Story highlights

Ground control do not expect further contact from Philae comet lander

ESA scientists say comet's environment too cold for space probe to operate

It was the intrepid little space probe that captured our imaginations. But the time has come to say farewell to the Philae lander.

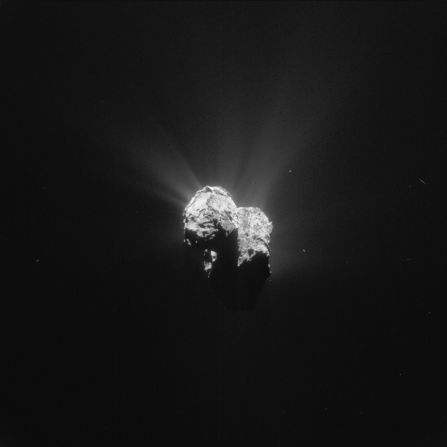

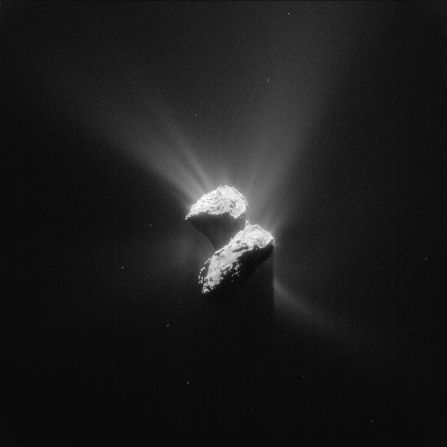

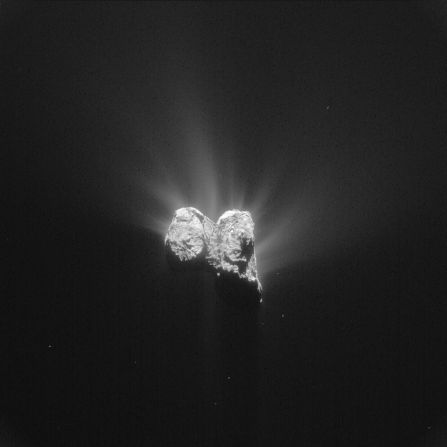

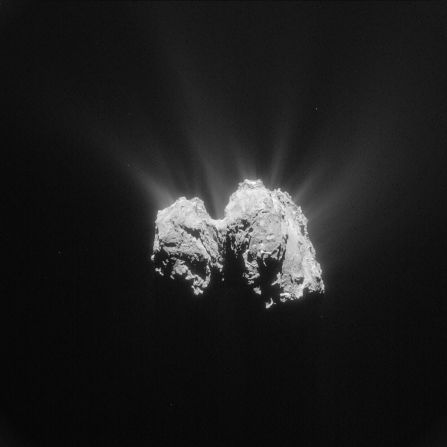

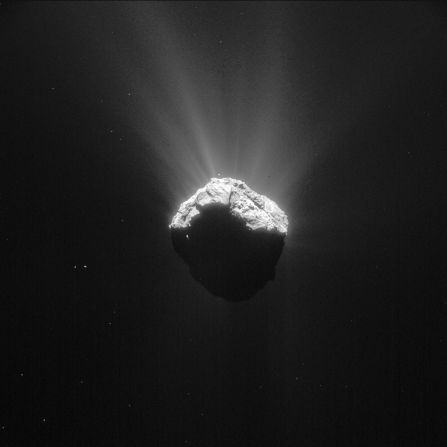

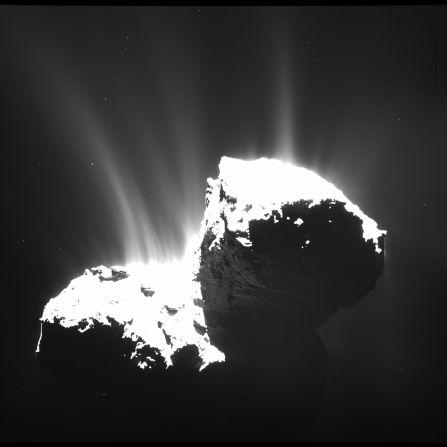

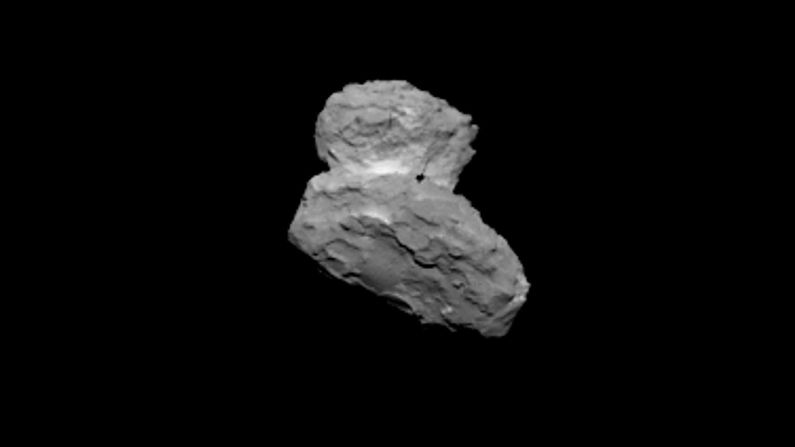

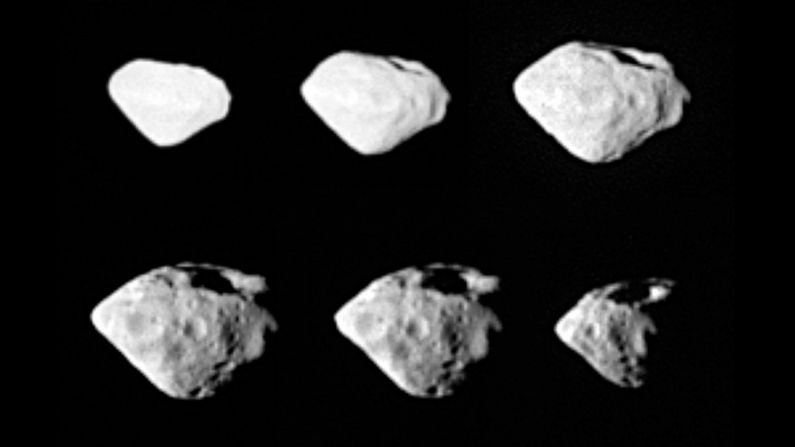

Scientists from the German Aerospace Center (DLR) have given up hope of establishing further contact with the comet lander, currently perched on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

