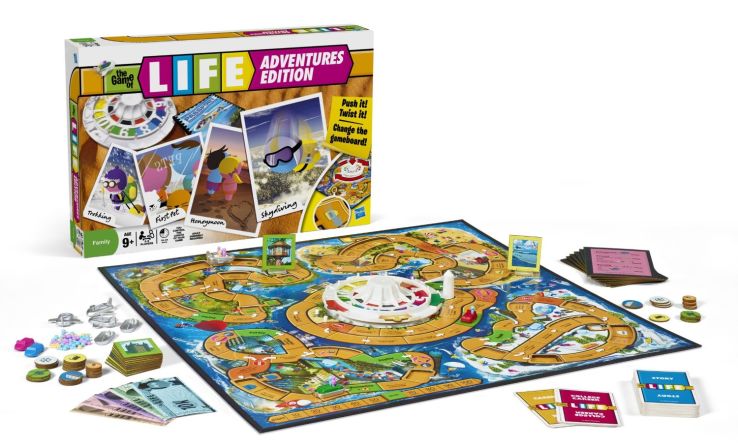

After determining that there were no werewolf-themed products available, he moved on to the broader category of “scary” or “mysterious” toys. With a bit of encouragement from me, we settled on the board game Clue Jr. And because my son is (like most children his age) completely emotionally transparent, I can say with certainty that he left the toy store feeling really good about the selection.

“We tend to think of them as selfish creatures, but the data suggest that children find giving rewarding just like adults do,” said Lara Aknin, assistant professor of psychology at Simon Fraser University, who has studied generosity in children. She explained that giving young children opportunities to behave generously is important because when people discover that they like something, they tend to want to do it again.

Choosing Clue Jr. for his friend was a valuable lesson in generosity for my son. He had to think of someone else in an environment in which his id was screaming “Me! Me! Me! Mine! Mine! Mine!” and consider the world through another’s eyes. This is not a giant sacrifice in the cosmic sense, but for a kindergartner, it’s pretty big.

Giving is most likely to increase the giver’s happiness when three conditions are met, Aknin said: when there is an element of social connection between giver and receiver, when the giver has some understanding of the impact the gift will have on the receiver, and when the giver feels some sense of autonomy when choosing the gift. The more a child is involved in the decision-making behind a gift, the more they will experience a “warm glow” from delivering it.

Aknin said that although the researchers have tested these conditions only with adults, she suspects that they would be similar for children.

Of course, birthday presents are hardly the only arena in which one can foster generosity in children, but it is a valuable one. Birthdays give children (who are often not aces at abstract thinking) an opportunity to meet all three conditions and thus fully grasp the importance of giving.

“Generosity helps knit our social lives together … and function as a larger collective,” Aknin said. “Gift-giving, and helping others more broadly, helps us navigate and smooth our social world.”

Researchers who study generosity and gift-giving have found evidence of its importance in a variety of cultural and socioeconomic settings. Mary Jo Katras, program leader of the Family Resiliency team at the University of Minnesota Extension Center, has studied the function of birthday parties among low-income families. She explained that these parties, including the gifts, are something families are willing to make economic sacrifices for. They often cut back in other areas or seek help from friends and families in order to make them happen.

Katras said that, like in other communities, the act of gift-giving among low-income families is an important ritual that “helps a child learn the importance of thinking about the happiness of another person.” Importantly, it’s not about the gift, per se, but the giving of the gift that really matters.

“Focusing on the act of giving teaches children that the gift does not have to be extravagant and expensive,” Katras said. “The gift can take on many forms: a tangible gift, a gift of time or a gift of service. Just something that honors the person being celebrated.”

Why we need presents on our birthday

As much as we love to project an aura of unfettered joy around birthdays, they are, in reality, a bit dark. The act of counting one’s years puts us in direct contact with our mortality. Even children, who tend to be less death-minded than adults, have a keen understanding of the irreversibility of time and experience it acutely around their birthdays.

More so, milestones that are supposed to be happy, like birthdays, have a way of highlighting the parts of our life that don’t measure up. We know we are supposed to celebrate what is, but many of us can’t stop our minds from drifting to what isn’t.

Historically, birthday presents were given to appease spirits, good and bad. While most of us have moved on to to either monotheism or atheism, the ritual of gift-giving still plays a similar function. They are buffers against the magnitude of the day, of the vulnerability we feel when faced to acknowledge our lives and another year come and gone.

So instead of banning presents, we could try to do them better.

Kelly Vockell, owner of Cherry on Top Parties, a children’s party-planning business in Scottsdale, Arizona, and the San Francisco Bay Area, said parents should think about using presents to cultivate gratitude in their children. She cautions parents about allowing children to open gifts in front of guests, where they tend to tear through things without paying much attention.

“Put them in a back room, and then do it afterward in a leisurely and supervised way, encouraging the child to be gracious,” Vockell said. She also believes that children should take part in the writing of the thank-you cards, which will further help them recognize both the gift and the gift-giver.

For those fearful of the clutter created by presents, Vockell has two suggestions. Parents of the birthday boy or girl can encourage a toy cleanse before the party. Parents who would like to give something special but don’t want to add yet another toy to their child’s pile should consider giving experiences over physical items. These need not be expensive, and there’s a lot of room for creativity and personalization.

My son, for example, would love a “movie night” present, in which he was invited to go to the theater or watch Netflix at a friend’s house surrounding by drugstore candy and microwave popcorn. Among this gift idea’s fans would be my husband and me, who would be thrilled with an evening of free babysitting.

Join the conversation on CNN Parenting's Facebook page

Vockell is wary of the urge to fold adult-led minimalism into all aspects of children’s lives, and birthday celebrations in particular. She said the no-presents parties she’s experienced often also involve a ban on sugar, food coloring and party favors.

“Birthday parties are an opportunity to celebrate a magical and fleeting moment in a child’s life and create some of the most cherished childhood memories. The anticipation of treats and presents is part of that,” she said. “I find it kind of a pity when parents push their agenda on children in this way.”

Considering the significant rise in anxiety among children today, we parents should be looking for any chance to provide our children with fun for fun’s sake. A pile of presents with their name on it is not merely more stuff. It’s a portal into a sense of community and joy, the kind of unmitigated pleasure that gets harder and harder to find as we grow up.

Elissa Strauss writes about the politics and culture of parenthood.