CNN Films’ documentary “Unseen Enemy” is now available on CNNgo.

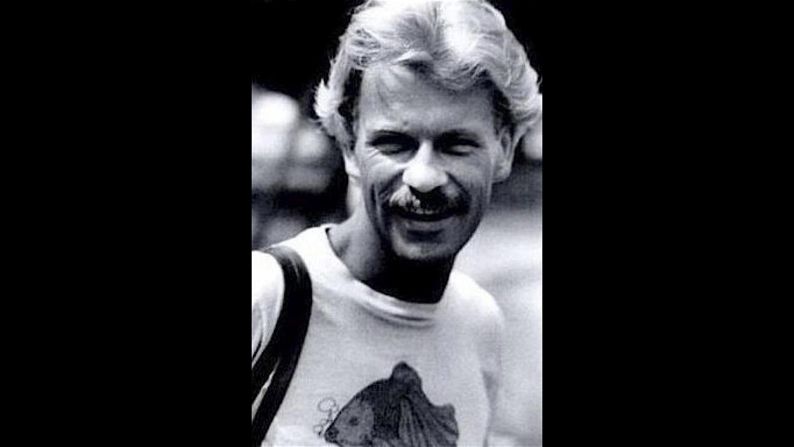

When a researcher’s scrawling of the letter O was misinterpreted as a zero in reference to a HIV patient in the early 1980s, the provocative term “patient zero” was born.

It triggered a wave of events in which the patient, Gaëtan Dugas, a French-Canadian flight attendant, was erroneously blamed for bringing the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, to the United States.

Decades passed before research, published in the journal Nature last month, cleared Dugas’ name and provided strong evidence that the virus emerged in the United States from a pre-existing Caribbean epidemic in or around 1970.

Though Dugas’ disturbing saga has been put to rest, the term “patient zero” lives on,and continues to create confusion and curiosity about how disease spreads.

“Zero is a capacious word,” Richard McKay, a historian at the University of Cambridge in England and a co-author of the Nature study, said last month. “It could mean nothing, but it can also mean the absolute beginning.”

Super-spreaders vs. super-shedders

“Patient zero” is still frequently used to describe index cases – the first documented cases of a disease observed or reported to health officials.

Many scientists and public health officials are loath to identify those patients and avoid the term “patient zero” altogether, said Thomas Friedrich, an associate professor of pathobiological sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine.

“Identifying one person as the patient zero, on the one hand may give an incorrect impression about how the disease emerges in the first place and, on the other hand, insinuate that somebody should be blamed for this outbreak, when that’s not really appropriate,” Friedrich said. “Nonetheless, it’s important scientifically and for people and public health to understand index cases so that we know how diseases are coming into a community and how to stop their spread.”

Some scientists argue that it’s equally important to analyze primary cases – the person or animal that first brings a bacterium or virus into a population. For many infectious-disease pandemics, the primary case will never be known, said Dr. Ian Lipkin, a professor of epidemiology and director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University in New York.

“It is not uncommon for infectious agents to percolate in the environment for years or even decades without detection,” Lipkin said, adding that an agent could enter the human population in more than just one person.

And even after an infectious agent crosses into the human population, some people are more capable of spreading it than others, he noted.

“So it may make more sense to talk in terms of super-spreaders than patient zeroes,” Lipkin said. “Super-spreaders may travel or engage in certain types of behaviors … that result in transmission to large numbers of people.”

For instance, even though Dugas wasn’t the patient zero of HIV, he still may have served as a super-spreader, Lipkin said.

Still others might be super-shedders, individuals who shed many more types of the virus into the environment – and not just through person-to-person contact – than others.

Whether they were truly patient zero, super-spreaders or super-shedders, here are the stories of six people who may have played a role in the spread of deadly diseases in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The real Typhoid Mary

One of the first-known examples of super-spreading, and maybe even super-shedding, was Mary Mallon.

She became known as Typhoid Mary, said Dr. Richard Stein, a research scientist at New York University School of Medicine and adjunct assistant professor at City University of New York, who wrote the book “Super-Spreading in Infectious Diseases.”

“I’m still not sure whether she was only a super-spreader or whether she was also a super-shedder or possibly both,” Stein said.

Mallon, an Irish-born cook, appeared healthy as she prepared meals for the families she worked for in the early 1900s in New York. Soon after her meals were served, members of the households where she worked developed typhoid fever, a life-threatening illness caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi.

As more households where she worked developed typhoid fever, Mallon was soon identified as something of a patient zero, even though she never developed the symptoms.

