Editor’s Note: CNN columnist John D. Sutter is reporting on a tiny number – 2 degrees – that may have a huge effect on the future. He’d like your help. Subscribe to the “2 degrees” newsletter or follow him on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. He’s jdsutter on Snapchat.

Story highlights

Join a live Facebook chat with John Sutter at 12 p.m. ET on Saturday

Sutter: December climate talks in Paris could yield real results

We’ve learned to be pessimists about climate change.

Every so often, we hear news about world leaders meeting in some exotic-sounding location – Copenhagen, Lima, Durban, Kyoto – to try to hammer out an agreement to curb heat-trapping gases. We know the stakes are huge – nothing short of the fate of this planet – but it’s become difficult to expect much out of diplomacy.

The meetings have been organized around a wonkish treaty called the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or, you know, U.N.F.C.C.C. for short. They’re attended by pretty much every country in the world. Yet all, so far, largely have failed to really put the brakes on climate change – to stop us from careening toward 2 degrees Celsius of warming, which is regarded as the benchmark for dangerous, unmanageable climate change.

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol, for instance, was signed but never ratified by the United States, and even global sweetheart Canada pulled out and failed to meet its pollution targets. More recently, in 2009, talks in Copenhagen, Denmark, amounted to “a sort of climate wish list,” Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker.

We can’t throw out that frustrating history, of course.

But we can and should do our best to shake it off, Taylor Swift-style.

World leaders are set to meet again 100 days from Saturday. This time in Paris. And, this time, against all odds, there’s ample evidence things finally will be different.

The Paris talks are called COP21 in U.N.-speak, for the 21st meeting of the Conference of Parties. That means this is the 21st time we’ve done this – gathered the entire world and tried to address the global climate crisis on something resembling the scale science says is required.

I’m hopeful that the 21st time’s the charm.

It’s true that a Paris agreement probably will fall short, on its own, of the international community’s stated goal of halting warming at 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit). People following the talks closely tell me that meeting the 2 degrees goal in Paris would be unrealistic. (“That’s not going to happen,” said Nathaniel Keohane, vice president for international climate at the Environmental Defense Fund, for example). But these talks, which aptly, if ominously, have been called “our last hope” for climate action, must be met with bold optimism.

“The window for significant progress on climate is only open every once in a while,” said Jennifer Morgan, global director of the climate program at the World Resources Institute.

“And it’s open – it’s opening – right now.”

Here are five reasons for optimism ahead of the talks.

1. Countries already are pledging major pollution cuts

This U.N.F.C.C.C.’s COP21 meeting in Paris is, in part, taking a bottom-up approach to negotiation. That means that rather than hashing everything out at the actual meeting in December, the big countries are deciding, now, how much climate pollution they will agree to cut. This leaves other issues on the table in Paris but gives negotiators more of a starting point than has been common in the past.

The United States, for example, has announced that it will cut heat-trapping pollution 26% to 28% below 2005 levels by 2025. China will peak its carbon dioxide pollution by 2030. The European Union is pledging even deeper cuts: at least 40% reduction in emissions below 1990 levels by 2030.

Maybe that all looks like numbers soup, but the point is this: The countries are showing their cards, and they’re doing that now. That’s part of what makes an agreement of some sort “inevitable” in Paris, said Jake Schmidt, international program director at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“In Copenhagen (in 2009), frankly, most of the big emitters announced the targets days before the conference, (and there was) not time to digest them and figure out what it meant for the agreement.”

This time, everyone knows where to start the process.

2. China and the United States are playing ball

I recently spent a week in Woodward, Oklahoma, which is one of the most climate-skeptical places in the United States. A common refrain there: It doesn’t matter what the United States is doing because China has the dirtiest air in the world and it doesn’t care at all about climate change.

Conclusion: Why should we bother if they don’t?

But that logic is it is based on “a very dated perspective of the world,” said Schmidt, from the Natural Resources Defense Council. “China has become the biggest market for renewable energy technology in the world,” he told me. Despite still being the world’s biggest carbon polluter, “last year (China) added more solar than the entire U.S. capacity for solar to date.”

That China and the United States – two of the world’s biggest economies and biggest polluters – have both made real pledges to move away from fossil fuels is hugely significant.

In the United States, President Barack Obama recently announced the Clean Power Plan, which aims to use the U.S. government’s regulatory authority to curb pollution from coal-fired power plants.

“It really bends the curve” in global emissions, said Bill Hare, founder and CEO of Climate Analytics, a nonprofit that tracks pollution reduction pledges against the 2 degrees goal. “That is new.”

In November, China and the United States announced an agreement to curb carbon pollution. That “watershed moment” shows that “increasingly, climate is going to be an area of cooperation between China and the U.S,” said Keohane, from the Environmental Defense Fund.

A decade ago, such cooperation would have been unimaginable.

3. The 2 degrees goal is still in reach (barely)

The point of these negotiations is to avoid 2 degrees Celsius of warming.

That threshold is measured since the industrial revolution, and it may be disheartening to hear that humans already have helped warm the climate by 0.8 degrees Celsius to date.

To stop warming short of the 2 degrees mark, leading scientists say, the world needs to be carbon neutral by 2050, meaning no net human emissions of carbon dioxide, said Morgan, from the World Resources Institute. Climate pollution also needs to peak around 2020 and then start declining.