“Unfortunately, the probability of Philae re-establishing contact with our team at the DLR Lander Control Center is almost zero, and we will no longer be sending any commands,” said Stephan Ulamec, Philae project manager.

“It would be very surprising if we received a signal now.”

While sad, the announcement is perhaps to be expected given a recent last-ditch attempt to wake Philae ended in failure last month.

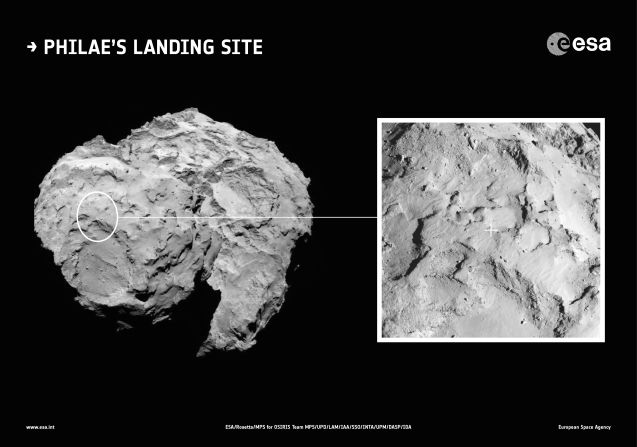

Ground control believe the probe is probably ice-free, but most likely “covered in dust” and unable to function due to the extremely cold environment.

Comet 67P is now over 350 million kilometers away from the sun where night temperatures can fall below minus 180 degrees Celsius (minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit) – significantly colder than 50 below zero degrees Celsius (minus 58 degrees Fahrenheit) it was designed to operate in.

