Story highlights

CDC identifies a fourth US patient, a Connecticut child, with a bacteria resistant to the antibiotic of last resort

CDC says it anticipates this bug will be identified with increasing frequency

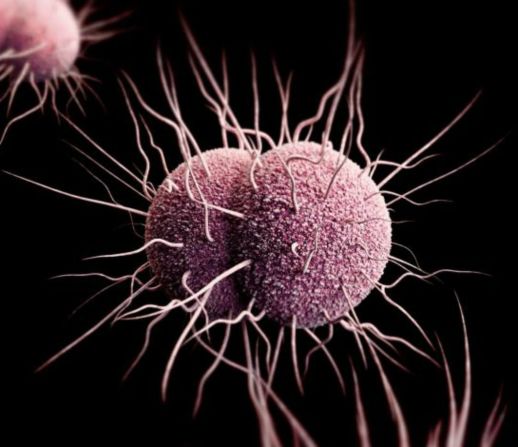

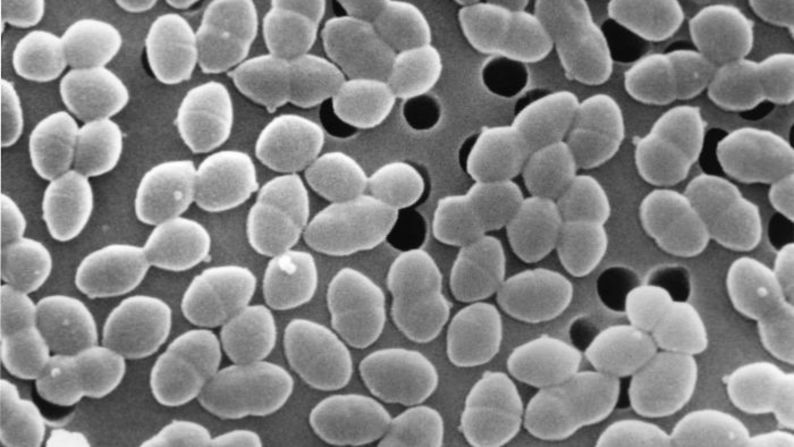

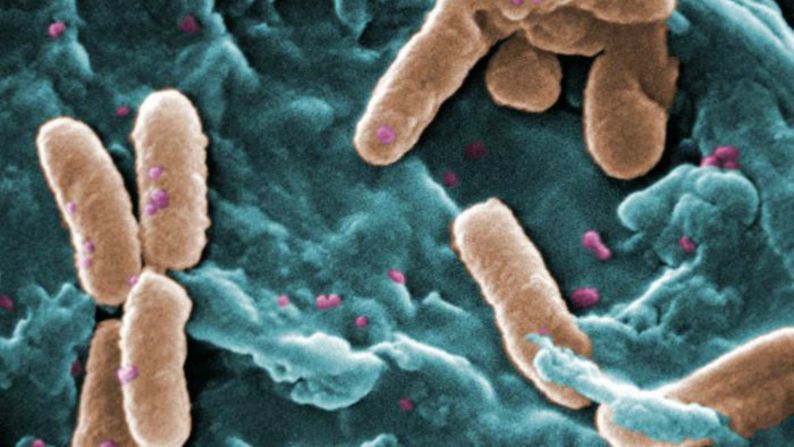

Health officials have detected a potentially deadly superbug in a fourth US patient, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced today. In July, scientists identified a strain of Escherichia coli that the antibiotic of last resort cannot treat in a Connecticut pediatric patient.

The girl had traveled to the Caribbean and developed fever and bloody diarrhea on June 12, two days before returning to the US. During the illness, the child made outpatient visits to a clinic and once to an emergency room, but did not require hospitalization.

“She had traveler’s diarrhea, probably a parasitic infection, given some of the symptoms, and per normal clinical procedures, they did a stool culture,” explained Maroya Spalding Walters, CDC epidemiologist and a co-author of the report. One of the organisms they detected during this stool culture was E. coli containing the mcr-1 gene, which causes resistance to a class of antibiotic drugs known as polymyxins. That class of drugs includes colistin, the medicine doctors use when an infection does not respond to other drugs.

Surprisingly, the E. coli containing the mcr-1 gene was non-pathogenic. It was another bacteria that caused the girl’s diarrhea, said Walters.

