Story highlights

PM's party in the lead in Dutch broadcaster's according to preliminary results

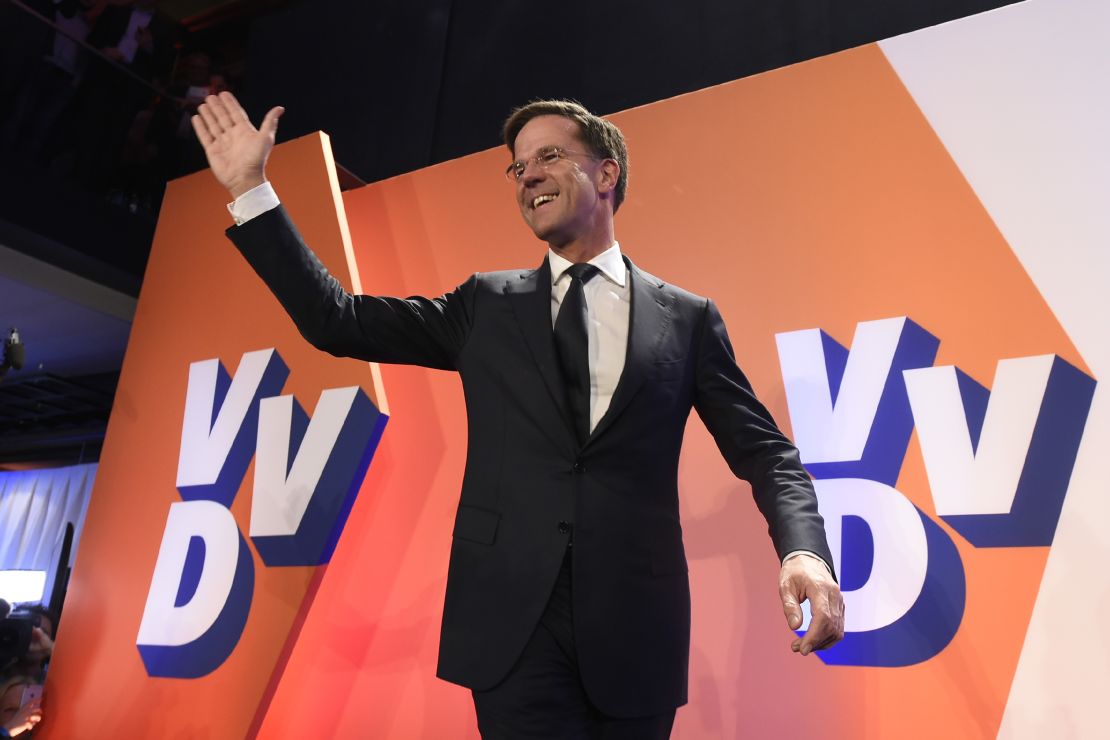

'This is a night for the Netherlands,' Rutte says

Conservative Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte has staved off a challenge from his far-right rival in an election widely seen as an indicator of populist sentiment in Europe, preliminary results indicated Wednesday.

The anti-immigrant firebrand Geert Wilders, who had promised to “de-Islamise” the Netherlands, was on course for a poorer than expected performance.

With more than half the votes counted, preliminary results showed Wilders tied for second place with two other parties, the mainstream Christian Democratic Appeal and D66. Rutte’s VVD party is projected to win 32 seats out of a total of 150.

The left-wing environmentalist GroenLinks (Green Left) party also appears likely to make big gains, while the PVDA (Labour) party, Rutte’s outgoing partners in a coalition, were on course for a historic defeat.

Turnout was 81%, a NOS exit poll said, the highest for three decades.

Wilders tweeted: “PVV voters thanks. We won seats, first victory is in. Rutte hasn’t got rid of me yet.”

“This is a night for the Netherlands,” Rutte told crowds of supporters after the exit polls were released. “After Brexit, after the US election, we said ‘stop it, stop it’ to the wrong kind of populism.”

Relief in Europe

The vote was the first of three elections this year in Europe in which populist, right-wing candidates were hoping for mainstream electoral breakthroughs. In April’s French presidential election, National Front leader Marine le Pen is expected to make it to the runoff vote. In German elections in September the euroskeptic, anti-immigrant Alternative für Deutschland party is expected win its first seats in the federal parliament.

