From all corners of a nation they come, often walking for hundreds of miles barefoot: Ethiopian Orthodox Christians on a once-in-a-lifetime journey.

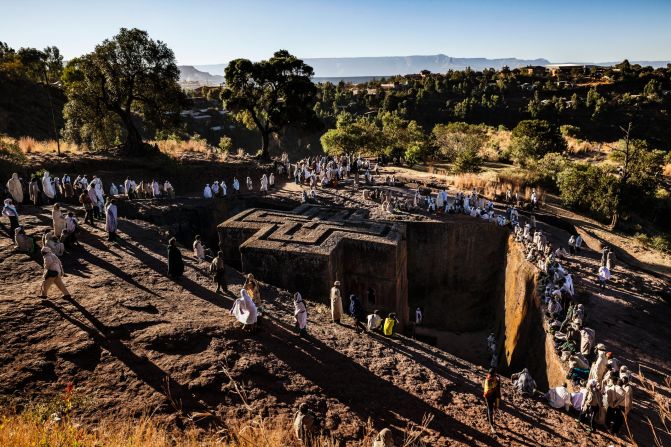

Their destination is Lalibela in the north of Ethiopia. A town of approximately 20,000 people, Lalibela’s population swells five-fold in the first days of January, pilgrims converging to celebrate Genna (or Ledet) – Christmas according to the Ethiopian calendar.

What they’re here for is to take a path from darkness into the light; through 800 years of history and enter a “New Jerusalem” – tangible, permanent and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

But most of all, they’re here for God.

Step into the ‘New Jerusalem’

In the 12th century AD King Lalibela, Ethiopian leader and Christian, ordered the building of a second Jerusalem when the original was captured by Muslims in 1187 AD. The result was 11 interconnected churches, carved into the mountain by hand. But unusually, Lalibela’s churches were dug straight into the ground. Hewn out of solid rock, perhaps best known is the Church of St George, shaped in a Greek Orthodox cross.

Nearly impossible to see at a distance, the impressive feat – completed in 23 years – provided a safe space for Christians to pray, hidden from Muslims invading from the North.

A concealed treasure in the Horn of Africa, photographer Tariq Zaidi deployed his camera as he followed the pilgrim route in and around Lalibela earlier this year.

“I’m astonished that everybody doesn’t know about this place,” he says, remembering that among the throng there were perhaps 100 foreigners. “It’s a gem that is hidden at this point in time.”

He recalls the majesty of the architecture and beauty of the region, but most of all its people.

“They’re very poor, very humble,” he says. “They come for the pilgrimage hopefully once in their life if they can afford it. Many people have walked across the country, with almost nothing with them.”

In the lead up to Genna, pilgrims, both men and women, sleep out on plastic sheets in a particular area of the town.

