Editor’s Note: Nina Schick is a European political commentator and consultant specializing in EU policy, German politics and Brexit. She previously worked at the independent think tank Open Europe. The opinions in this article belong to the author.

Political upset and change – the twin themes dominating Western politics of late – have led to Britain’s voting to leave the EU, the election of Donald Trump and, most recently, in Emmanuel Macron’s ascendancy to the Elysée Palace in France.

Anything but the status quo everywhere, it seems. Well, nearly everywhere.

Six weeks ahead of Germany’s national elections, Chancellor Angela Merkel launched her bid for reelection last weekend in Dortmund, a small city in Germany’s industrial heartland and the country’s most populous state.

Unlike other deeply polarizing elections in Europe (and the US), don’t expect this one to get too heated. There will be no fire and brimstone from Merkel: she will run a calm – maybe even bland – campaign.

Posters for Merkel’s Christian Democratic Party (CDU) give a hint as to what’s likely to follow. “Enjoy the summer now, and make the right choice in the fall,” one of them tells voters, with a picture of a smiling young woman lying in a field.

So can Merkel be stopped? It seems unlikely. She has won seven straight votes since she was first elected to parliament in 1990. And she will almost certainly win a fourth term as Chancellor in September, marking over a decade in power, and bucking the trend seen in other Western liberal democracies.

Her most recent approval rating, released on Thursday by Infratest Dimap, suggests that a whopping 59% of Germans think that “Mutti” is doing a good job. Other leaders would kill for numbers like these. For Merkel, there’s room for improvement: it’s 10% down from last month.

What about her competition? At the moment it looks likely it’ll be blown out of the water.

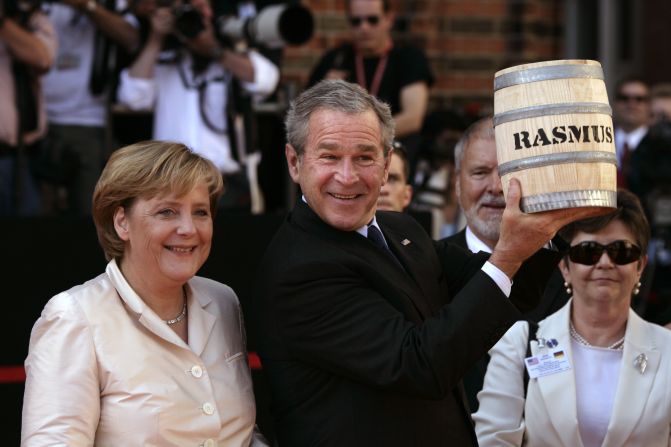

Angela Merkel's life in pictures

Martin Schulz – leader of the center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) and former president of the European Parliament – promised to shake things up when he entered the political fray earlier this year, hoping to unseat Merkel.

At first his campaign dealt in emotional political rhetoric and seemed to be making headway. Column inches were filled with articles about “the Schulz Effect” as the SPD was neck-and-neck with Merkel’s CDU in some polls.

And then it fell flat. The SPD made big losses in three regional elections that serve as bellwether of the national vote, including a painful defeat in North-Rhine-Westphalia, a traditional SPD heartland and the state that Dortmund happens to call home.

The task ahead seems nearly impossible now for the SPD. “The SPD is Burning,” read an editorial in the respected German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung last week.

What’s Merkel’s big secret? Being Angela Merkel.

That means staying cool, calm and pragmatic, even in the face of the most difficult circumstances. Don’t forget that she has weathered numerous crises in the last few years.

At the height of the eurozone crisis (remember those tense hours ahead of the 2015 “Greferendum,” when Yanis Varoufakis jetted back and forth to Brussels, and it looked like Greece would be thrown out of the common currency?) it was Merkel who spent political capital to keep the bloc together.

Then there was the Ukraine crisis – catalyzed by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s particularly boisterous brand of nationalism – which saw Merkel take the lead in placing EU sanctions on Moscow, despite Germany’s close economic links to Russia.

Merkel’s biggest “wobble” came during the 2015 migration crisis, when over a million refugees and asylum seekers came to Germany, forcing temporary border controls and heated public debate, domestically as well as internationally. As her approval ratings tumbled, some (mostly Anglo-Saxon) commentators were overzealous in predicting her imminent demise and the hijacking of German politics by the right-wing and anti-immigrant AfD party.

And yet, she persisted, telling Germans that “we will manage.”

And that’s the thing: they believe her – much to the disbelief of some political observers. In this increasingly unstable world, German voters want their capable manager to remain in post. They want her to protect what matters to them most: the economy, and the European Union.

And in Germany there is no cause for great alarm. The economy is doing well, unemployment is at a low, and even the refugee crisis seems to have abated (for now).

Germans don’t want a political revolution. So why would they take a risk?