Editor’s Note: This essay is part of a column called The Wisdom Project by David Allan, editorial director of CNN Health and Wellness. The series is on applying to one’s life the wisdom and philosophy found everywhere, from ancient texts to pop culture. You can follow David at @davidgallan. Don’t miss another Wisdom Project column by subscribing here.

Story highlights

The books you read influence your life in deep and long-lasting ways

Reading has profound implications on long-term cognitive capabilities

Whenever I enter someone’s home, I’m drawn to their bookshelves. It’s not a conscious effort; it’s just the part of a house I find most interesting. Seeing someone’s books offers a glimpse of who they are and what they value. It also makes for good ice-breaker conversation. Some people like to snoop through medicine cabinets, but that only gives you insight into a person’s physical well-being. The books tell a tale about the person’s mind.

This proclivity has paid off for me big-time. Before we started dating, my now-wife, Kate, developed what she called the bookshelf theory of dating. She had met someone at a party in her apartment a couple of years earlier who asked questions about her books, one in particular. That was telling, Kate told her friends; interest in her bookshelf was a quality she wanted in a partner. Years later, on one of our early dates, I brought up the same book, still on her shelf, and she cut me off. “It was you! You were the person who asked me about my books. I developed a whole theory of dating around you!”

Our fate must have been written.

Bookshelves have been surprisingly good for me, but they hold tangible benefits for everyone. You may not have a biography written about your life, but you have a personal bibliography. And many of the books you read influence your thoughts and life in often deeper and longer-lasting ways than film, television, music and other attention-grabbing pleasures.

“How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book?” Henry David Thoreau asked rhetorically, referring to nearly everyone. That was long before there were ubiquitous screens, but it’s still true.

Books as therapy

If a book can change your life, why leave that to serendipity? The trend toward bibliotherapy – a strategy of seeking books that aid you through difficult times and aspects of your life – is starting to catch on.

“Reading literature can increase a person’s happiness, decrease stress, and unlock the imagination,” is how BiblioRemedy describes the goals of its bibliotherapy, in which a specialist talks to you about about the issues you’re wrestling with and recommends books to help you sort them out.

Ella Berthoud and Susan Elderkin, bibliotherapists at London’s School of Life, have written – what else? – a book on the topic. In “The Novel Cure: An A-Z of Literary Remedies,” they show how Gabriel Garcia Marquez can help overcome a fear of death and Patricia Highsmith can cure lovesickness.

We’ve probably all been bibliotherapists at some point. When I meet young people in the midst of their searching-for-the-meaning-of-life stage, I recommend “The Razor’s Edge” by W. Somerset Maugham. For those who’ve seen a thing or two, I’ve given “To Bless the Space Between Us,” John O’Donohue’s poems on the human experience. And for friends who have experienced true tragedy I have shared Pema Chodron’s “When Things Fall Apart,” in hopes it may offer them some guidance through their grief.

Books, and stories in particular, are probably the greatest source of wisdom after experience (as I argued on the TEDx stage, diving deep into the meaning of a single ancient Taoist parable). You aren’t just more knowledgeable the more you read, but you have more insight into life, love and the other big topics that matter most.

Reading as exercise

Even when we read for pleasure, we usually learn something (which you can rarely say of entertainment television). “Reading is to the mind what exercise is to the body,” wrote the English politician and writer Joseph Addison.

Research backs this up. “Literacy propels the development of new, neuronal networks in the brain – particularly in specific forms of connectivity between visual and language regions. That, in turn, create the potential for increasingly complex thought,” explained Maryanne Wolf, author of “Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain” and director of the Center for Reading and Language Research at Tufts University.

The benefits of a lifetime of reading are exponential and have “profound implications for the development of a wide range of cognitive capabilities,” wrote researchers in the Journal of Direct Instruction. The 2001 study showed language acquisition is more impacted outside of formal teaching settings, most profoundly from books. The exposure to vocabulary is so much greater from them than from television or from spoken language that even a preschool book offers more new words than listening to an adult TV show or a conversation between two college-educated adults. Strong early reading skills have also been linked to higher intelligence as adults.

