An investment group that U.S. authorities say is run by Russian mobsters and linked to the Russian government sent at least $900,000 to a company owned by a businessman tied to Syria’s chemical weapons program, according to financial documents obtained by CNN.

According to a contract and bank records from late 2007 and early 2008, a company tied to a state-backed Russian mafia group, according to U.S. officials, agreed to pay more than $3 million to a company called Balec Trading Ventures, Ltd — supposedly for high-end “furniture.”

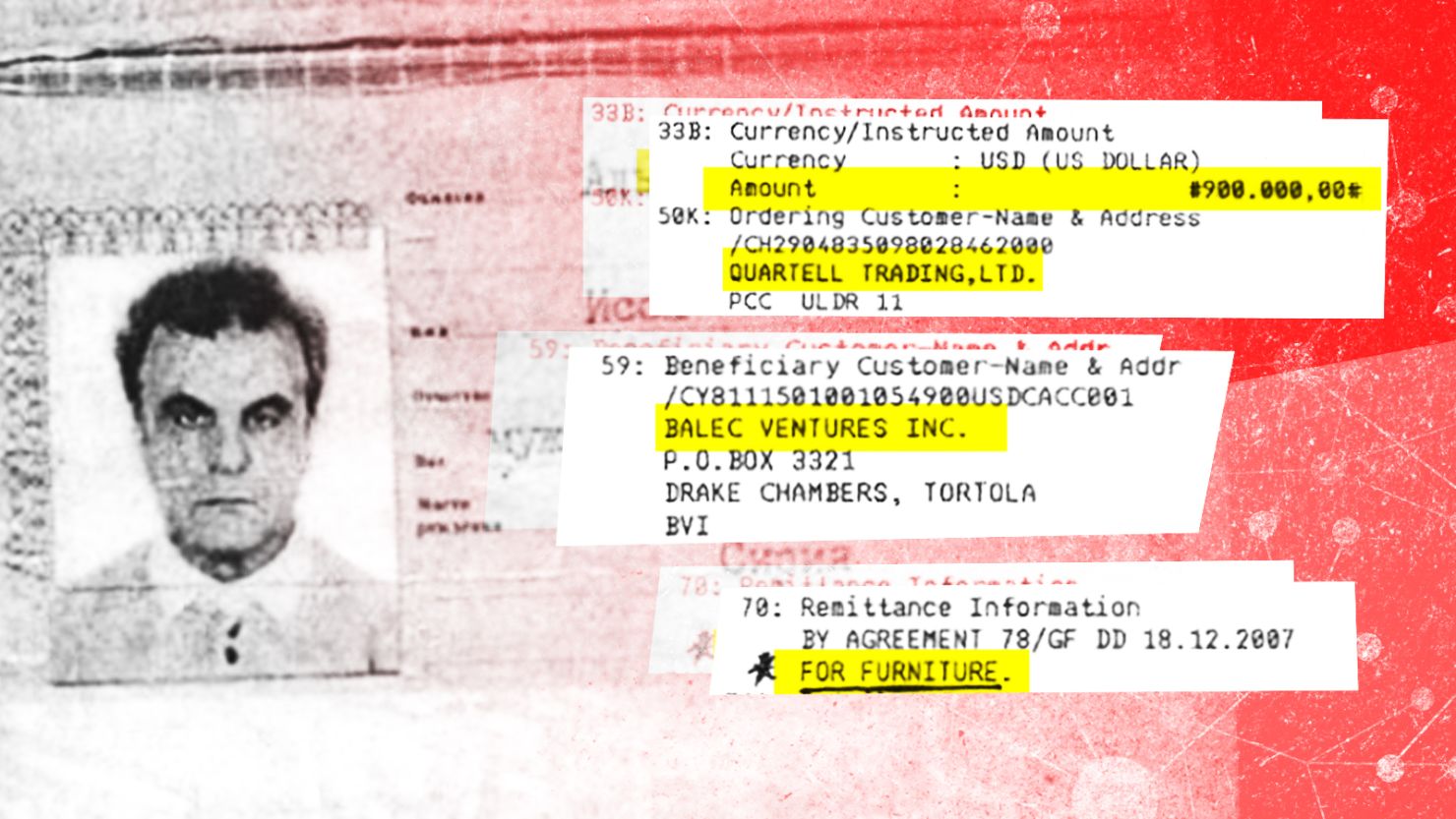

Wire transaction records seen by CNN confirm that at least $900,000 was transferred.

