Story highlights

Officials link Zika, a mosquito-borne virus, to a surge in a newborn neurological disorder

"If families can put off their pregnancy plans, that's what we're recommending," doctor says

Brazilian health officials are dishing out some unusual advice these days: Don’t get pregnant.

That’s the message for would-be parents, especially in the country’s northeast, after officials linked a mosquito-borne virus called Zika to a surge in newborn microcephaly, a neurological disorder that can result in incomplete brain development.

“It’s a very personal decision, but at this moment of uncertainty, if families can put off their pregnancy plans, that’s what we’re recommending,” Angela Rocha, the pediatric infectologist at Oswaldo Cruz Hospital in Brazil’s hardest-hit state, told CNN.

Behind Brazil’s outbreak

More than 2,400 suspected cases of microcephaly have been reported this year in 20 Brazilian states, compared with 147 cases last year. Doctors are investigating 29 related infant deaths.

Microcephaly results in babies being born with abnormally small heads that cause, often serious, developmental issues and sometimes early death.

As a result, six states have declared a state of emergency. In Pernambuco state alone, more than 900 cases have been reported.

“These are newborns who will require special attention their entire lives. It’s an emotional stress that just can’t be imagined,” Rocha said. “Here in Pernambuco, we’re talking about a generation of babies that’s going to be affected.”

When the cases of microcephaly started to soar last month, doctors noticed they coincided with the appearance of the Zika virus in Brazil. They soon discovered that most of the affected mothers reported having Zika-like symptoms during early pregnancy – mild fever, rash and headaches.

On November 28, Brazil’s Health Ministry announced that during an autopsy it had found the Zika virus in a baby born with microcephaly, establishing a link between the two.

“This is an unprecedented situation, unprecedented in world scientific research,” the ministry said on its website.

Research continues to determine if Zika actually causes microcephaly and further establish an association.

Initially concentrated in northeastern Brazil, many cases of microcephaly have now been detected in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo to the south, fueling fears across the country.

Patricia Compassi, from Sao Paulo state, has received an outpouring of support and sympathy on social media after she opened up on national television about her son Lorenzo, born with microcephaly in November.

“It’s been very difficult because initially the ultrasounds were normal,” she told Globo TV in an interview. Early in her pregnancy, she woke up with a rash all over face and achy joints – symptoms that doctors initially attributed to a food allergy and now associate with Zika.

Toward the end of her term, doctors determined her baby would be born with microcephaly.

“There are days that I cry, but just looking at him gives me strength,” she said.

Where Zika came from and where it can go

Zika fever was first discovered in Uganda in the 1940s and has since become endemic in parts of Africa. It also spread to the South Pacific and areas of Asia, and most recently to Latin America.

It was detected in Brazil early this year. Some doctors believe tourists from Asia or the South Pacific introduced it during the 2014 World Cup.

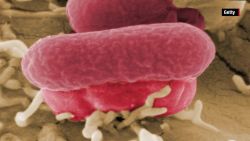

There are concerns it could continue to spread north, but at this point, the virus is known to be transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which thrives in tropical climates. In the United States that type of mosquito is only found in small numbers in Texas, Florida and Hawaii.

Aedes aegypti is the same mosquito responsible for the spread of yellow fever, dengue and chikungunya.

Zika is hard to detect, and there often aren’t any symptoms. Brazil’s Health Ministry says there have been anywhere between a half million and 1.5 million cases in the country in the latest outbreak.

Both the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization have issued alerts in relation to the outbreak of Zika in Brazil and other countries in Latin America.

Federal and local governments have ramped up efforts to combat the Aedes aegypti mosquito and encouraged people – especially pregnant women, to lather on insect repellant and stay indoors.

In Rio de Janeiro, the host city for the 2016 Olympics, officials said they have already made more than 9 million house visits to eradicate the stagnant pools used as a breeding ground for mosquitoes and are monitoring 391 pregnant women who are suspected of having Zika infections.

With the hot, rainy summer just beginning, the concern is Brazil could see a big spike in Zika. And while it could take months or even years before researchers determine if mosquitoes are really to blame, they are encouraging families to avoid risks and hold off on those pregnancies.