Story highlights

A new study finds that the rate of unintended pregnancies has decreased dramatically in recent years

Nearly half of all pregnancies in the United States are still unintended

The high rate of unintended pregnancies in the United States could be on the decline for the first time in decades, according to a new study.

The researchers found that the proportion of pregnancies in the United States that were unintended dropped from 51% of all pregnancies between 2006 to 2010 to 45% between 2009 and 2013. Looking at women 15 to 44 years old in the general population, they determined that 54 out of 1,000 women had an unintended pregnancy between 2006 and 2010, compared with only 45 out of 1,000 in the more recent period.

The study looked at data from nearly 2,000 pregnancies and whether the women had wanted to get pregnant, which were collected as part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Survey of Family Growth. Researchers considered a pregnancy unintentional if a woman said she never wanted to have a child or did not want to have a child yet.

The researchers compared the rate of unintended pregnancies in the most recent survey, which was carried out between 2009 and 2013, with the rate from the previous survey period, from 2006 to 2010.

“This is a very exciting thing to see because the rate has been somewhat stagnant for quite a while, and unintended pregnancy is a key measure of the extent to which American women are able to achieve their childbearing goals,” said Lawrence B. Finer, director of domestic research at the Guttmacher Institute, a nonprofit research and policy think tank. Finer led the new study, which was published on Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In addition to the effects of unintended pregnancies on women, they have been associated with worse health outcomes for children. Research has found that infants of unintended pregnancies are less likely to receive prenatal care or be breastfed, and more likely to be have low birth weight.

Prior to the current study, the rate of unintended pregnancies declined slightly between the late 1980s and mid-1990s, which Finer attributed to an increase in use of birth control pills and other forms of contraception. Then, between 2001 and 2008, the rate started to climb back up, which could have been because of upticks in populations such as poor and Hispanic women, who are at increased risk of unintended pregnancy.

“You have to squint really hard to make much of the movement (in the unintended pregnancy rate) over the last 20 years until now,” said James Trussell, a senior research demographer in the Office of Population Research at Princeton University who was not involved in the current study. “This is an extremely welcome decline.”

But there’s still reason for concern.

“Although it is nice to see that decline, it is still troubling that such a significant proportion of pregnancies are unintended. Certainly we would hope that proportion would continue to decline,” Finer said.

