Story highlights

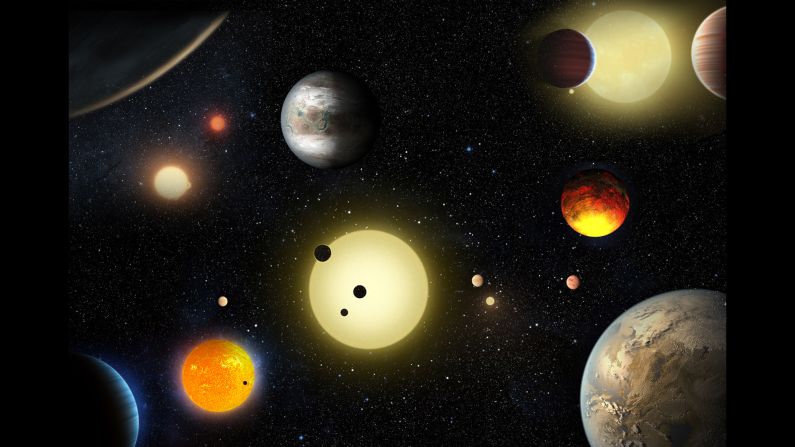

Researchers have discovered three potentially habitable, Earth-like worlds orbiting a dwarf star

The star and its planets are 40 light-years away in another star system

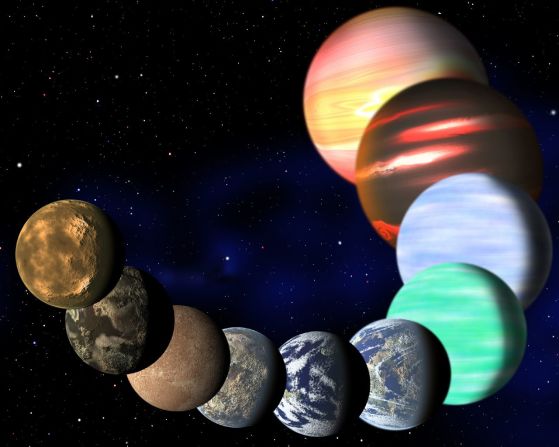

For the first time, researchers have discovered three potentially habitable, Earth-like worlds orbiting an ultracool dwarf star 40 light-years away in another star system, according to a study published in the journal Nature.

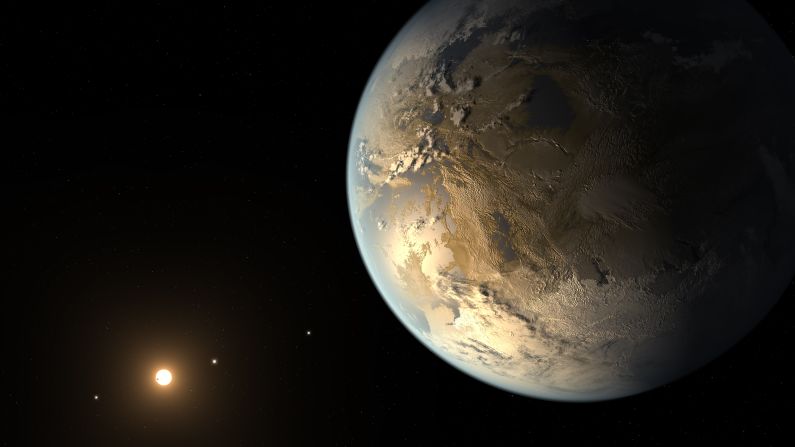

The ultracool dwarf star, known as TRAPPIST-1, isn’t the kind of star scientists expected to be a hub for planets. It’s at the end of the range for what classifies as a star: half the temperature and a tenth the mass of the sun. TRAPPIST-1 is red, barely larger than Jupiter and too dim to be seen with the naked eye or even amateur telescopes from Earth.

Where life might live beyond Earth

But these tiny stars, along with brown dwarfs, are long-lived, common in the Milky Way and represent 25-50% of stellar objects in the galaxy, said study researcher Julien de Wit, a postdoctoral associate with MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences.

They were largely overlooked until researcher Michaël Gillon of the University of Liège in Belgium decided to take a risk and study the space around one of these dwarves. It paid off.

Over the course of 62 nights from September to December 2015, researchers led by Gillon used a telescope, also called TRAPPIST (transiting planets and planetesimals small telescope), to observe its starlight and changes in brightness. The team saw shadows, like little eclipses, periodically interrupting the steady pattern of starlight. Using a telescope that can detect infrared light added an advantage that visible light camera programs don’t provide.

“It’s like standing in front of a lamp and throwing a flea across it,” said professor Adam Burgasser of the Center for Astrophysics and Space Science at the University of California San Diego. “It was only a 1% dip in light, but the specific pattern was a good sign of orbiting planets.”