Fiction is just as insightful as nonfiction, if not more so. Is there a reference book about love, for example, that is better at capturing its essence than Ian McEwan’s “Atonement”? Tim O’Brien effectively illustrates in “The Things They Carried” that just because something didn’t happen doesn’t mean it’s not true; it may be more true because it’s fiction. And reading fiction enhances connectivity in the brain and improves brain function in ways nonfiction doesn’t, according to researchers at Emory University in a study from 2013.

Let’s not discriminate, though. Nonfiction, fiction, reference books, children’s lit, sci-fi, poetry: All are portals of discovery and meaning. Books, rather than bite-sized posts and podcasts, take you spelunking instead of merely peering into the cave.

Your ideal bookshelf

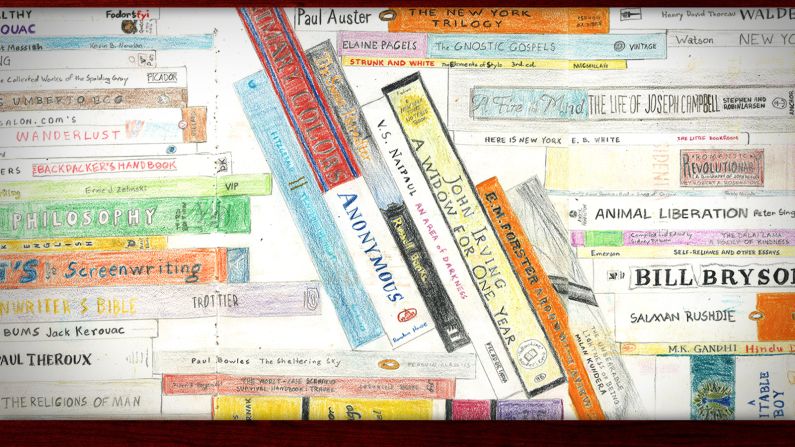

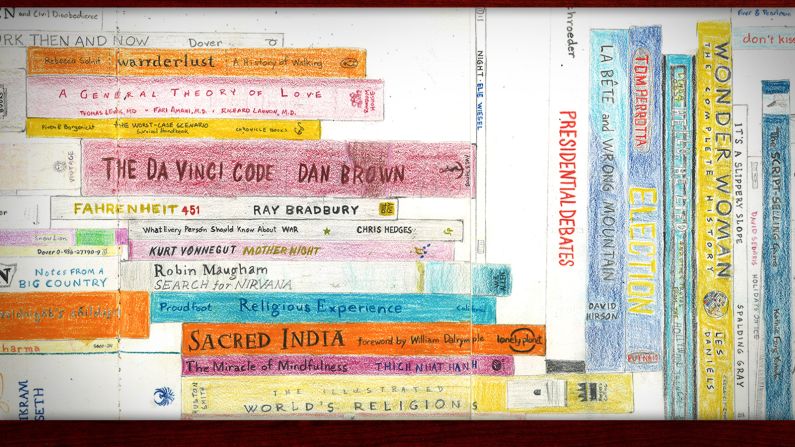

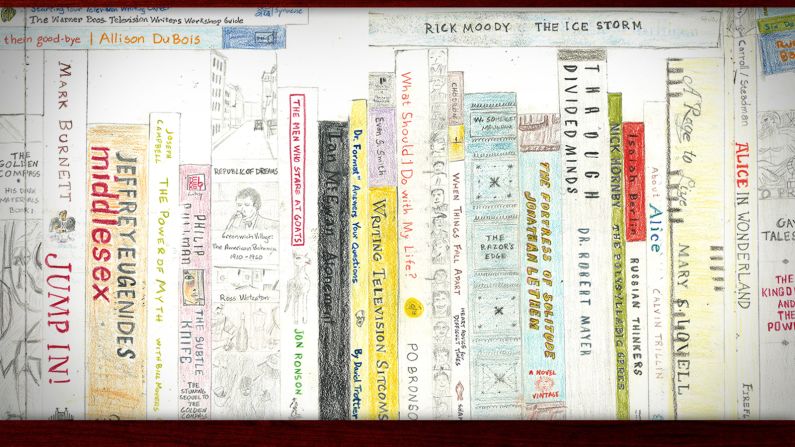

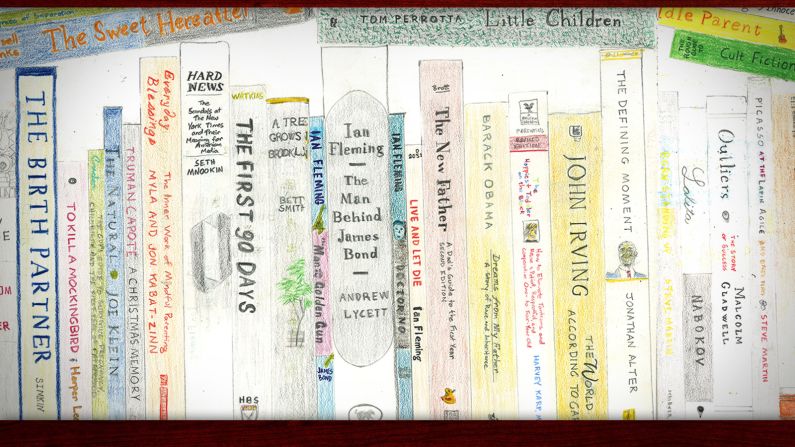

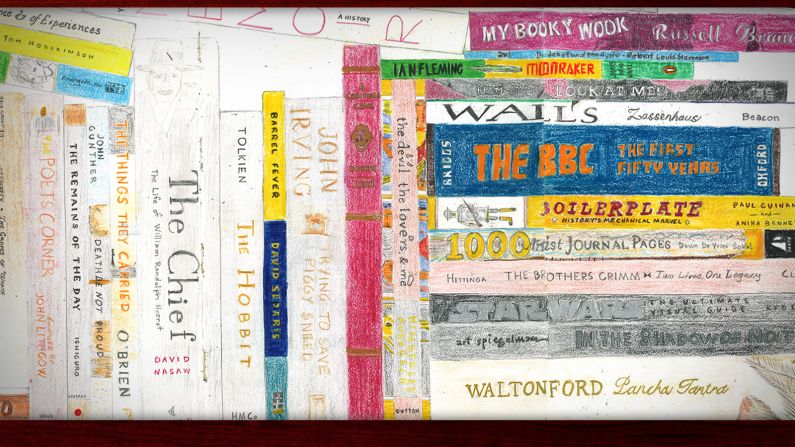

