Story highlights

More than 60,000 women diagnosed with Ductal carcinoma in situ annually

DCIS, known as Stage 0, does not always result in breast cancer

More than 60% of all women over 40 in the United States have had a mammogram in the past two years. And 20% of mammograms detect something called ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS – also known as Stage 0 breast cancer.

According to the American Cancer Society, more than 60,000 cases of DCIS are diagnosed every year. But it doesn’t mean breast cancer.

DCIS are abnormal cells found inside the milk ducts of the breast. They can look like invasive breast cancer cells, but they haven’t spread into the breast tissue – and in some cases may not. Doctors treat DCIS one of three ways: with a lumpectomy, removing the masses themselves; lumpectomy and radiation; or removing the breast altogether with a mastectomy.

However, a new analysis published in this week’s Journal of American Medical Association Oncology questions the necessity of some of these treatments. Tracking more than 100,000 women diagnosed with DCIS for 20 years, Dr. Steven Narod, of the Women’s College Research Institute in Toronto, and his colleagues found that women treated for DCIS had a similar chance of dying from breast cancer as those who had never been diagnosed. All the women were part of the National Cancer Institute’s SEER program, a database of cancer patients in the United States.

Not only did women who were treated have similar chances of dying from breast cancer as those who hadn’t been treated, but also the type of treatment didn’t seem to make much a difference. “The three treatments have about the same outcomes,” said Narod.

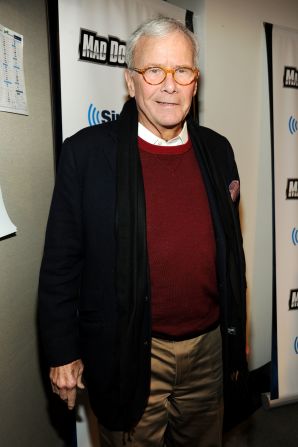

It raises the question of whether we are being overly aggressive with our treatment of DCIS, said Dr. Otis Brawley, chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society. “Unfortunately, this is something repeated over and over in medicine.” Doctors treat aggressively, then over the next 40, 50, 80 years find out that we didn’t need to be nearly as aggressive.”

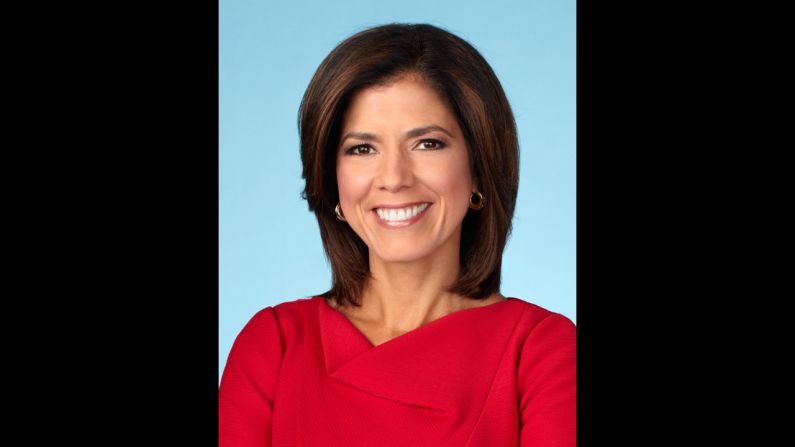

Joni Avery, spokesperson for the Susan G. Komen foundation, was more cautious. She said, “There is potential for ‘overtreatment’ of cases of DCIS. However, we currently do not have the ability to definitively determine which cases of DCIS are ‘high risk’ and which aren’t.”

Dr. Laura Esserman, of the University of California San Francisco, said to stop thinking of DCIS as a single condition to help determine treatment. “The biology is varied. Some are low risk and some are high risk. We need to understand it and offer different options.” Risk factors to consider are age, family history, and ethnicity.

But instead of questioning treatments, Dr. Larry Norton, of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, said the analysis was a testament to the success of treatments. “Maybe the treatment brought them back to the general population risk.”

Narod also pointed out that treatment provides more than just physiological benefit, but also psychological relief. In his analysis, women who were treated with lumpectomy and radiation reduced their risk of recurrence from 4.9% to 2.5%. Those who underwent a mastectomy further reduced their chance of recurrence to 1.3%. “The chances diminish by half with radiation, and are almost eliminated with mastectomy. People want to avoid it. Quality of life seems to be improved if recurrence was removed,” said Narod.

“If you’re going to have this treatment to reduce recurrence, I would say get the mastectomy. The better of those two treatments, mastectomy involves a tremendous amount of mental relief.”

Brawley advised caution. “Take a deep breath and slow down. Learn about DCIS treatment. Talk to several doctors and interview them about treatment. But one does not need to run in and have both breasts removed just because [of] DCIS.”