That’s five years from now.

And we’re not on that trajectory.

Current pollution reduction pledges for the Paris agreement put the world on a much more dangerous path, one leading to an expected 2.9 to 3.1 degrees Celsius of warming, according to the Climate Action Tracker, which measures the impact of the Paris pledges. (Without those pledges, the situation would be much worse, with global temperatures expected to rise 3.6 to 4.2 degrees, the tracker shows).

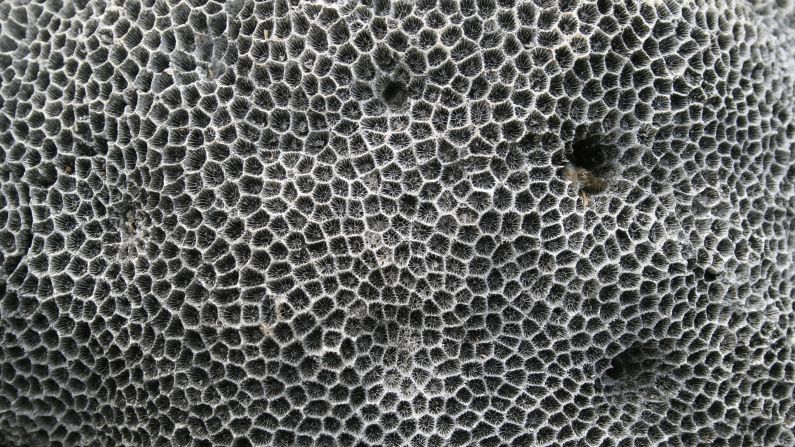

Two degrees of warming, or more, could be catastrophic, sinking low-lying island nations, causing mass extinctions, greatly exacerbating drought and decreasing the availability of fresh water in key areas of the globe.

But the Paris agreement could still make it possible for the world to get on a path to 2 degrees.

“It’s clear to everyone the pledges are not going to be sufficient at this step to limit warming below 2 degrees. There are no analyses that will contradict that,” said Hare, of Climate Analytics. “One needs to ask the question: Well given that, is it still possible to get to 2 degrees? I think it’s clear it still is. …”

To do so, people closely following the negotiations told me, the Paris agreement needs to accomplish a few things: It should send a strong signal that the world is moving away from a fossil fuel economy, and won’t turn back; it needs to ensure that pollution pledges only will get stronger over time; it needs to ensure that countries meet again, as soon as five years from now, to ratchet up their commitments; and it needs to require countries to report on their progress transparently, and for those reports to be independently verified.

“What’s most important is establishing the foundation for meaningful, long-term action,” Robert Stavins, director of the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, told me via email.

“This is as much about the road through Paris as the road to Paris,” said Morgan, from the World Resources Institute. “Solving this problem is a multi-decadal effort. The international agreement is an important piece of that, but it’s not the silver bullet.”

4. Hundreds of thousands are demanding action

Rallying to stop climate change

Last year, I was one of an estimated 300,000 people who marched in New York for action on climate change. That sort of grassroots mobilization on this issue is unheard of – and organizers are going to try to replicate it for the United Nations climate talks in Paris, which start on November 30.

People are demanding action. They’re calling on universities and nonprofits to divest from fossil fuel interests, greening their portfolios and dealing a symbolic and financial blow to coal. They’re telling governments that deadly, dirty air is incompatible with economic growth. And they’re raising their voices to demand that world leaders put us on track to halt warming short of 2 degrees.

There’s reason to believe this enthusiasm with infiltrate the stodgy climate negotiations in Paris.

“What’s going to drive reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in China? It’s not going to be whether the (Paris) treaty is legally enforceable or not,” said Keohane, from the Environmental Defense Fund.

“It’s going to be whether its people demand cleaner air.”

They are, and it appears that China – and others – are finally listening.

5. The stakes are too high to give up

The difference between 2 degrees and 4 degrees of warming may not sound like much, but consider this: The World Bank has said there is “no certainty that adaptation to a 4-degree world is possible.”

“A 4-degree Celsius world is likely to be one in which communities, cities and countries would experience severe disruptions, damage, and dislocation, with many of these risks spread unequally,” the World Bank says in a November 2012 report. “It is likely that the poor will suffer most and the global community could become more fractured, and unequal than today. The projected 4-degree warming simply must not be allowed to occur – the heat must be turned down.”

Even turning the heat up by 2 degrees could be seen as too costly.

Take the Marshall Islands. I traveled there this year to meet people who are being displaced by frequent floods in those low-lying Pacific islands. Some experts predict that the entire country, which is made up of atolls and islands barely above sea level, will flood at 2 degrees of warming.

Global warming matters too much to give up hope.

It’s possible to reach this target, but Paris must send the world clear signals.

“The next step needs to be bigger and the subsequent step bigger, and then we can get into the 2 degree pathway, or below that pathway,” said Hare, of Climate Analytics. “It’s disappointing we’re going to be below the 2 degree pathway at Paris, but i don’t think that’s reason to give up on that target.”

“I’m concerned,” he said, “but not pessimistic.”

Neither am I. We owe it to the planet to remain optimistic.