Both businesses are registered in the British Virgin Islands.

The company allegedly tied to Russian mafia was called Quartell Trading Ltd., and the U.S. Department of Justice claims it is one of the many vehicles into which millions of dollars of stolen Russian taxpayer money was laundered a decade ago in connection with the so-called “Magnitsky affair,” perhaps the most notorious corruption case in Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Balec Ventures is owned by Issa al-Zeydi, a Russian whom the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned in 2014 for his connection to the Scientific Studies and Research Center, the hub of Syria’s nonconventional weapons program, including its manufacture of Sarin and VX nerve agents and mustard gas.

The $230 million tax fraud

According to U.S. Congress and the U.S. Department of Justice, a band of Russian mafia called the Klyuev Group consists of past and present officials in the Russian Interior Ministry, two Moscow tax bureaus and the Federal Security Service, or FSB, the domestic intelligence service and successor body to the Soviet KGB.

In 2007, authorities say, the Klyuev Group, colluded to fraudulently seize the ownership of three subsidiary companies connected to a Moscow-based Hermitage Capital Management, then the largest hedge fund in Russia.

The Klyuev Group then fabricated hundreds of millions of dollars in losses for these companies that they had taken over. That enabled them to apply for a tax refund of $230 million.

The entire amount was processed in a single day, Christmas Eve 2007, by Russian tax officials on the Klyuev payroll.

Sergei Magnitsky, the lawyer hired by Hermitage Capital to investigate the theft, uncovered this vast criminal conspiracy and the players behind it. He was arrested in 2008, denied urgent medical care for over a year in pretrial detention and physically tortured before his death in Moscow prison in 2009 at age 37.

In the years since, the case has become an international cause celebre, prompting diplomatic protests and even legislative action in the West.

In 2012, Congress passed the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act, under which some three dozen Russian officials have been sanctioned.

The Kremlin rejects the U.S. version of events. Moscow insists that the lawyer died of “heart failure” and that, instead of being a whistleblower, he was the real tax cheat. A Russian court even put Magnitsky on trial posthumously and found him guilty in 2013. It marked the first time in Russian history that a corpse was successfully prosecuted.

Since the passage of the Magnitsky Act, Moscow has also taken a raft of retaliatory measures, including “counter-sanctions” against U.S. officials and the institution of a controversial ban on American adoption of Russian orphans. Indeed, before the Ukraine and Syria crises, the Magnitsky affair was arguably the biggest point of contention in U.S.-Russian relations.

Follow the money — and dead bodies

One reason why the Magnitsky affair has caused such an uproar in the Kremlin may owe to where the rubles have since turned up.

Much of the $230 million from the Klyuev Group heist has since been located and frozen in jurisdictions all over the world. “Magnitsky stumbled into more than he realized, and more than we realized even after the passage of the Magnitsky Act,” Daniel Fried, the former U.S. Coordinator for Sanctions Policy, told CNN.

The U.S. Attorney in New York charged Prevezon Holdings, a Cyprus-registered company owned by the son of an influential Russian official, with having purchased Manhattan real estate and opened U.S. bank accounts using some of the pilfered funds. That case was settled in May. In the settlement, Prevezon did not acknowledge any wrongdoing and the U.S. government agreed not to pursue the company in any further litigation tied to this case.

Another related asset forfeiture case is still ongoing in Switzerland where authorities have relied on evidence turned over by Alexander Perepilichny, a Russian expatriate who confessed to having been the principal money launderer for the Klyuev Group before he broke ties with it.