Why the rate of unintended pregnancies is dropping

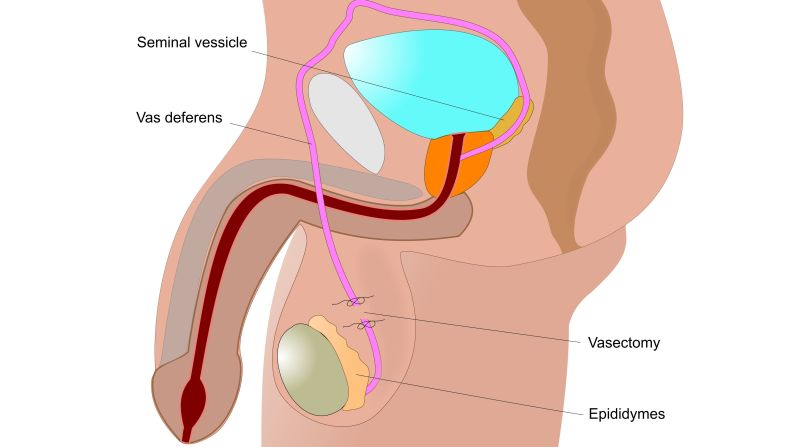

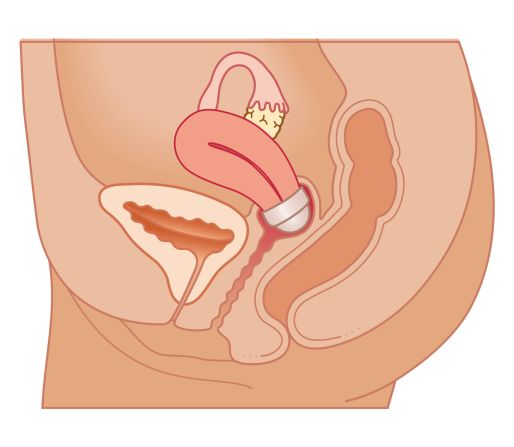

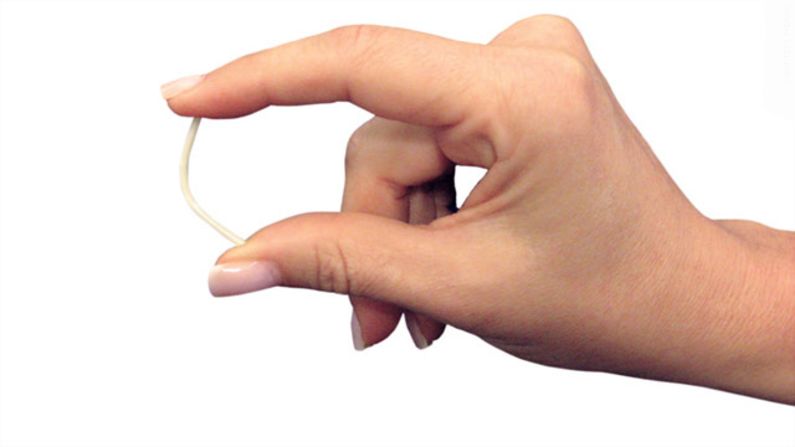

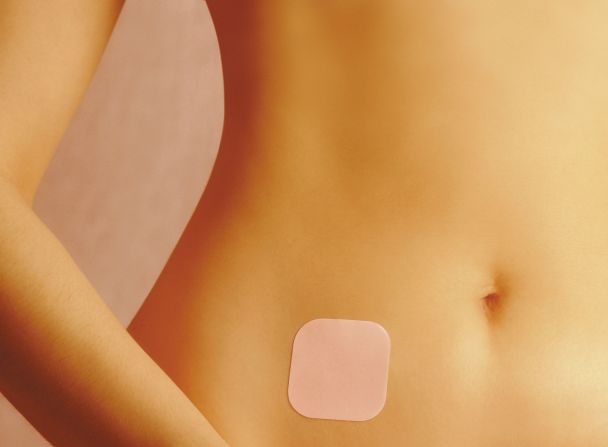

A big part of the reason for the decline, at least so far, is the “pretty significant increase in women using long-acting contraceptive methods like the (intrauterine device) in recent periods,” Finer said. These methods, such as the levonorgestrel and copper IUD and birth control implants, are associated with failure rates of less than 1%, while the failure rates of birth control pills and condoms are about 9% and 18%, respectively.

The number of women using IUDs and other highly effective forms of contraception will probably only increase now that the Affordable Care Act requires insurers to cover contraception as part of preventive health care, Finer said. This provision in the Affordable Care Act only took effect near the end of the most recent time period in the study.

In order to make highly effective contraceptives available to women, providers have to be trained in how to use them and how to talk with their patients about them, said Cynthia Harper, professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences in the Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health at the University of California-San Francisco School of Medicine.

“Right now the biggest reason that women are not using (long-acting contraceptives) is that they don’t know about them,” said Harper, who runs a training program helping physicians and nurse practitioners learn about these methods. However, some women decide these methods are not for them if, for example, they do not like the idea of having a device implanted in them or they do not like the side effects, which can include lighter menstrual bleeding and spotting with levonorgestrel IUDs and heavier bleeding with copper IUDs, she said.

“We still have a far way to go till all young people know about these methods,” Harper said. Rates of unintended pregnancies are generally highest among women 18 to 25 years of age, she added.

Who’s most at risk for unintended pregnancies

The current study found the unintended pregnancy rate took a nosedive among women of all ages, including those 20 to 24 years of age, who have the highest rate. It also found a drop in unintended pregnancy rates among women of all backgrounds, including black and Hispanic women and women of low socioeconomic status and education level, who traditionally bear the brunt of unintended pregnancies.

“This is really the first time we’ve seen such a broad-based decline. In the past, more advantaged groups have had declines and more disadvantaged groups have had increases,” Finer said.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

However it is a “glass is half full and half empty” situation, Finer said. Black women were still twice as likely as white women to have an unintended pregnancy. Women below the poverty level were still about five times as likely as women in the highest income group.

For all groups of women, improved access to contraception is the most important way to decrease unintended pregnancies, Finer said.

The current study found that 42% of unintended pregnancies ended in abortion between 2009 and 2013, similar to the rate of 40% between 2006 and 2010. One study of women seeking to terminate their pregnancies found that 40% reported having difficult accessing contraception.

Although Finer’s study did not look at whether women who had unintended pregnancies were less likely to have used contraception, data from other studies “suggest a disproportionate share of unintended pregnancies are to women who are not using any contraceptive,” Finer said.