“There are these individuals, like so-called Typhoid Mary, who for one reason or another may be infected with a pathogen and not have that many symptoms but can shed that pathogen in a way that makes it infectious to other people,” Friedrich said.

Mallon was forced into quarantine on two occasions for a total of 26 years, during which she unsuccessfully sued the New York department of health, saying she didn’t feel sick and therefore could not infect other people. She died in 1938.

No one really knows whether Mallon was the true patient zero in the typhoid case or simply a super-spreader or super-shedder. After all, naming a patient zero remains tricky.

“I can’t even think of a time when we’ve actually known an index case,” said Dr. Bertram Jacobs, director and professor of virology at Arizona State University’s School of Life Sciences. The closest we can come is probably the SARS epidemic, he said.

The spread of SARS

Scientists have traced a serious super-spreading event during the 2003 global outbreak of SARS to one doctor and one night that he spent in a Hong Kong hotel, according to a World Health Organization bulletin (PDF).

Dr. Liu Jianlun, a 64-year-old medical doctor from southern China’s Guangdong province, was ill during his stay at the hotel and may have transferred the virus to at least 16 other guests staying on the same floor, according to the bulletin. Coincidentally, Liu stayed in room 911 on the ninth floor of the Metropole Hotel.

“You wouldn’t call him ‘patient zero,’ but if you consider his impact in terms of the outbreak, he was critical in the spread of the disease,” said Lipkin, who received the International Science and Technology Cooperation Award this year for assisting the WHO and the People’s Republic of China during the height of the SARS outbreak.

The other hotel guests who were exposed to the virus probably traveled to other countries after being infected. In less than four months, about 4,000 cases and 550 deaths from SARS could be traced to Liu’s stay in Hong Kong.

How was Liu infected with SARS to begin with? The hospital where he worked treated SARS, and Liu might have come into contact with the virus through a patient.

In Guangdong, it was believed that a farmer first developed SARS after coming in contact with the virus through an animal. Such diseases that are spread from animals are called zoonotic.

“For many zoonotic infectious diseases, the first step involves the species jump, and then if the virus is able to be transmitted directly among humans and no longer needs the animal reservoir for this, it has the potential to unleash an epidemic,” Stein said. “I think that, exploring this from a global perspective, that very first patient would be patient zero.”

‘Contagion’ in real life

SARS is believed to have originated in bat species and then spread to other animals, such as civet cats, before infecting humans in China, according to the WHO.

“In the process of adapting from one species to the next, you have the spread of disease,” Lipkin said, who served as senior technical adviser during the production of the 2011 medical thriller “Contagion.” Some of the scenes in the film mirror his memories of Beijing when he assisted in managing the SARS outbreak, Lipkin said. In the film, a fictional deadly virus sweeps the world after migrating from a dead pig to a chef that handles it.

About 60% of all existing human infectious diseases are zoonotic, said Stein, the research scientist at New York University. In other words, there are numerous microorganisms in nature that infect animals – and some of these same microorganisms infect humans.

“It was predicted that by 2020, about 10 to 40 new viruses might emerge in humans,” Stein said, citing a 2008 study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“There are plenty of potential patient zeroes out there that get infected with stuff,” said University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Friedrich.

“What’s preventing a new pandemic is not so much that animal viruses just can not infect humans. In fact, the more we look, the more we see that people do get infected with animal viruses all the time,” he said.

The key to an outbreak, Friedrich said, is for those viruses to be transmitted from a single person to more people. That’s exactly what H5N1 avian flu, or bird flu, did.

A new virus emerges

In 2004, a 6-year-old boy named Captain Boonmanuch became the first confirmed casualty of bird flu in Thailand as the virus spread across Asia, USA Today reported. Captain might not have been patient zero, but his family recalled that before falling ill, the youngster scooped up a squawking chicken and carried it to his uncle’s home.

It is believed that the chicken shed the avian flu virus during this encounter, possibly infecting Captain and others.

Between 2003 and 2016, a total of 856 cases of human infections with H5N1 viruses worldwide have been documented, and there have been 452 deaths, according to the WHO (PDF).

“New epidemics that emerge in humans often come from contact with animal diseases,” Jacobs said. “The viruses that really circulate in humans turn out mostly to be reassortants between viruses, usually from birds and other human viruses.”

A reassortantis the virus that emerges when the genetic material from two or more other viruses infecting a single human or animal host mix together. That mixing is often referred to as areassortment event, which occurs frequently in nature.