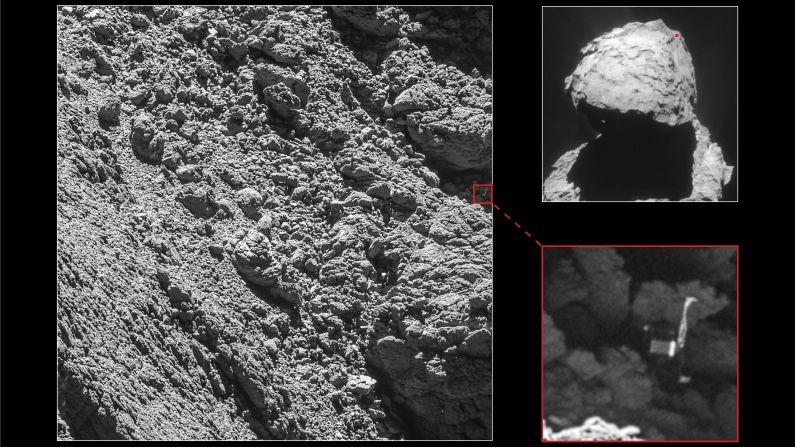

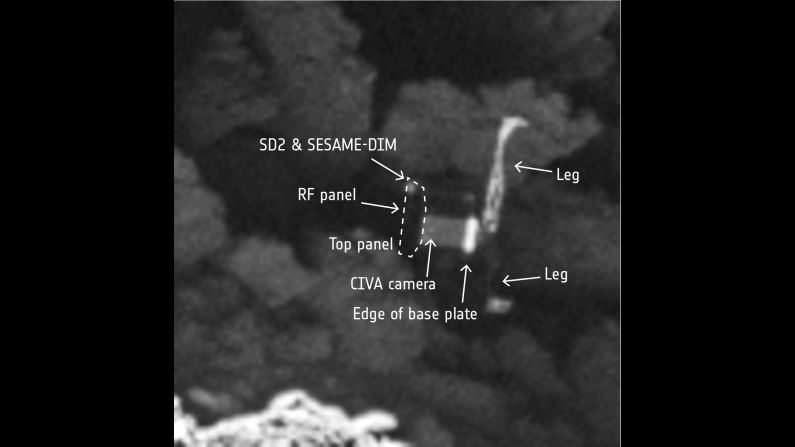

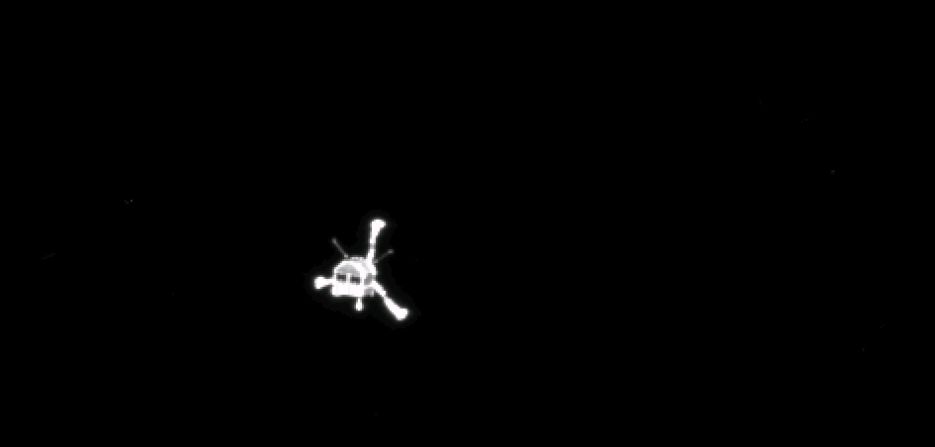

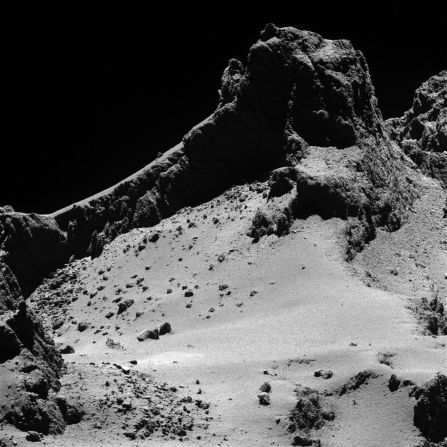

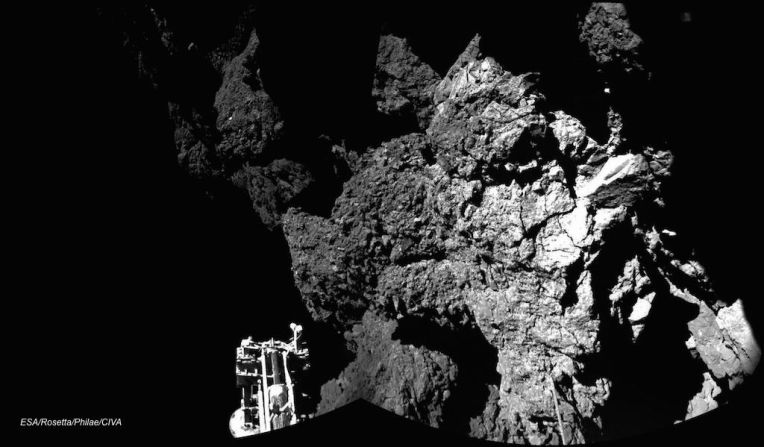

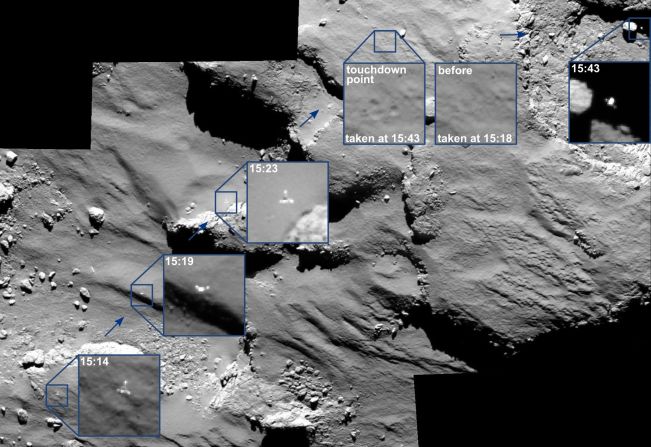

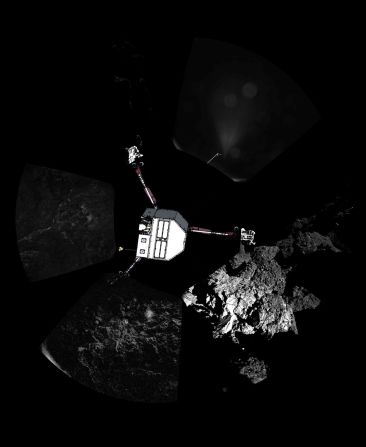

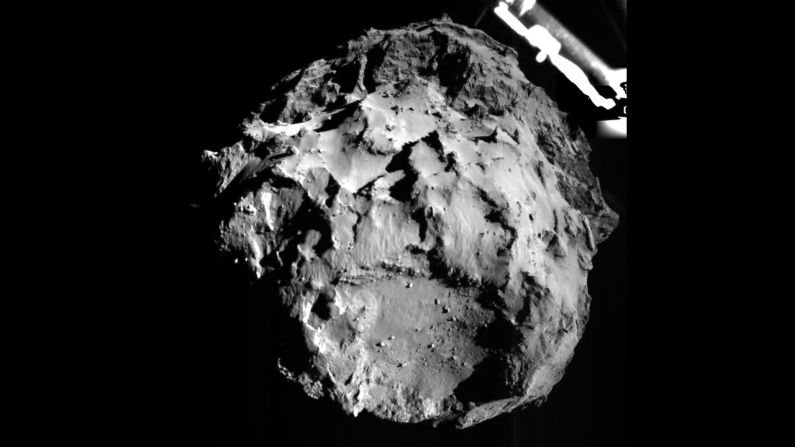

