Story highlights

NEW: NFL lawyer says the remarks are consistent with the league's stance and won't affect a settlement agreement

NFL VP cites research establishing CTE link and says the question now is "where do we go from here with that information"

An attorney for some former players says that "directly contradicts" NFL position in lawsuit

For the first time, the National Football League has publicly acknowledged a connection between football and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the brain disorder better known as CTE.

Jeff Miller, the NFL’s senior vice president of health and safety policy, was part of a round-table discussion with the U.S. House Committee on Energy and Commerce on Monday when Rep. Jan Schakowsky asked him directly: “Mr. Miller, do you think there is a link between football and degenerative brain disorders like CTE?”

“The answer to that question is certainly yes,” Miller said.

The NFL issued a statement on Tuesday, saying “The comments made by Jeff Miller yesterday accurately reflect the view of the NFL.”

Why now for the NFL?

For years, the NFL has avoided saying whether football was related to CTE and deferred to the medical community’s findings on the matter.

So why the change now?

Previously, the NFL has said that it was waiting on more brain studies, according to CNN’s Coy Wire, who played nine seasons in the league.

“There were simply not enough studies or medical proof for the league to make a direct connection between football and CTE,” Wire said.

However, recent studies at Boston University may have been an impetus for the change in the league’s perspective.

In his response on Monday, Miller referenced Dr. Ann McKee, a neuropathologist and an expert in neurodegenerative disease at Boston University School of Medicine.

“I think certainly, based on Dr. McKee’s research, there’s a link, because she’s found CTE in a number of retired football players,” Miller said. “I think the broader point … is what that necessarily means and where do we go from here with that information.”

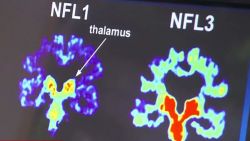

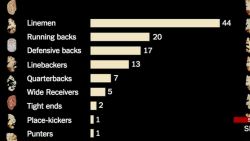

“I unequivocally think there’s a link between playing football and CTE,” McKee said Monday. “We’ve seen it in 90 out of 94 NFL players whose brains we’ve examined, we’ve found it in 45 out of 55 college players and six out of 26 high school players. Now I don’t think this represents how common this disease is in the living population, but the fact that over five years I’ve been able to accumulate this number of cases in football players, it cannot be rare. In fact, I think we are going to be surprised at how common it is.”

Several former NFL players, including some prominent members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, have been found to have had CTE.

Most recently, Ken Stabler, who died in July from cancer, was posthumously elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in February. Earlier that week, researchers at Boston University said that Stabler suffered from CTE.

Hall of Fame class of 2015 member Junior Seau also was elected after his death. He was 43 when he killed himself in May 2012 with a gunshot wound to the chest and was posthumously diagnosed with CTE.

Mike Webster, the Pittsburgh Steelers center who was profiled in the movie “Concussion,” was the first former NFL player to be diagnosed with CTE. He died of a heart attack at age 50.

Perhaps the best-known person diagnosed with CTE was Hall of Famer and revered sportscaster Frank Gifford; he died of natural causes in August at age 84.

The NFL Players Association had no comment on Miller’s statement, but referred CNN to a news release it issued two weeks ago headlined “NFLPA Letting Medical Science Point the Direction in Fight to Protect Players’ Health and Safety.”

What happens with lawsuits?

In June 2015, a federal judge approved a class-action lawsuit settlement between the NFL and thousands of former players. The agreement provides up to $5 million per retired player for serious medical conditions associated with repeated head trauma.

While the lawsuit was a combination of hundreds of actions brought by more than 5,000 ex-NFL players, the settlement applies to all players who retired on or before July 7, 2014, according to Judge Anita Brody’s 132-page decision. It also applies to the family members of players who died before that date.

However, that is all on hold for now. According to the NFL concussion settlement website, “no claims for benefits can be submitted now and none have been submitted. No awards have been issued.”

“We welcome the NFL’s acknowledgment of what was alleged in our complaint: that reports have associated football with findings of CTE in deceased former players,” Christopher Seeger, co-lead counsel for the retired NFL player class plaintiffs, said Tuesday in a statement. “Retired NFL players brought this case to obtain security and care for the devastating brain injuries they were experiencing at a rate much greater than the general population. The settlement achieves that, providing immediate care to the sickest retired players and long-term security over the next 65 years for those who are healthy now but develop a qualifying condition in the future.”

Following Miller’s comments Monday, attorney Steven Molo, who represents some former players who opted out of the concussion lawsuit settlement, wrote to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. In the letter, he said that the NFL’s testimony “directly contradicts its positions in this case,” saying the NFL had previously said “the speculation that repeated concussion of subconcussive impacts cause CTE remains unproven.”

“The NFL’s statements make clear that the NFL now accepts what science already knows: a ‘direct link’ exists between traumatic brain injury and CTE,” Molo wrote.

In an email to CNN on Tuesday, Molo said he hopes that this new NFL stance will affect all former players and members from the settlement class.

“After the Third Circuit recognizes the unfairness of the current settlement and returns it to the district court for further negotiations, I hope the NFL’s recent admission will prompt it to provide the benefits and care that retired players suffering with CTE deserve,” Molo wrote.

In response to Molo’s letter, Paul Clement, a lawyer for the NFL, wrote to the appeals court to say Miller’s comments were consistent with the NFL’s position on the issue and wouldn’t affect the settlement agreement.

“The NFL has previously acknowledged studies identifying a potential association between CTE and certain football players, including Dr. McKee’s work, to which the NFL has contributed funding,” Clement wrote.

“Conspicuously omitted from Mr. Molo’s letter is any reference to either Mr. Miller’s comments on the limited knowledge of the ‘incidence or the prevalence’ of CTE or the District Court’s express finding that the scientific community indisputably acknowledges that the causes of CTE remain unknown and the subject of extensive medical and scientific research.”

Clement ended by saying Miller’s statements “have no bearing on the pending appeal.”

What does this mean for current players?

In the short term, the NFL continues to make changes when it comes to player safety, referencing improvements in equipment and focusing on the concussion issue.

“We learn more from science,” NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell said February 5 at his news conference ahead of Super Bowl 50. “We learn more by our own experience and we have made great progress. We continue to make rule changes to our game to make the game safer and protect our players from unnecessary injury, from acts that we see can lead to increased probability of an injury.”

Currently, the NFL is more popular than ever. Ratings and revenues continue to soar. Super Bowl 50 averaged 111.9 million viewers. NFL revenues are projected to be more than $13 billion in 2016, according to Forbes.

But current NFL players aren’t eligible to collect in the concussion settlement. And CTE is a disease that only can be diagnosed postmortem. There is no cure.

The problem isn’t limited to football. Athletes from other sports, such as former Major League Baseball player Ryan Freel, former NHL player Steve Montador and wrestler Chris Benoit, were found to have had CTE. Recently, former U.S. women’s soccer star Brandi Chastain announced she has agreed to donate her brain to Boston University for research into CTE.

Will there be a drop-off in participation levels in any of these sports? Will there be more lawsuits? That all remains to be seen. But Dr. Bennet Omalu, profiled in the movie “Concussion,” said because a link has been established, filing a lawsuit is less likely because a judge could say that the filing party should know the risks.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

“It’s like if you smoke now, you can’t sue the cigarette industry,” Omalu said. “It’s already established. The same applies to football. Moving forward, you can’t sue someone, claiming that someone else is responsible for your injuries.”

CNN’s Steve Almasy, Nadia Kounang, Ralph Ellis and David Close contributed to this report.