Blur are currently touring their Hong Kong-inspired new album, The Magic Whip. It’s the British band’s first album as a four-piece in 16 years, and fans and critics alike are piling on the praise. Rolling Stone called it “quixotic and seductive in its modern searching” and Pitchfork opined that in some moments, Blur’s forte in the “identification and subversion of listener expectations” has re-emerged, “untarnished by the passage of time.”

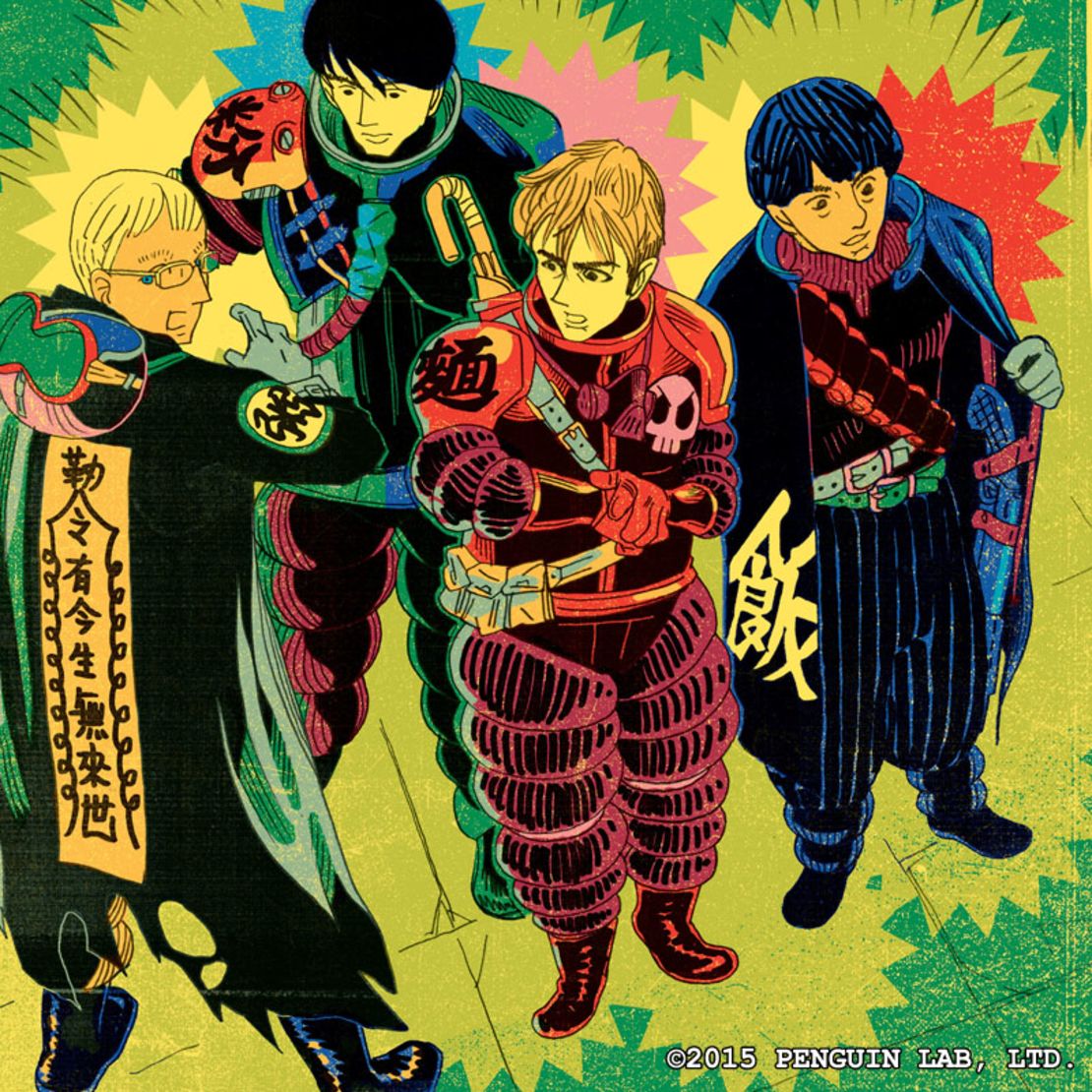

Artist Kong Kee, of Hong Kong-based animation studio Penguin Lab, was one of the first people to listen to the album before its late April debut. The band, which recorded part of the album in the East Asian island city, commissioned Kong to illustrate a special comic book that could be both “retro” and “edgy” to accompany the record’s release.

He was allowed to preview each track just once for inspiration. Kong recalls: “When I heard the songs, I had this feeling that they are still Blur. The energy, the way they observe society, it still feels young and creative. You can imagine Damon walking around the city, having many ideas.”