More cases anticipated

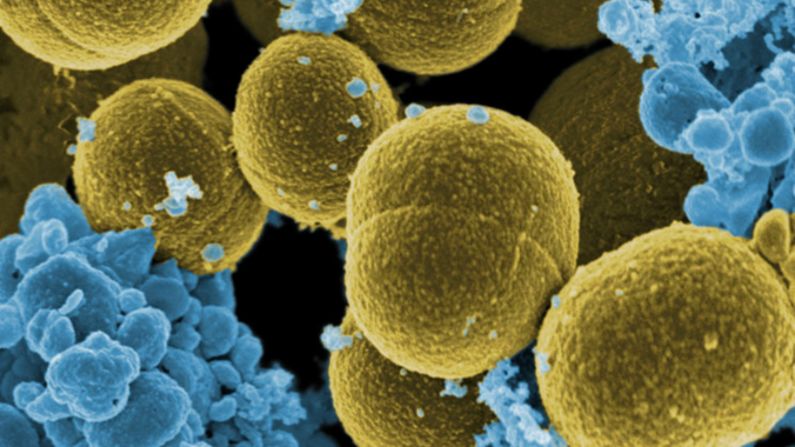

“Travelers often can pick up these bugs and become ‘transiently colonized’ as we call it … and it’s no longer detected,” said Walters. She explained that a healthy person can become colonized with the mcr-1 bacteria without feeling sick. Immunocompromised patients might become sick, and healthy people could if the bacteria is introduced into their bloodstream from a cut, said Walters. Simply having the bacteria lingering among the many bacteria on the skin or in the gut does not automatically make a person ill.

No environmental contamination or transmission to other people has been detected, Walters and her co-authors noted in the report.

“As more surveillance systems with broader testing are established, it is anticipated that mcr-1 will be identified with increasing frequency,” wrote the authors of a related CDC report issued today.

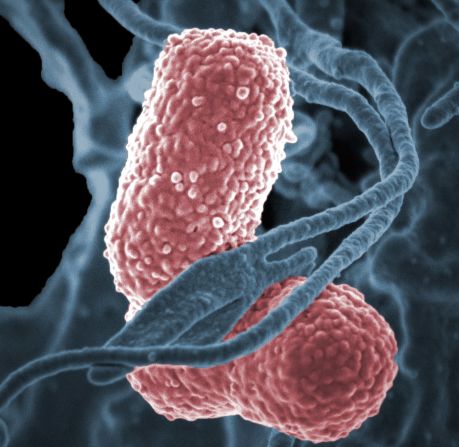

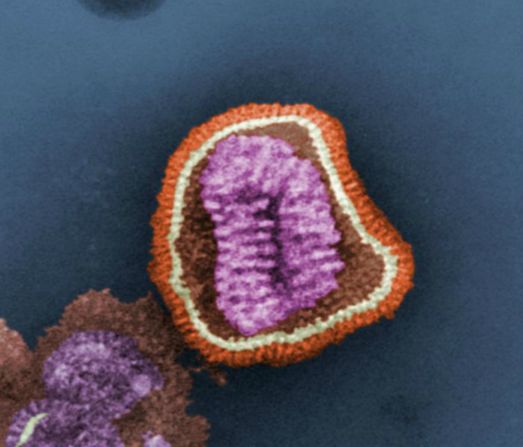

“What is key for mcr-1 is really that we’re doing the surveillance to monitor the spread because [it] is on this mobile piece of DNA so it can move between bacterial species,” said Walters.

If the gene is transferred to bacteria that are already resistant to most other antibiotics, the result would be a strain with a combined resistance to all antibiotic drugs available today – the ultimate superbug.

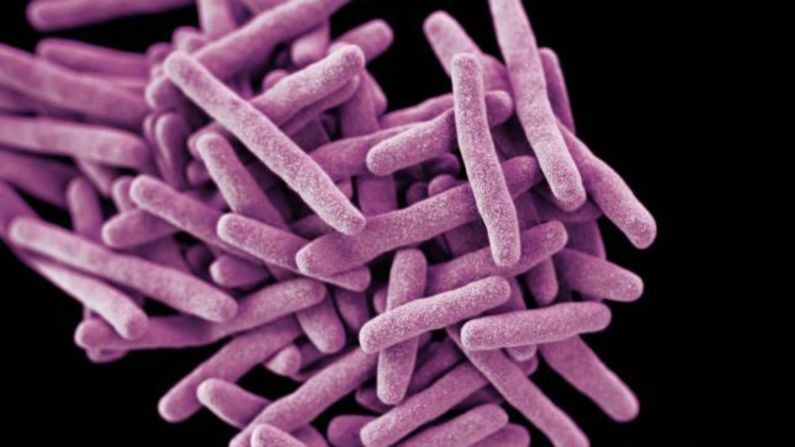

First reported in 2015, the mcr-1 gene was detected at that time in food, animal and patient samples from China. Since its discovery, the gene has been reported in Africa, Asia, Europe, South America and North America.

In the United States, mcr-1 has been identified in four patients with E. coli infections – one patient each in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and now Connecticut — and in two intestinal samples from pigs tested by the US Department of Agriculture.

Follow-up on a single patient

The related CDC report described the case investigation conducted for a female patient with mcr-1 in Pennsylvania. Scientists do not know how this woman came into contact with the resistant bug, since she had not recently traveled internationally, had not come into contact with livestock and had played only a small role in preparing meals with store-bought groceries.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Tracking her case, health authorities identified 20 people considered high risk contacts, including household members, and 98 people considered lower risk contacts. Of these, all 20 higher-risk contacts and 78 lower-risk contacts agreed to be screened. No one tested carried the mcr-1 gene. The CDC also tested samples from four medical facilities where she received healthcare services over the past year and detected no colistin-resistant organisms.

These findings suggest the risk for transmission from an infected patient to healthy people might be “relatively low,” said the CDC.