Editor’s Note: The story was first published in October and has been updated to reflect the latest developments.

Story highlights

Tensions have ratcheted up in in the South China Sea.

China has a long history of maritime disputes with its South China Sea neighbors

Dotted with small islands, reefs and shoals, the South China Sea is home to a string of messy territorial disputes that pit multiple countries against each other.

China’s “nine-dash line” – its claimed territorial waters that extend hundreds of miles to the south and east of its island province of Hainan – abut its neighbors’ claims and, in some cases, encroach upon them.

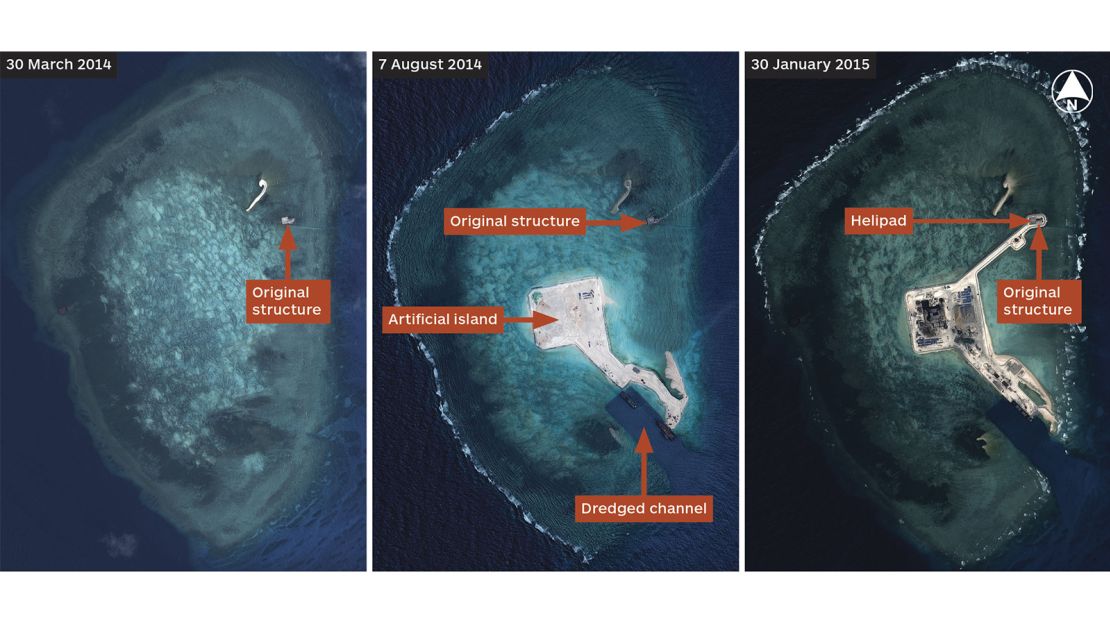

Tensions have ratcheted up as China has reclaimed land in massive dredging operations, turning sandbars into islands equipped with airfields, ports and lighthouses.

Beijing has also warned U.S. warships and military aircraft to stay away from these islands.

Who claims what?

Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam all dispute sovereignty of several island chains and nearby waters in the South China Sea – with rival claims to the Chinese interpretation.

The Paracel Islands have been controlled by China since 1974 but they are also claimed by Vietnam and Taiwan. Tensions flared in 2014 when China installed exploratory oil rigs in the vicinity.

The situation is more complicated in the Spratlys, which Beijing calls the Nansha islands.

The archipelago consists of 100 smalls islands and reefs of which 45 are occupied by China, Malaysia, Vietnam or the Philippines.

All of the islands are claimed by China, Taiwan and Vietnam, while parts of them are claimed by the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei.

China is actually relatively late to the party when it comes to occupying territory in the Spratly archipelago, starting its occupation of reefs and islands in the area in the 1980s.

Taiwan first occupied an island in the Spratlys after World War II, and the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia followed suit, and all have built outposts and airstrips on their claimed territory, according to Mira Rapp-Hooper, a Senior Fellow in Asia-Pacific Security Program at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS).

