Story highlights

Diambars is Senegal's top football academy, co-founded by Patrick Vieira

Access to its stellar facilities and training is free, but highly competitive

The boys dream of playing pro football in Europe, but the school prioritizes studies

For 13-year-old Amar, it’s Real Madrid. For 17-year-old Junior, it’s Marseille.

Like so many boys, their dream is to travel from Africa to Europe and follow in the footsteps of footballing legends like Yaya Toure and Patrick Vieira.

But unlike most, and thanks to expert training, the boys at Senegal’s Diambars football academy have a fighting chance of realizing this ambition.

And if the dream doesn’t materialize – which it won’t for the majority – the teenagers are being schooled in the idea that success doesn’t just mean soccer glory.

“It’s possible that they won’t succeed in football, but they will in life,” Moussa Kamara, Diambars’ technical coaching director tells CNN.

“Diambars is above all about making men, men who otherwise wouldn’t have had a career, able to succeed in life, to have families, become heads of businesses, ministers, presidents and model men for emerging Senegal. It’s not just about football.”

Football for education

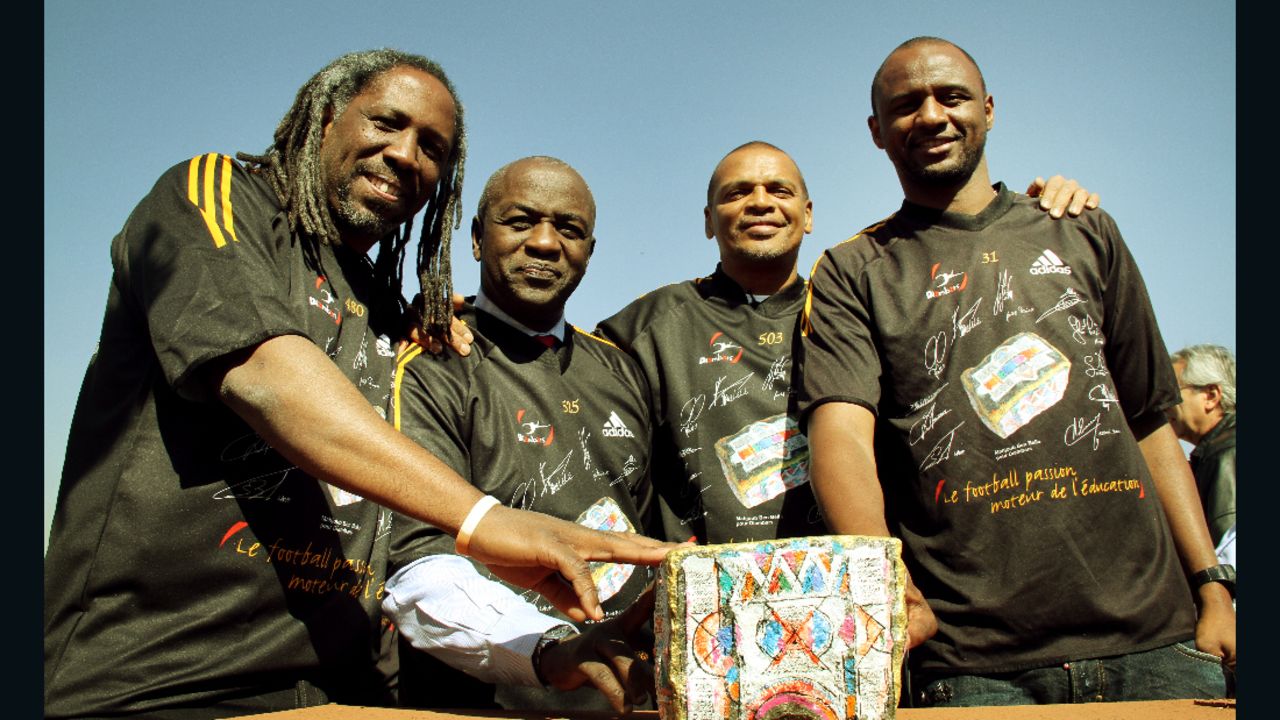

It’s a vision shared by the school’s four founders: to give back to society what football had given to them.

One was former Arsenal captain Patrick Vieira, who rose from humble roots in Senegal’s Dakar to win three English Premier League titles and four FA Cups. He also became a world and European champion with the France national team.

He was joined by French goalkeeper Bernard Lama (Lille, PSG) Beninese defender Jimmy Adjovi Boco (RC Lens) and Saer Seck, the President of Senegal’s football league.

Read: Inside China’s $185m football factory

The goal is to utilize the energy bursting from every sandy football pitch and pavement kickabout, turning it into a driver for education.

In Senegal, only 34% of boys and 27% of girls attend secondary school, according to UNICEF figures, and at 58% its literacy rate is among the lowest in Sub-Saharan Africa. For most, the pressure to earn a living, often through farming or fishing, crushes the luxury of choice.

Moustapha Fofana, 24, comes from a suburb of Dakar. His father earned a living selling eggs from the capital to the south, while his mother stayed at home to look after his brother and sisters.