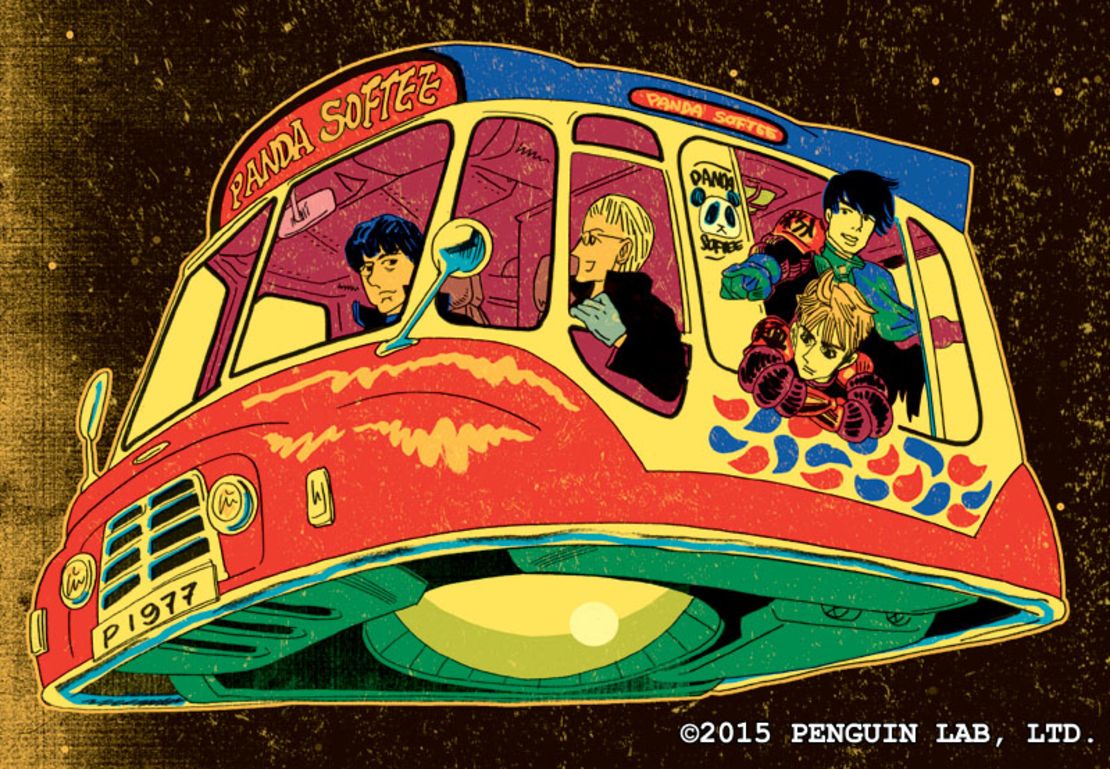

Instead of walking, Kong has illustrated singer Damon Albarn, along with guitarist Graham Coxon, bassist Alex James and drummer Dave Rowntree flying in an ice cream truck, as they adventure through Hong Kong old and new.

Kong expertly captures the city’s unique mix of tradition and modernity, showcasing the density of old apartment blocks, the “ding-ding” tram, a fishing village, a performance of Cantonese opera, and the recent Umbrella Revolution – led by penguins, who feature heroically in Kong’s other works. “I wanted Blur to see different sides of Hong Kong and to get in touch with Hong Kong people,” says Kong.

While Hong Kong comics aren’t as well known internationally – as American and Japanese forms are – they have had an important history. During the Second World War, waves of Chinese artists fled to Hong Kong from Japanese occupied China. This led to the creation of numerous dissident propaganda comics – penned in Hong Kong and distributed throughout China – in support of the allied war effort.

After the war, the artists continued to play an active role in Hong Kong life, with comics becoming a popular source of entertainment, particularly among blue-collar workers – who were largely illiterate at the time. Later, as the industry developed into the 1980s, comics were mass-produced by large production houses.

But the mainstream focus on subjects such as martial arts and Kung Fu of recent decades is shifting. Contemporary artists are becoming more diverse in their choice of subject matter, choosing to concentrate instead on the nuances of everyday life.

“We have this strong sense to try to use comics to build our identity, to say to the world what we look like. This is unlike the older generation, who came from Mainland China and used Hong Kong as a stepping stone. Young people grew up after the 1997 handover, and we feel that Hong Kong is our home, and we have our own story to tell,” says Kong.

Since the early 2000’s, the comic industry worldwide has taken a hit in sales and demand, with the onset of competing forms of gaming and entertainment. Nowadays, Hong Kong comic book artists rely on crowd funding and digital forms of distribution, rather than publishing houses.

This has prompted the Hong Kong government to find ways to support the emergence of indie artists and to preserve the art form, particularly at time when Hong Kong politics and identity are at a precipice.

Connie Lam, the executive director of the Hong Kong Arts Centre, explains: “Over the past few years, Hong Kong has faced important issues and artists are using comics as medium to voice their dissent.”

In 2013, Lam helped to establish Comix Home Base, a platform for artists like Kong to exhibit their work domestically and abroad.

“We treat animation and comics as arts and culture, and not only as a commodity, that way it can last,” says Lam.

For comic book artist Kong, The Magic Whip album evoked feelings of nostalgia – referencing the breakneck pace of the city, its changing demographics, and the furious transformation of its skyline.

“When I kept listening to their album, I have this feeling that I am traveler. The Hong Kong that I’m living in is not the same that I know. The memory is gone, I want to hold it, but it is impossible. I want to use this book to give this space, to stop a moment, to rethink, to feel, what we have lost, and what we still have.”