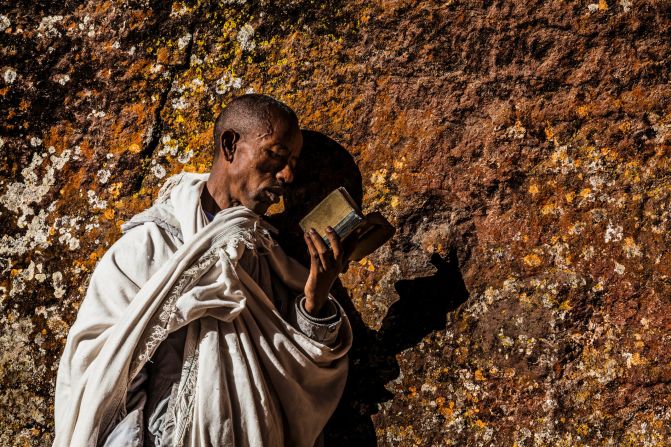

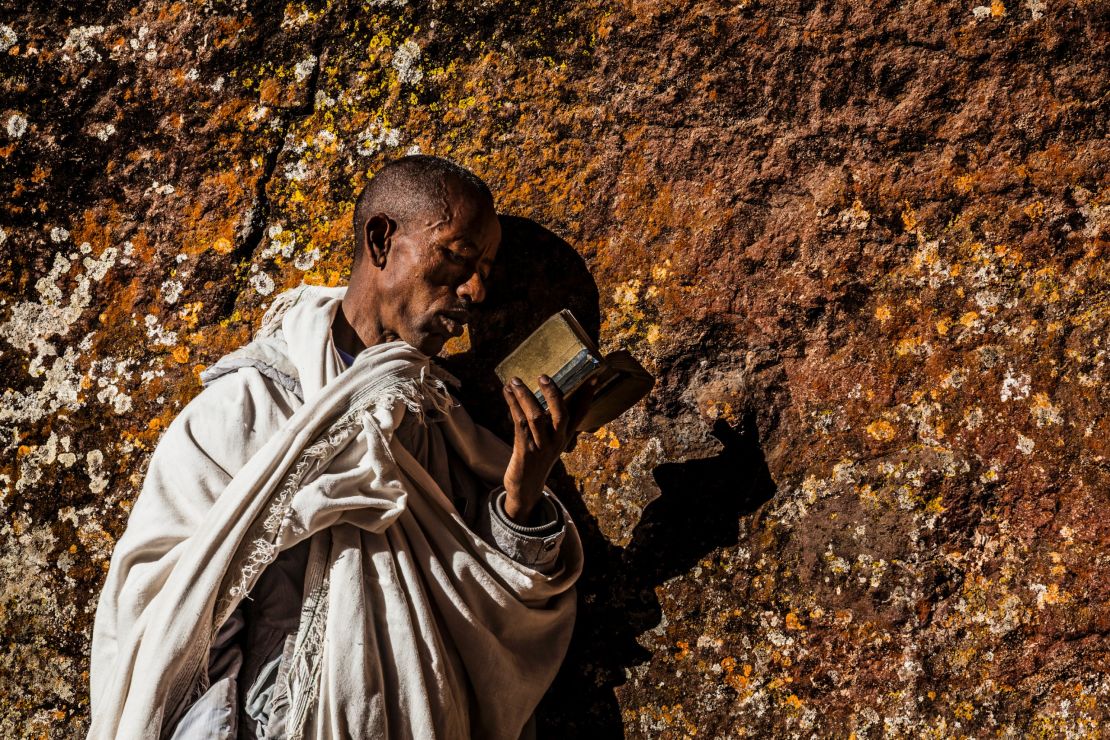

“Thousands of people are just lying there,” says Zaidi. “[But] it’s not like a refugee camp; there’s an amazing atmosphere. They are singing and dancing, reading their bibles and prayer books. They’re so happy – ecstatic – to be there and be part of this unique celebration.”

Zaidi describes the local community coming out to help pilgrims, feeding them and even help wash weary feet. When the sun goes down, thousands of candles are lit and the praying continues.

“It’s very beautiful, poetic – even romantic – in a way very few things in our world are,” says Zaidi. “They all support each other.”

‘I was moved to tears’

The activities of Genna eve begin at five in the morning. Pilgrims, dressed in white, make their way to the 13 churches, navigating between them using interconnected tunnels 40 feet beneath the ground.

There’s symbolism at play, explains the photographer: “There’s one particular passage in the network that is very long. I’ve got no idea how long it is – I’d guess 300 meters – and it’s pitch black.

“There’s only one way in and one way out. There’s no turning back, and when you come out you come out literally at the door of the church. I was told that this corridor, like many others, was experiencing darkness going into the light – coming out into Heaven, effectively.”

Mixing with the pilgrims and priests – who stay in each church and are the only people to wear color – Zaidi says the experience was “like going back in time;” a place and tradition untouched by modernity.

“In some of the ceremonies you’re standing in a 12 inch by 12 inch space,” he recalls. “You can’t move in any direction. You’re there until it ends – even if you pass out you’re not going to fall.”

When nightfall comes pilgrims pray en masse by the light of candles and the stars. Most continue to celebrate through until daybreak.

“That night was one of the most magical things I’ve ever seen in my life,” Zaidi says. “I’m not a religious person at all… but I was moved to tears by watching these ceremonies.”

The following day the pilgrims filter out of the town, and Lalibela contracts once more. Until next year, it will remain a relatively little-known heritage site. However the memory remains.

“If you want to be moved by mankind, moved by religion, go there,” implores the photographer. “If you’re not moved to tears by the devotion, spirituality and kindness of these people, nothing will move you. It truly is a remarkable experience.”