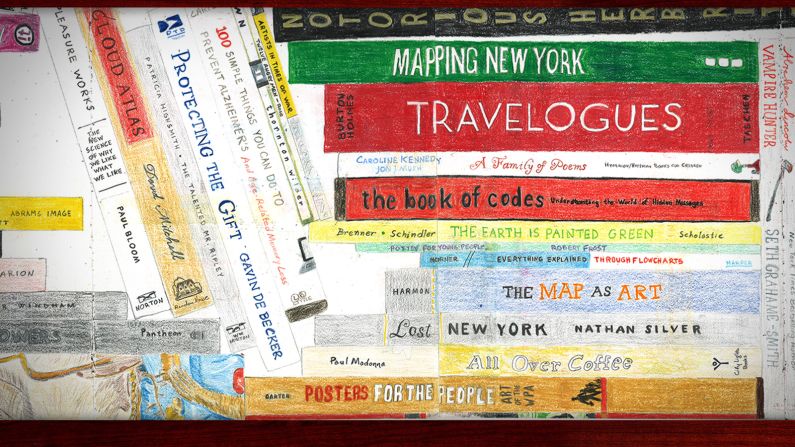

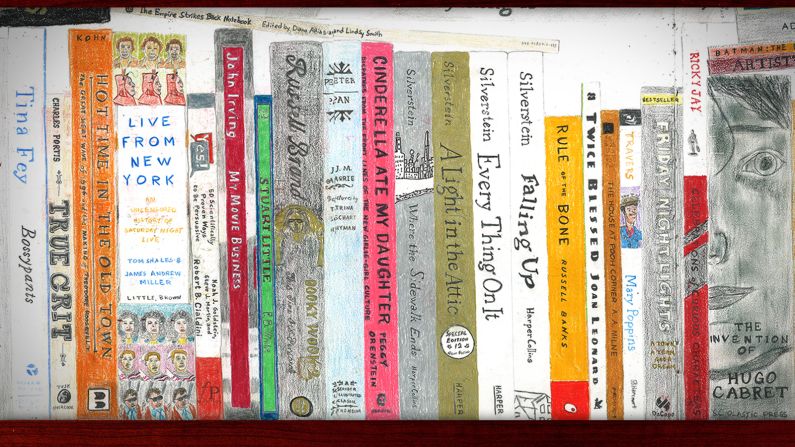

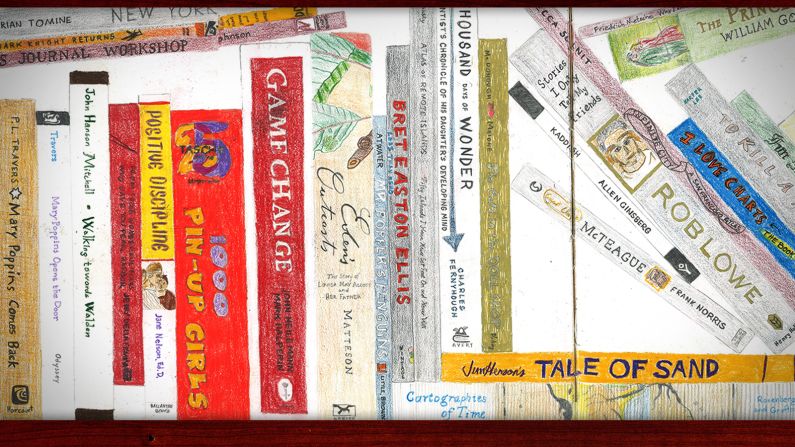

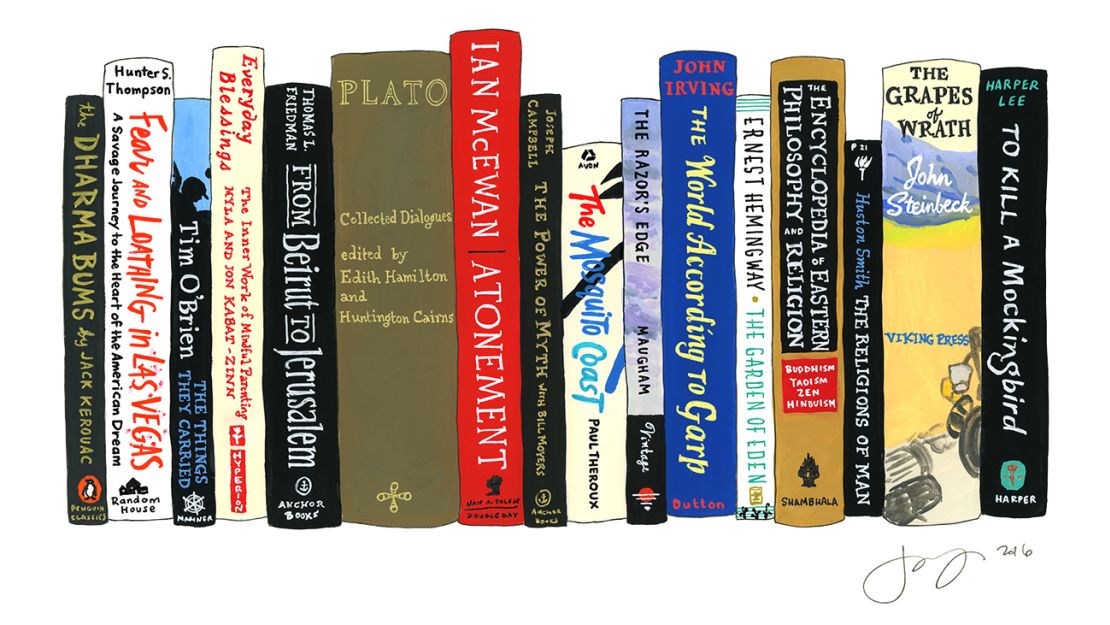

The impact of books on the lives of people is the inspiration behind a fascinating volume titled “My Ideal Bookshelf,” in which Thessaly La Force interviewed a wide variety of writers and thought leaders, from Malcolm Gladwell to Patti Smith, about the books they value most. Artist Jane Mount then painted their books on a virtual bookshelf to illustrate each profile.

“The reason I started the project was by looking at people’s bookshelves and thinking about what that taught me about them,” Mount explained. She and La Force agreed it would be fascinating to see the ideal bookshelves of certain people (not necessarily famous ones), so they began asking. And by painting the books those individuals considered their favorites, or the ones that made them who they are, or changed them in some way, it creates what Mount describes as a “portrait from the inside … almost like a book aura.”