There was relief in mainstream European governments at the Dutch result. “Large majority of Dutch voters have rejected anti-European populists. That’s good news,” the German Foreign Ministry tweeted.

Italian Foreign Minister Paolo Gentilioni tweeted his approval: “The anti-EU right has lost the election in the Netherlands. All together for change and revive the (European) Union.”

“Congratulations to the Dutch for preventing the rise of the far right,” French Foreign Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault said on Twitter.

The Dutch Labour party leader, Deputy Prime Minister Lodewijk Asscher, acknowledged its poor performance. “Today we share sadness,” he said, addressing a large crowd. “Sadness about a disappointing dramatic result, but please never forget our ideals are worthwhile,” he said. “Social democracy will come back. We will start building today.”

Coalition talks will begin once the results are confirmed. Due to the Netherlands’ fractured political system, it could take weeks for a new government to emerge.

Test of populism

The vote was widely seen as a test of populism in the wake of US President Donald Trump’s victory and the Brexit referendum vote in the UK.

Controversial anti-immigrant, anti-European Union figure Wilders had run on a “de-Islamification” platform, calling for Islamic schools to be closed and the Quran and burqa to be banned.

That message struck a chord with many ordinary Dutch voters who have been hard hit by the government’s austerity measures, and who feel the country has taken in too many refugees and migrants.

“The Netherlands is full,” Wilders supporter Jack told CNN outside a polling station in Volendam on Wednesday. “If it were up to me I would have stopped all [Turkish people] at the border.”

Others were disturbed by the tone of the campaign, and said they had voted tactically, to keep the far right out of power, or for parties they trusted to fight for causes they cared about, irrespective of the current political climate.

“I thought it was important and so I voted strategically,” said Amsterdam resident Kathie Somerwil. “I usually vote a little more left of center but at least now with this Wilders, I think this is not the Dutch way … so I voted VVD for Mr. Rutte.”

Author Bert Nap said he had voted for the progressive PVDA party because it had had the guts to go into government with Rutte’s party, despite that making it “very unpopular” with many supporters.

“I want to sustain a party in our political system that has acted very strongly … They will be decimated in this election but they have to be able to come upright for the next election and so you have to sustain it,” he said.

Complex political system

The splintered political landscape in the Netherlands – there were 28 parties on the ballot – and the country’s system of proportional representation mean coalition government is the norm.

But it can also lead to lengthy periods of political instability and uncertainty. The average time taken to form a coalition cabinet in the post-war era has been 89.5 days, according to the House of Representatives website. In 1977, it took 208 days for Dries Van Agt’s Christian Democrats to reach a power-sharing deal.

Voters say they are expecting a protracted period of talks before the make-up of the next government becomes clear.

“I think there will be a lot of negotiations,” said research analyst Robin Vanstraalen. “Given the whole fragmentation and the polls showing it will be a long process. And eventually it will end up in the middle – which is where we have been for the last few years already.”

Factors that boosted support for leader

At one stage, Wilders and Rutte were neck-and-neck in the Peilingwijzer poll of polls by Leiden University, but in recent days Rutte had taken the lead. He had moved to the right in response to Wilders’ popularity.

Andre Krouwel, political scientist at the Free University Amsterdam, and owner of election website Kieskompas, said Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s ongoing war of words with the Dutch government appeared to have boosted support for Rutte.

Tensions between the Netherlands and Turkey have been high since the Dutch government refused to allow Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu to visit Rotterdam for a political rally last weekend; Erdogan retaliated by blaming the Netherlands for the Srebrenica massacre in 995.

Voter turnout in the Netherlands is traditionally high. A CNN reporter in The Hague State saw long queues forming at polling booths in the city’s central station as commuters returned home from work.

Amsterdam polling station volunteer Hanneke Spijker told CNN large numbers of people had been coming out to vote since early Wednesday morning. “It’s incredible,” she said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if it will be a record turnout … there were lines, and we never have lines.”

CNN’s Rosalyn Saab and Hilary McGann contributed to this report.