Story highlights

A South African app allows volunteers to remotely assist blind people

Over 10,000 people from 50 countries have signed up

The algorithm connects people of the same culture and age

Two years ago South African Chris Venter lost his eyesight from a virus he contracted while travelling.

A former chef, he was determined to keep cooking. To do so, he’s had to relearn how to navigate a kitchen and even how to chop onions. If he wants to pour milk, he has a device that beeps when the glass is nearly full.

But there are still obstacles, like seeing the color of the onion, or the milk’s expiration date.

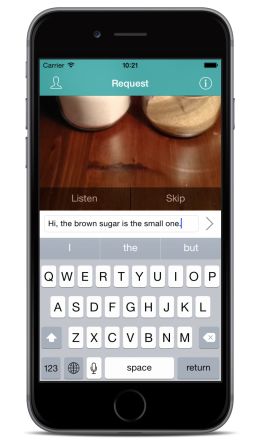

Enter a new app, BeSpecular, which connects Venter to volunteers around the world who want to lend their eyes to the blind.

“The first time I used it I was about to chop an onion and I was uncertain if it was a white or red onion that I’d taken, so I snapped a picture,” the 43-year-old blogger said.

Once the request is submitted, a handful of volunteers, or so-called “sightlings”, receive a notification on their smartphones.

“It took me about 30 seconds before I had the first response,” Venter adds.

Blindness around the world

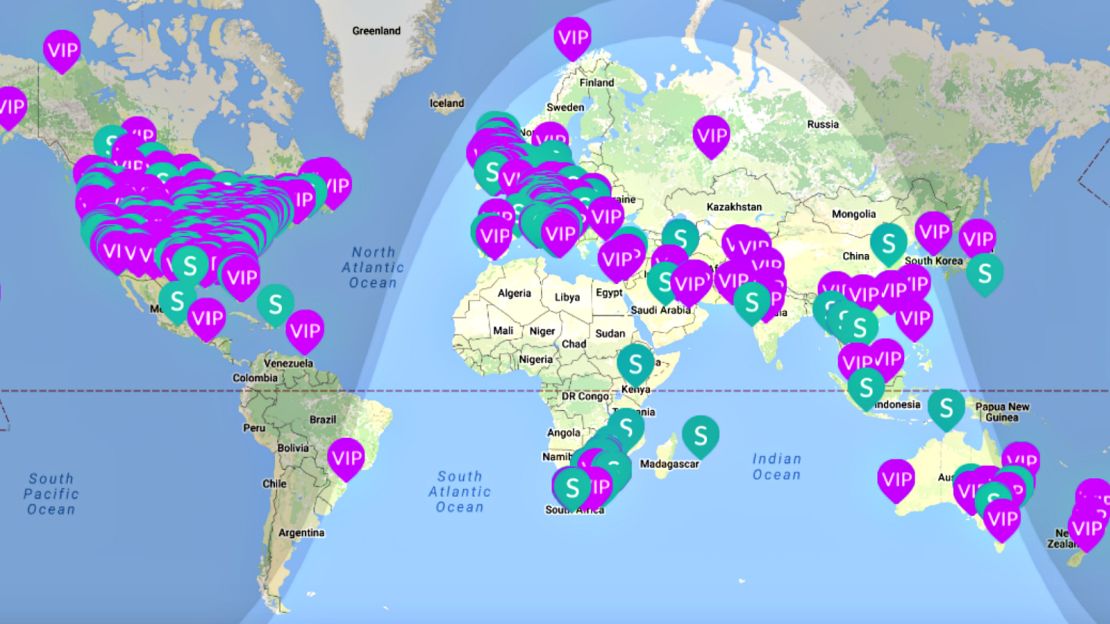

The app launched on World Sight Day on October 13, 2016, and so far has around 10,000 subscribers, with a roughly equal split between the visually impaired and volunteers, according to the company, based in Johannesburg, South Africa.

The idea for the app was conceived at Stanford University in 2014, where CEO Stephanie Cowper and CTO Giacomo Parmeggiani were classmates.

“We wanted to have a big impact on people’s lives using tech,” Cowper says.

“The disability industry was somewhere we could actually make a big difference.”

Can this smartphone app help the blind to see again?

Similar to dating apps

The app uses an algorithm to connect the right people, much like a dating app.

The requests go out to volunteers of similar age and physical location to the visually impaired, Cowper explains.

“Things are very culturally specific in terms of brands.”

Take Twinings Tea or the popular English spread Marmite, for example. “Even if someone shows you the back of the pack or jar, you would probably still recognize what it was,” she said.

Sending the request to more than one person puts less pressure on the volunteers, Cowper says.

“If you’re busy, you don’t have to worry.”

How to use a smartphone when you can’t see

Like others with visual impairment, Venter navigates his smartphone using a touch-based interface and synthetic speech.

“My screen just looks blank. As I slide my finger around the touch screen, whatever I’m hovering over will be read to me, so I can just double-tap it to open it up.”

BeSpecular isn’t the only app helping the visually impaired. Another uses algorithms to identify what’s in the picture, such as mobile camera application TapTapSee, which automatically identifies objects. Others, such as the Danish app Be My Eyes lets users interact directly through a live video feed.

Chris Danielsen, a director at the National Federation of the Blind in the U.S., says while these apps can be very useful, there are some caveats to consider.

The privacy of the blind user is one example. “You want to be careful when you’re sharing information with a third party that you don’t know. As a blind person I tend to be very careful with anything of a personal nature.”

Can an app replace human contact?

Then there is the question of whether an app can replace human contact.

Danielsen says the apps are likely to be an additional service to friends or already available human assistance, which is still his preference when going shopping, for example.

“It’s always better to have somebody who knows you and who knows how to work with you,” added Danielsen.

From Japan to Finland to Mexico, BeSpecular has users in over 50 countries worldwide, according to the company.

Next up for BeSpecular is translating the app into other languages and launching a business software – currently being tested by a number of companies in South Africa – that aims to raise awareness of disability in the workplace in Africa, where there is still social stigma around blindness, Cowper says.

“We are hoping to break down those barriers and get people talking.”