“Avian influenza viruses don’t replicate well in humans, human influenza viruses don’t replicate well in birds, but if a bird virus and a human virus gets into a pig, you can have reassortment and get totally new strains out,” Jacobs said.

That’s what happened in 2009 with another type of flu – H1N1 swine flu – that took the world by storm.

A boy who survived swine flu

H1N1 influenza emerged in humans to cause a pandemic in 1918, Friedrich said, and then a similar pandemic hit the world in 2009.

It is believed that, leading up to the 2009 pandemic, pigs became infected with a few different viruses. A reassortment resulted in an H1N1 strain that had some eerie genetic resemblances to the 1918 virus, Friedrich said.

The resulting outbreak serves as an example of how new flu viruses might enter the human population, Friedrich said.

“For the most recent H1N1, it definitely seems like it came from pigs, (even though) they’re ultimately bird viruses,” Friedrich said.

“The term that people use in the flu world is that pigs are ‘mixing vessels,’ in which bird viruses and mammal viruses can mix together and create new combinations that are more likely to infect people than just straight-up bird viruses,” Friedrich explained.

Edgar Hernandez was a 5-year-old living in the Mexican town of La Gloria when doctors identified him as the earliest documented case of swine flu in the 2009 outbreak. Edgar survived the illness, which his mother believed developed due to a pig in the neighborhood.

“With these index cases, it’s not just getting infected with an animal virus, but rather, that virus probably has to do things to become transmissible in people, and it has to get out of that first person and get into other people to really become an outbreak,” Friedrich said. “Some viruses can do that, and some can’t. Some can do it but only weakly, and they die out, and some do it really well, and then those become the outbreaks that we hear about.”

Emile and Ebola

One virus long known to aggressively pass from human to human, like a piton in a dangerous race, is Ebola.

Ebola can be introduced into the human population through close contact with the blood, secretions, organs and other bodily fluids of infected animals, such as fruit bats, monkeys or even forest antelope, according to the WHO.

A 2-year-old boy was the suspected first case of the recent Ebola outbreak, suggesting that there was a “single introduction of the virus into the human population,” according to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2014.

Emile Ouamouno was a toddler living in the southern Guinea village of Meliandou when he suddenly developed fever, vomiting and severe diarrhea in December 2013. Officials said he might have contracted the disease from a bat.

He died four days after his symptoms emerged. Within a month, his grandmother, mother and 3-year-old sister died from the disease as well.

As in previous Ebola outbreaks, the virus continued to spread through contact with the body and with human bodily fluids, possibly even after the human died, said Stein, the research scientist at New York University.

“Ebola is interesting, because for this infectious disease, studies found that unsafe burial practices, which involve washing and preparing the body of the deceased, apparently contributed to the infection of many people who were participating in this cultural practice,” Stein said, noting that people could have dispersed a high number of viruses before dying, as well.

‘In the wrong place at the wrong time’

MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome, is a fierce virus identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and named in 2013.

Though scientists are still studying the origins of the virus, they know that camels were likely to be an animal source of MERS infection in humans, according to the WHO, which has been notified of at least 1,813 cases of MERS infections since 2012.

Last year, there was a MERS outbreak in South Korea, and a 68-year-old man with an extensive travel history was reported to be the so-called patient zero.

The man traveled to Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Qatar before returning to South Korea. He was not ill with symptoms during his travels, according to the WHO, but once he fell ill, he went to the Samsung Medical Center in Seoul. According to the the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the time between being exposed to MERS and experiencing symptoms can range from two to 14 days.

The man may have transmitted MERS to 28 other people before arriving at the hospital, according to a study published in The Lancet in July. A patient among them who subsequently sought care may have transmitted MERS to an additional 82 people in the hospital.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

However, it’s still important to keep in mind that “it’s very difficult for us to identify who is a cardinal case in an outbreak,” said Lipkin, the epidemiologist at Columbia University. “There are rare examples of when we do see that happen, like in the Ebola outbreak, because we followed it in real time, but when you try to reconstruct after the fact, it’s easy to be misled.”

And being misled isn’t good for science or humanity, said Jacobs, the virologist at Arizona State University.

“As humans, we sort of want to make tight stories about things, and sometimes that involves blaming or saying, ‘Oh, this person started the epidemic,’ ” Jacobs said. “With history, at least the history of infectious diseases, it’s not that tight. It’s not that clean.

It’s very rare that we can say, ‘This person did it; this person started it.’ Even if they did, most of the time, they weren’t doing anything consciously to start an epidemic. They happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.”