“It’s fascinating that you can take something so basic as a book spine – just a rectangle with words – but it represents so many huge ideas about what’s inside.”

What my ideal bookshelf might say about me

Mount’s theory about why books affect us in deeper ways than other media is that “when you’re forced to imagine things, they stick in your brain longer.” And after painting more than 1,000 ideal bookshelves (you can commission your own through her website), she has noticed a trend toward books that formed a strong emotional bond with the reader when they were young. The most recurring book on people’s commissioned bookshelves? Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” followed by J.D. Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye.”

It’s a fun and insightful exercise to ponder your ideal bookshelf. Which books have influenced you the most? Which volumes make your heart soar or brain buzz? Which do you reread because, at different stages of life, they reveal new insights? Or which ones do you find so enjoyable that you return to immerse yourself in the story again and again? And what do they collectively say about you?

To e-book or not to E?

As for e-books, warming your hands over the Kindle is fine, too, arguably useful when traveling and more environmentally friendly. And audio books, when well produced, are practically a new art form. But personally, I find there’s something less comforting about pixelated and audio books, and less satisfying about completing them. They’re less read-in-the-bathtub friendly and more expensive when dropped. There’s even research that shows electronic book consumption inhibits reading comprehension and recall, if you want a scientific reason to eschew them.

But consuming good books is more important than the medium in which you do so.

And if you prefer e-books, that’s another argument for maintaining a virtual bookshelf. “People want to own physical books less but they still want a record,” said Mount.

