Story highlights

A fever early during pregnancy is known to cause some heart defects and a cleft lip or palate

Researchers demonstrated it is the fever, and not underlying infection, that causes birth defects

Running a high fever during early pregnancy is known to be dangerous.

A first-trimester fever can increase a baby’s risk of developing a congenital heart defect and certain facial deformities, such as cleft lip or cleft palate.

But is it the fever or the underlying infection that causes the defect?

A new study published Tuesday in the journal Science Signaling reveals it’s the fever itself that interferes with the development of a baby’s heart and jaw during the first three to eight weeks of pregnancy.

“We need to increase public awareness regarding fevers and birth defects. Women are often hesitant to take medication during pregnancy,” said Dr. Eric Benner, senior author of the study, and a neonatologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at Duke University.

“Doctors should counsel women about the risk of fever and remind them that Tylenol (acetaminophen or paracetomol) is one of the most well-studied drugs in pregnancy and is thought to be safe,” said Benner.

He added that women should ensure they discuss all the risks and benefits of taking medication during pregnancy with their doctors.

Scientific serendipity

Like many scientific discoveries, the new finding is “somewhat accidental,” said study co-author Chunlei Liu, an associate professor in electrical engineering and computer sciences at the University of California, Berkeley.

The discovery came about while he and Benner were developing a way to change the activities of cells by focusing on temperature sensitive ion channel proteins. Ion channels work like mini transportation tunnels in cell walls, allowing the flow of ions (electrical currents) in and out of cells.

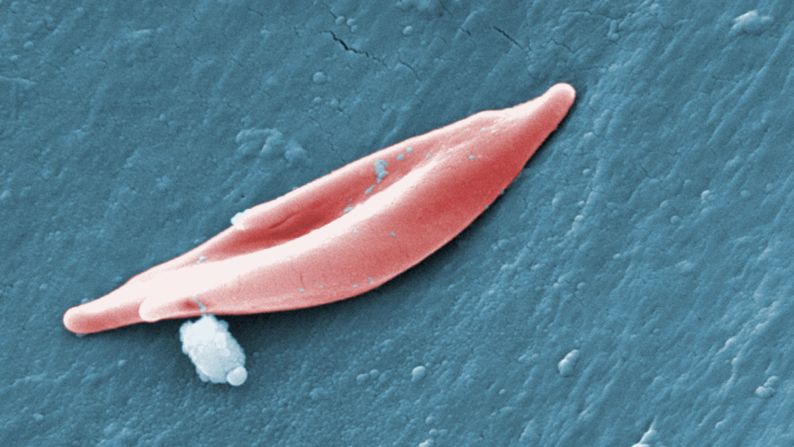

The research team focused on neural crest cells, which are critical building blocks for the heart, face and jaw.

Through experimentation, Liu and Benner discovered that the ion channels of these crest cells were sensitive to temperature. Typically, temperature-sensitive ion channels are found in those brain cells that send signals to help your body understand, say, that the temperature has changed when you stick your hand in hot water.

The researchers speculated that changing calcium activities of neural crest cells might in turn reproduce some congenital heart defects, Liu explained. So they decided to conduct their experiments on chicken embryos and collaborated with Mary Redmond Hutson, a Duke researcher and lead author on the study who specializes in learning how congenital heart defects occur.

First, the team engineered a magnet-based technology capable of raising the temperature in two specific ion channels within the neural crest cells of the chicken embryos. The temperature-sensitive ion channels are called TRPV1 and TRPV4. Essentially, then, the researchers created a fever in the embryos by manipulating these channels.

Sure enough, following this synthesized fever during early development, the chicken embryos developed facial disfigurements and heart defects.

The bottom line: heat activation of the ion channels alone was sufficient to result in birth defects – no infection was necessary.

“It shows that hyperthermia (fever) is important for the genesis of these serious birth defects,” said Benner.

However, he noted that they still do not understand whether the severity or duration of high temperature might impact the defectsfurther.

Raising awareness

“Typically, birth defects are thought to be genetic in origin,” noted Benner. Yet, past studies have linked fevers to a variety of birth defects, including cleft lip or cleft palate, certain types of heart defects, and neural tube defects commonly called spina bifida.

While congenital heart defects affect 1% of live births in the United States, genetic mutation can only explain about 15% of them, said Liu. He added that “most of them have unknown causes.”

The reason it is “exciting” to demonstrate that running a fever during pregnancy may also cause harm is because “fever-associated defects are preventable,” said Benner.

Prevention may be as simple as reducing fever by taking over-the-counter medication – but only after discussing this with a doctor.

“We hope that this will raise an awareness among doctors that fever during the first trimester can directly contribute to congenital heart and cranial facial defects,” said Liu, who added that it is necessary to continue studying the effects of heat on these ion channels in humans.

Dr. Brad Imler, president of the American Pregnancy Association, agreed this “must be pursued and studied further.” Imler and the association, which is committed to promoting reproductive and pregnancy wellness through education, advocacy and community awareness, were not involved in the research.

“It is always imperative for expecting mothers to contact their health care providers when experiencing a fever during pregnancy,” said Imler.

It’s not only the connection to possible birth defects, said Imler, it’s that “fevers also represent some other potentially hidden complication, that needs to be diagnosed to determine additional risks to both mom and baby.”

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Dr. Geeta K. Swamy, a Duke Health maternal-fetal medicine specialist who was not involved in the study, said that fevers are not uncommon during pregnancy.

“Proper hand-washing techniques and the flu vaccine are two preventive measures women can take to reduce their risk of developing an illness with fever,” she said. And, when treating a fever, a pregnant woman “should not use aspirin, ibuprofen or naproxen.” Acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol, is best.

Generally, Imler noted, fevers are “unfriendly” to the health and wellness of the developing baby.

“This is why expecting mothers are advised to avoid hot tubs and saunas which can elevate the temperature within the womb,” said Imler.