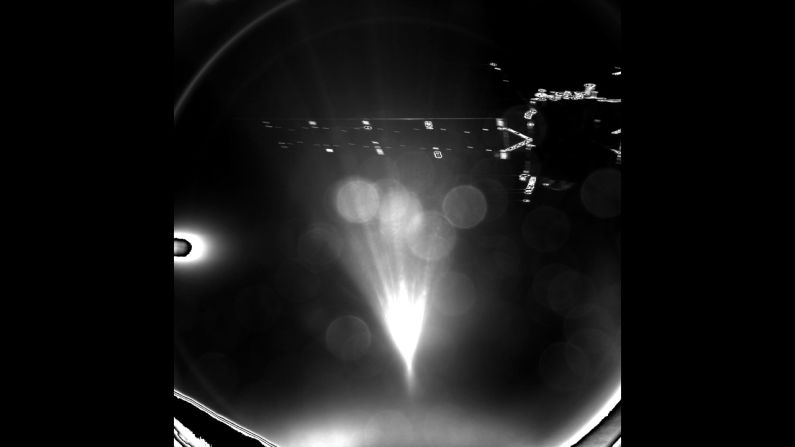

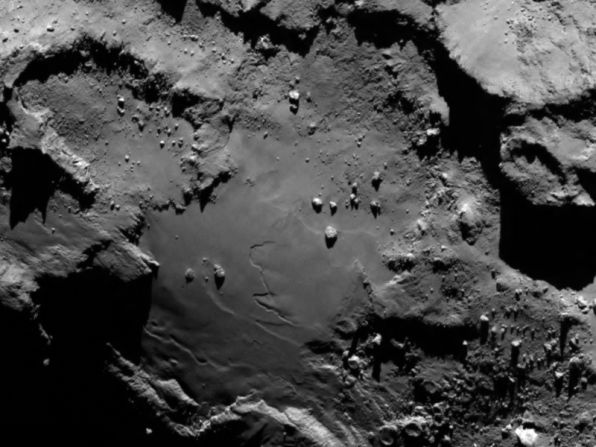

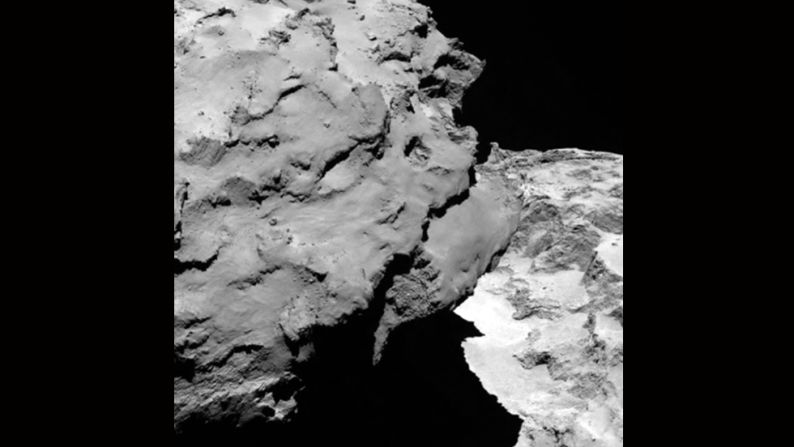

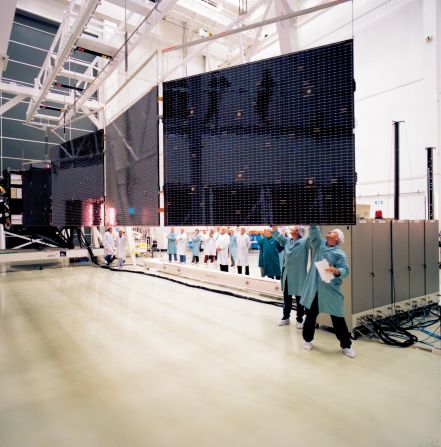

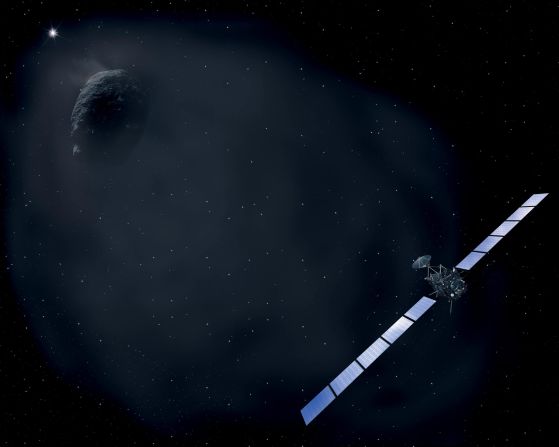

Philae was deployed from its mothership Rosetta in November 2014 and despite a successful landing, its position in the shade made powering the onboard solar-driven batteries problematic.

The probe last made contact in July 2015 when it sent information to European engineers, who were again unable to stabilize contact. It is believed a failure in the lander’s transmitter is the cause of its irregular communications.