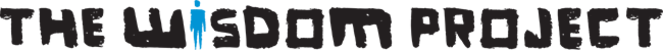

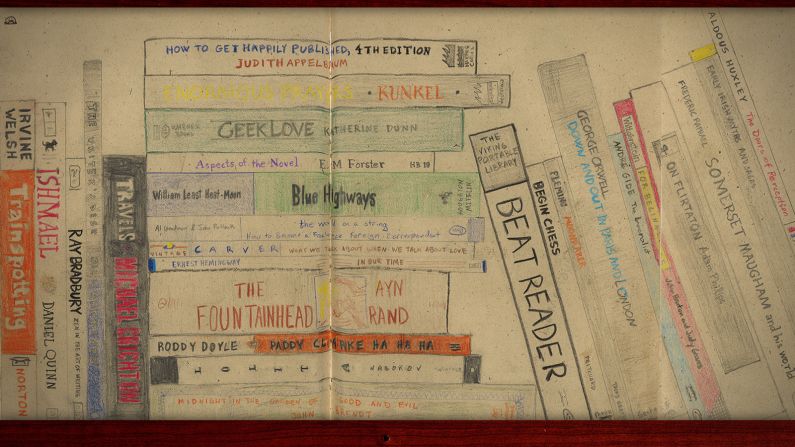

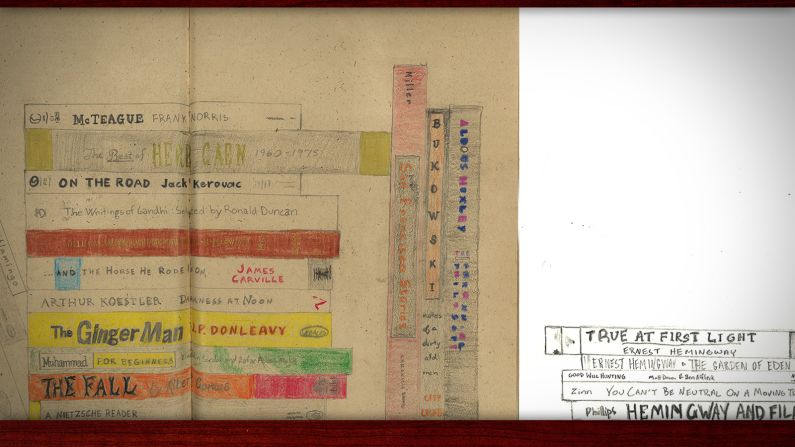

It was for a similar reason that 20 years ago I began drawing books on a virtual bookshelf of my own.