The evidence showed Credit Suisse bank accounts in Switzerland where some of the stolen money had been deposited. One of those Swiss accounts, in fact, belonged to Quartell Trading, which is Perepilichny’s company — or was before he dropped dead suddenly while jogging near his home in Surrey in November 2012.

At only 44 years-old and not known to have been in ill health, Perepilichny’s death was initially declared “unexplained” by British police until traces of gelsemium, a poisonous flower, were discovered in his stomach.

A state coroner’s inquest into the case began in Britain on June 5 and was upended when BuzzFeed reported a week later that the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the body that oversees all U.S. spy agencies, concluded with “high confidence” that Perepilichnyy was killed on orders by Vladimir Putin.

Citing more than a dozen past and present intelligence officials in the U.S., UK and France, BuzzFeed alleged that the British government was suppressing crucial evidence. BuzzFeed said that the British government refused to comment on the report.

More recently, in late March 2016, a lawyer for Magnitsky’s family nearly died when he fell from the fourth floor of his apartment building, a day before he was due to submit new evidence to a Moscow court.

A dubious transaction

A signed contract dated December 18, 2007 — just days before the Klyuev Group’s fraudulent $230 million refund was processed — show that Perepilichny’s Quartell Trading agreed to buy $3,172,000 worth of high-end “furniture” from Balec Ventures, Issa al-Zeydi’s company.

A copy of a SWIFT transaction also obtained by CNN show that $900,000 of that amount was wired from Quartell Trading to Balec a few weeks later, on January 25, 2008.

It is unclear whether any of the vaguely described items of furniture was ever delivered to the listed address, a warehouse in Kharkiv, Ukraine.

Balec’s bank, the Federal Bank of the Middle East (FBME), approved the transaction for filing five days later, on January 30, 2008. Notably, the bank also stamped the document “checked for money laundering purposes.”

Less than a month later, according to the U.S. Justice Department, Quartell received nearly 2 million euro from a Latvian bank account that had received some of the stolen $230 million.

FBME, which was based in Tanzania, could not be reached for comment for this story. In May, the institution was shut down by Tanzania’s central bank because of U.S. accusations that it was “used by its customers to facilitate money laundering, terrorist financing, transnational organized crime, fraud, sanctions evasions and other illicit activity internationally and through the US financial system,” according to the US Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.

There are oddities to Quartell-Balec transaction, say financial analysts consulted by CNN who have examined the contract and supporting documents.

For one thing, Balec is described by FBME as being commercially engaged in the “buying/selling [of] promissory notes” and the import and export of building materials such as ceramic and marble tiles, timber, steel coils and “furnitures” [sic].

But it has no public profile or corporate website on which to showcase its inventory.

Ties to Assad’s WMD?

The Syria-born Issa al-Zeydi does not have a conspicuous public profile in Russia, apart from a largely inactive social media page on VKontake, the Russian version of Facebook, which CNN has confirmed belongs to the man who owns Balec Ventures.

He graduated in 1964 from Bauman Moscow State Technical University, where he studied engineering.

According to corporate registration records in Russia, al-Zeydi is also the owner and/or CEO of several small companies with next to no capital.

One of these, Aldzhamal Interneshal, claims to work in “non-specialized wholesale trade,” “the production of petroleum products” and the “manufacture of industrial gases.”

Al-Zeydi was also the director of Enterprises Ltd. and Fruminenti Investments Ltd., two companies that the U.S. sanctioned in 2014 for their connection to the Scientific Studies and Research Center, Syria’s government agency responsible for developing and producing non-conventional weapons and ballistic missiles,” according to the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

It is unclear if any of the $900,000 that Quartell wired to Balec went to support the Center.

Following the sarin attack in Syria in April, which prompted President Donald Trump to authorize US airstrikes against a Syrian airbase, the Treasury Department further sanctioned 271 employees of the Scientific Studies and Research Center, describing it as “one of the largest sanctions actions in its history.”

Repeated attempts to contact Issa al-Zeydi in Moscow for this story, using the registered addresses of his Russian-based companies and phone numbers, proved unsuccessful.

Additional reporting by Tim Lister and Mary Ilyushina in Moscow.