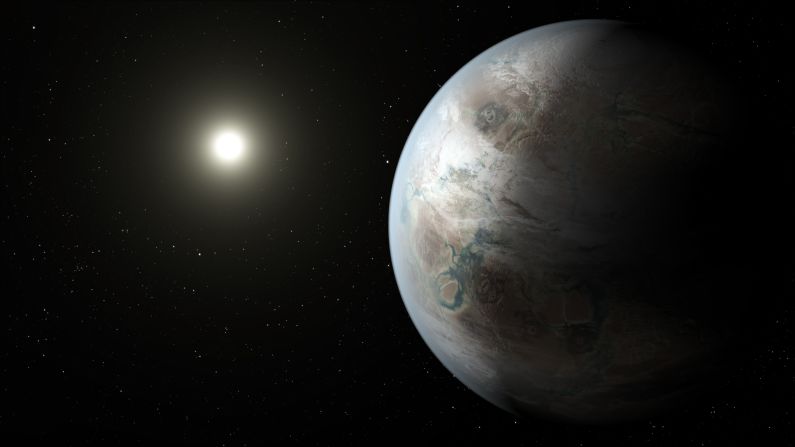

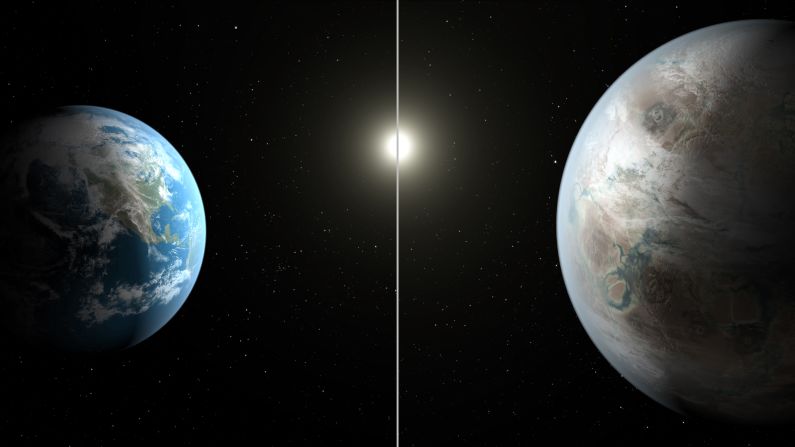

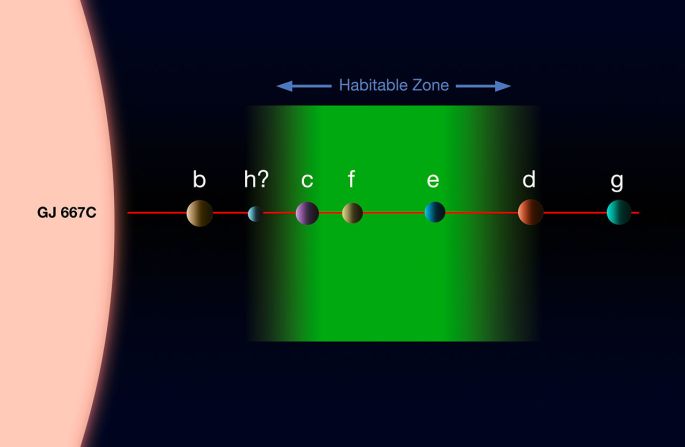

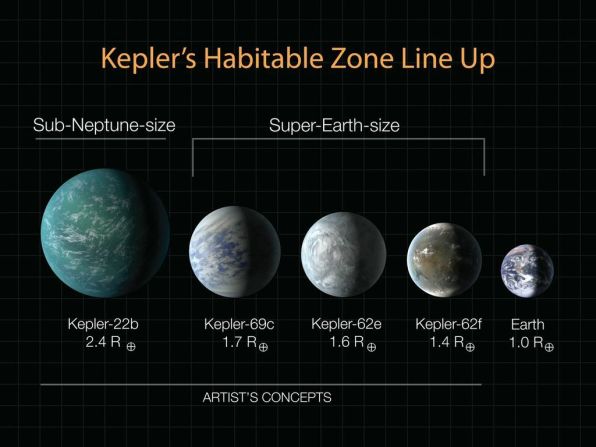

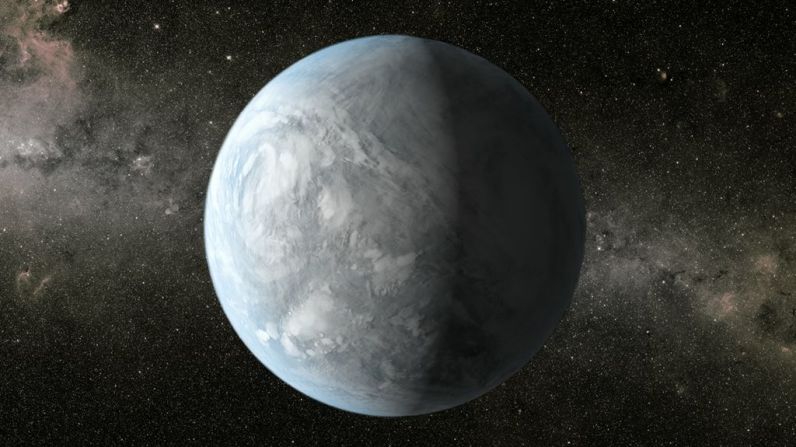

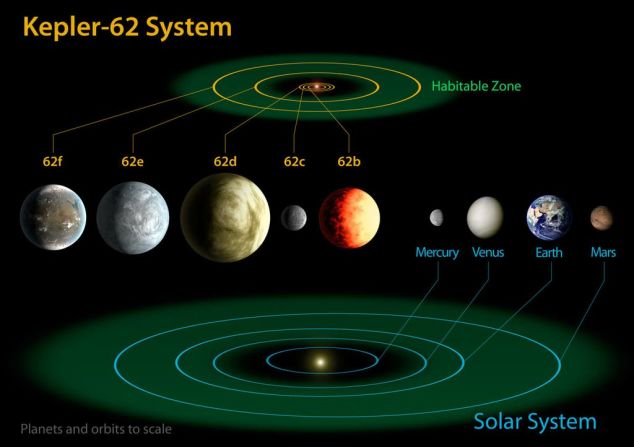

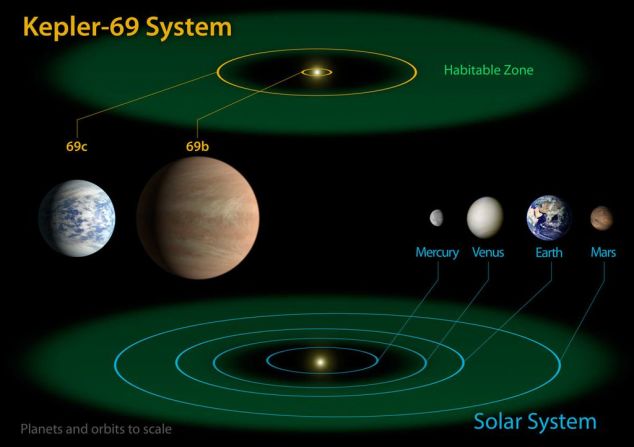

The planets are about the size of Earth and given the proximity of two of them to the dwarf star, they receive about four times the amount of radiation than we do from the sun, which suggests they are in the “habitable zone.” According to Burgasser, the “habitable zone,” determines how close a planet is to the star that it orbits and given the temperature of the planet based on that proximity, it could have water on the surface. This core ingredient for life as we know it also suggests there could be an atmosphere and habitable regions on the planets themselves.

Less is known about the third outer planet, which receives twice the amount of radiation that Earth does, but it is potentially in the habitable zone as well.

Like the moon, the researchers believe the two planets closest to the star are tidally locked. This means that the planets always face one way to the star. One side of the planet is perpetually night, while the other is always day.

These results are just the beginning of a study that will continue for years. The researchers are already working on observations to see if the planets have water or methane molecules.