The 20-year bookshelf

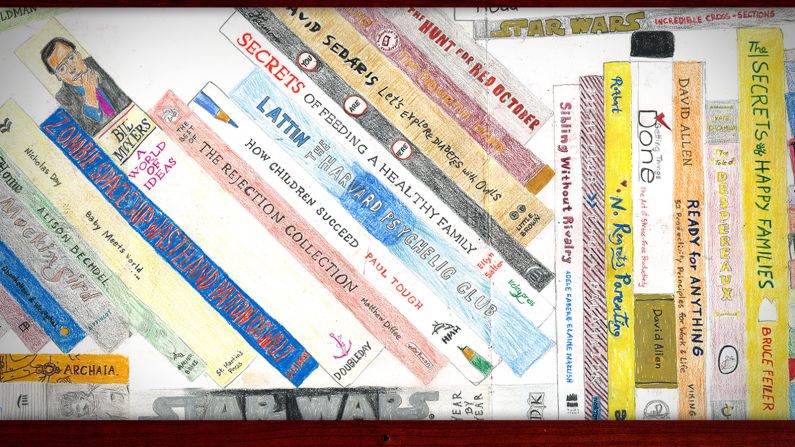

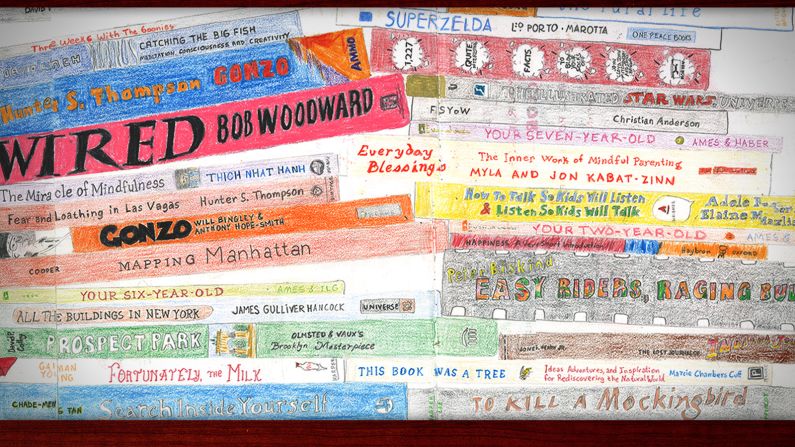

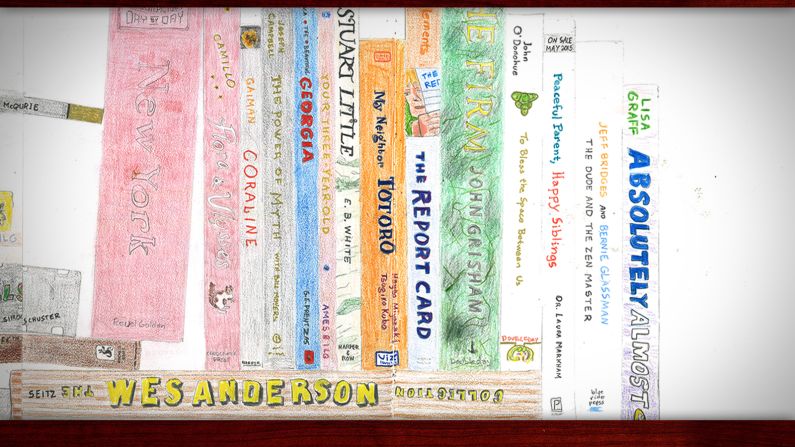

The gallery above is my hand drawings of the spines of every* book I’ve read since my last year of college, sketched in various writers’ notebooks I’ve kept over two decades. (*Well, not every kids’ book that I read to my young children, but some of the better ones.) Spines, as Mount points out in her book, are “totally lost in the digital age.”

The drawings started out as an artistic lark and ended up a literary timeline of my adult life. I love looking them over and seeing the books that jog memories of eras of my life: what I read my middle school students as a reading teacher in Teach For America (including “The Catcher in the Rye”), while living in Dublin, Ireland (“The Portable Beat Reader”), living in San Francisco (“McTeague” by Frank Norris), traveling around the world for a year (Paul Bowles’ “The Sheltering Sky” in Morocco, Vikram Seth’s “A Suitable Boy” on long train rides in India), starting my job at The New York Times (Gay Talese’s “The Kingdom and the Power”), becoming a father (“Protecting the Gift” by Gavin de Becker), and on long flights overseas while working for the BBC (Russell Brand’s “My Booky Wook”).

Many moves, plus access to great libraries in various cities, have meant I’ve only retained a small fraction of the books I’ve read, no matter how much I’ve loved them. And speaking of retained, my shelf is also a reference – an aide-memoire, as Proust might put it – when I want to recommend something I can’t quickly recall.

There are apps/sites that can help you track your reading consumption. The literary social network Goodreads.com, bought by Amazon, is probably the largest. But by drawing the book spines myself, I see the exact edition and copy of the one I read. And the act of drawing them is a slow, meditative art experience I look forward to with every new one. The only downside I’ve found with this project is that it has made me a bit OCD about reading entire books. If I read a parenting book for insight on my 4- and 8-year olds, I’ll read the chapter on babies too, because I don’t think it counts for the bookshelf otherwise.

There’s a desire in our collective human experience to mark ephemeral time with the corporeal. For some, tattoos connect them to dates and places of their lives. Others collect vials of sands from beaches, or coffee mugs from the cities they visit. Many keep journals, many more create photo albums, and many more chronicle on Facebook. The virtual bookshelf is just another form of that. A great one, I’d argue.

So, whatever else you’re bingeing on these days – podcasts, magazines, Netflix, Candy Crush, cat videos or CNN news – make sure you’re still getting a steady, healthy diet of pulp. And keep your books on a bookshelf, real or virtual, to enjoy the memories.