READ: Washington ‘not provoking’ China

What’s China been building?

In early 2014, China quietly began massive dredging operations centering on the seven reefs it controls in the Spratly Islands – Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, Mischief Reef, Cuarteron Reef, Gaven Reef and Hughes Reef.

According to the U.S., China has reclaimed 3,000 acres since the beginning of 2014.

Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines and Taiwan have also reclaimed land in the South China Sea, but their land grab – the U.S. says approximately 100 acres over 45 years – is dwarfed by China’s massive, recent buildup.

In September 2015, during his trip to Washington, President Xi Jinping said China wouldn’t “militarize” the islands but is building three airstrips that analysts believe will be able to accommodate bombers, according to satellite images analyzed by the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

China has had a military presence on Woody Island, in the Paracels, for half a century and in February deployed surface-to-air missiles and fighter jets on the island.

The Philippines, which lies geographically closest to the Spratlys, has troops stationed in the area, as do other claimants. There are no indigenous inhabitants.

How has the U.S. responded?

The U.S. government takes no position on the territorial disputes in the South China Sea but it has called for an immediate end to land reclamation.

It also sails and flies its assets in the vicinity of the reclaimed islands, citing international law and freedom of movement.

In May 2015, it flew over man-made islands in the Spratlys with a CNN crew on board, triggering repeated warnings from the Chinese navy.

In October, it sent a warship, the USS Lassen, to within 12 nautical miles of Subi Reef. It conducted a similar Freedom of Navigation (FON) operation in January 2016.

“We will fly, sail and operate anywhere in the world that international law allows,” a U.S. defense official told CNN in October.

“U.S. Freedom of Navigation operations are global in scope and executed against a wide range of excessive maritime claims, irrespective of the coastal state advancing the excessive claim,” the official added.

What’s China’s stance?

China says both the Paracels and the Spratlys are an “integral part” of its territory, offering up maps that date back to the early 20th century.

It defends its right to build both civil and defensive facilities on the islands it controls.

Beijing also says it upholds the right of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea but Foreign Minister Wang Yi warned in March 2016 that this didn’t equal the “freedom to run amok.”

China says its control over the disputed waters is justified because it was the first to discover them.

“China was the earliest to explore, name, develop and administer various South China Sea islands. Our ancestors worked diligently here for generations,” Wang said.

“History will prove who is the visitor and who is the genuine host.”

What does international law say?

International maritime law doesn’t accord 12 nautical miles of “territorial waters” to artificial islands – only natural features visible at high tide.

Nor does reclaimed land qualify for a 200 nautical mile “exclusive economic zone (EEZ),” which gives a country special rights such as over exploration of the sea bed and fishing.

Before China’s frenzy of land reclamation, both Subi and Mischief reefs were submerged at high tide, while a sandbar was visible at high tide at Fiery Cross Reef.

In 2013, the Philippines filed a case with the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, seeking a ruling on its right to exploit the South China Sea waters within the exclusive economic zone of the islands and reefs it occupies in the South China Sea.

On July 12, 2016, the court found in favor of the Philippines and said that there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights over the region.

What’s at stake here?

A key route for shipping, $5 trillion in ship-borne trade is thought to pass through the waters annually.

The area is also thought to be rich in natural resources and some areas, particularly around the Malaysian coast and off Vietnam have proven oil and gas fields with billions of barrels of oil and gas equivalent.

The dispute is central to China’s position within the region and globally and it attaches huge importance to maintaining control over islands that it claims as its “indisputable sovereign territories.”

The current posturing in the area has led to heightened tensions between the world’s preeminent military powers, and in May 2015 former CIA Deputy Director Michael Morell told CNN that the confrontation indicates there is “absolutely” a risk of the U.S. and China going to war sometime in the future.

CNN’s Steven Jiang in Beijing and Euan McKirdy in Hong Kong contributed to this report