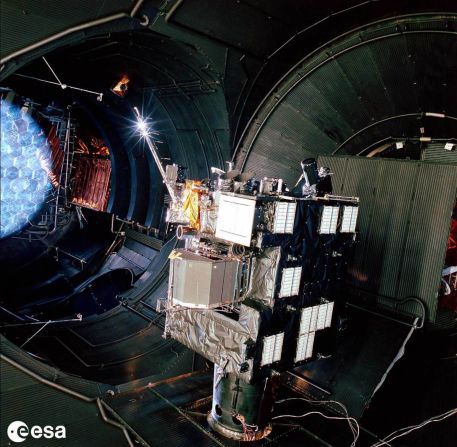

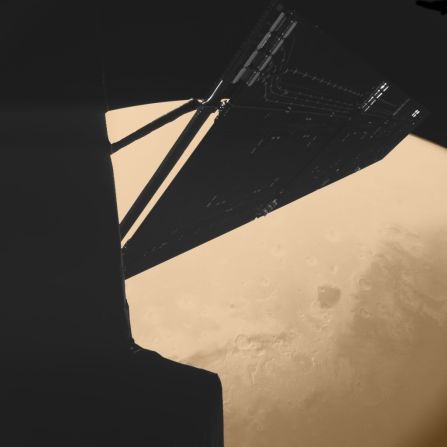

Meanwhile, the Rosetta craft will continue to orbit the comet undertaking scientific experiments until September.

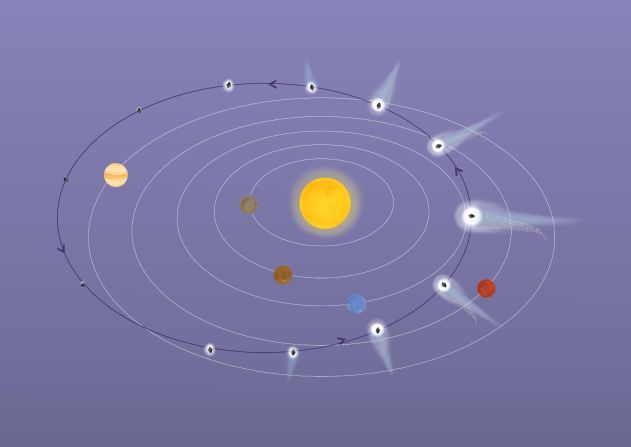

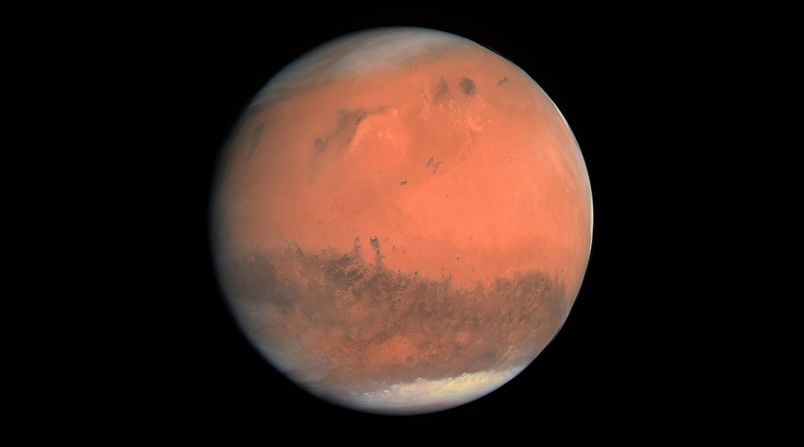

Led by the European Space Agency (ESA), which heads up a consortium including NASA , Rosetta chased Comet 67P around the solar system for a decade – tasked with a quest to find answers about our own origins in the universe.

Since bouncing on to the surface, Philae has provided the ESA with invaluable scientific data including the dramatic discovery of 16 “carbon and nitrogen-rich” organic compounds, supporting the theory that the building blocks of life could have been brought to Earth by comets.

“The Philae mission was one-of-a-kind – it was not only the first time that a lander was ever placed on a comet’s surface, but we also received fascinating data,” says Pascale Ehrenfreund, Chair of the DLR Executive Board and a participating scientist on the mission.

“Rosetta and Philae have shown how aerospace research can expand humankind’s horizon and make the public a part of what we do.”