“My mum and dad both ended their schooling very early,” he says. “There were times when it was very difficult – my family wasn’t well off. I didn’t pay much attention to my studies – I only wanted to play soccer.”

Now Moustapha’s outlook has radically changed.

After his footballing skills earned him a place at Diambars aged 13, his focus on school and soccer secured him a full scholarship to the University of Louisville in the U.S.

A freshman there since September, he’s still hopeful of a career in pro football – but studies are also central to his plans.

“My dream is to graduate here, and in the future to create a company to help my family have a better income,” he says. “And also to do something to help Diambars – it’s the least I can do.”

Train, study, dream: The Senegalese football school turning boys into men

Golden opportunity

For the lucky ones like Moustapha, the school is a life-changing opportunity.

Seventy kilometers south of Dakar – a drive that, thanks to endless speed bumps and traffic, takes three hours on the straight, tarmacked road – Diambars is a stone’s throw from Saly, Senegal’s beach holiday hub. French tourists flock there to relax on its white sands.

Just 10 minutes further is the country’s second city, Mbour, whose bustling port lures teenage boys away from school to schlep crates of bass, bream and tuna from brightly-painted boats to the pungent market above.

On a sandy road out of town, Diambars’ primrose-yellow gates lead to some of the best facilities in the country. Six football fields – one grass, five artificial – lie next to a turquoise swimming pool, the school building, gym and accommodation for around 90 students.

When the boys arrive, bright-eyed and full of ambition, most have only ever played football on sand.

“It’s a big change,” says head coach Moussa Kamara. “The ball rolls, rather than stopping in holes.”

The students, aged from 12 to 20, have access to on-site physiotherapists, a personal tutor and a raft of coaching staff. One of them used to train Senegal’s national team – “the Lions of Teranga” – alongside former French international Alain Giresse.

Lessons run from 8am until 1:30pm before lunch and rest time. By 5pm, when the baking Sub-Saharan sun has cooled, the teenagers hit the football pitches – dressed from head to toe in professional gear, thanks to the school’s sponsors.

They are remarkably polite: every time they file past their coaches, they shake their hands earnestly. The long wait for the school lunch, the national dish of rice and fish – theboudienne – is nothing like the disorderly mob familiar to most schools.

Studies first, football second

For their families, this stellar education costs nothing. The $1.7 million start-up costs of Diambars, seen as the premier of hundreds of smaller football schools in Senegal, were funded in large part by private donation from Mr Seck. The president of the country’s football league made his fortunes in the French fishing industry after an injury ended his playing career early.

“The boys know that academics are very, very important,” Seck tells CNN. “A country like Senegal is not being developed by football. It will be developed by having well-prepared boys to invest and manage, to be doctors and engineers. Diambars will be a part of that.”

That’s why the focus here is on passing exams more than passing the ball. If a student doesn’t work hard in the classroom, he won’t go out on the pitch.

It’s tough, but it works – nearly 100% of students achieve the brevet (ninth Grade diploma,) according to the school, and roughly 80% achieve the Baccalaureate, the equivalent of SATs. That’s double the national average for 2013, the most recent year for which records are available, when only 39% of 60,000 pupils enrolled passed the exam.

Unsurprisingly, competition for a spot at the school, with its cool classrooms and manicured grounds, is fierce.

The boys are selected on their football abilities alone, with the help of over 40 regional trainers across Senegal. They must get through five stages of technical tests, starting at their local football schools.

Getting a place at Diambars, whose name means warriors in local language Wolof, is almost as unlikely as Leicester City winning the Premier League – for only 16 places, 3,000 to 5,000 boys try out each year. For many, getting in is “a dream come true,” says director of studies Amadou Tamberou.

“We’ve recruited children who were on the streets, Talibes (child beggars) who have today got their Baccalaureate. They came into Diambars and didn’t even know how to read or write. Our aim is to put young people into active society.”

It’s working. Since the first intake graduated in 2008, roughly 50 Diambars students have gone on to university and eight, including Moustapha, have won football scholarships to colleges in the US.

One of the first students, Makhtar Mbow, got his Masters in economics and returned as the school’s assistant director.

Soccer success

And although it comes second to studies, the school’s success on the pitch is no less impressive.

Roughly 45 former students have become professional players; nearly a quarter of its 200 alumni. Nine are playing in Europe, and two have reached in the Premier League – the signed, framed shirts of Crystal Palace left back Pape Souare and Aston Villa midfielder Idrissa Gana Gueye hang proudly in the school’s reception.

Read: Why wrestling is booming in Senegal

But even with Diambars training, the European soccer dream is never easy.

Arfang Daffy, 24, plays in midfield in the academy’s pro team, currently fifth in Senegal’s top league.

He was loaned to Atletico Madrid’s B team in 2011 but, after an injury setback, his contract wasn’t renewed. He’s not the only one to try his luck in Europe and return, he says.

“All the young people here want to go to Europe, to play in the big clubs,” he adds quietly. “We know that not all of us will make it.”

Fortunately for Arfang, he combined his efforts on the pitch with a degree in business management.

“Some of us will get into the big clubs, others into average clubs, and some won’t get in anywhere,” he says.

“That’s why we do football and go to school too.”