The planets are the perfect target to be studied at 40 light-years away, but that doesn’t mean we will reach them anytime soon. With current technology, it would take millions of years for an expedition to reach these planets. But from a research perspective, they provide a close opportunity and the best target to search for life beyond Earth and our solar system. What we find also could change how we determine the creation of life as we know it.

The telescopes these researchers use to study the planets are even more precise than Hubble. In 2018, they can begin using the James Webb Space Telescope, which will allow the scientists to observe the shell of an atmosphere if it exists for these planets, and even what chemicals comprise that atmosphere. It will also provide more detailed information about the planets’ composition, temperature and pressure, according to de Wit.

The next generation of telescopes will also be able to search for the subtle signatures of biomarkers, like oxygen, de Wit said.

Burgasser is excited about what this discovery means for the future, which he anticipates will include more interest in these tiny stars and what they can support.

“We’ve shown that these kinds of stars are a way to find Earth-like planets,” he said. “Over the next few years, we can explore the space around this one and pin down their orbits and see if there are other planets in this system.”

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Burgasser, who has made the study of dwarf stars his life’s work, says that TRAPPIST-1 was initially studied quite a bit, but the planets around it have not been revealed until now.

“It’s like you’ve known this good friend your whole life and suddenly find out that they’re royalty,” he said. “What else could we find out about other ‘old friends’ that we previously studied if we went back?”