Story highlights

Discovery supports a theory that the building blocks of life could have been brought to Earth by comets

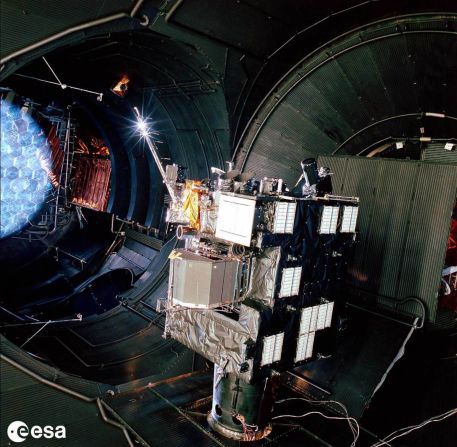

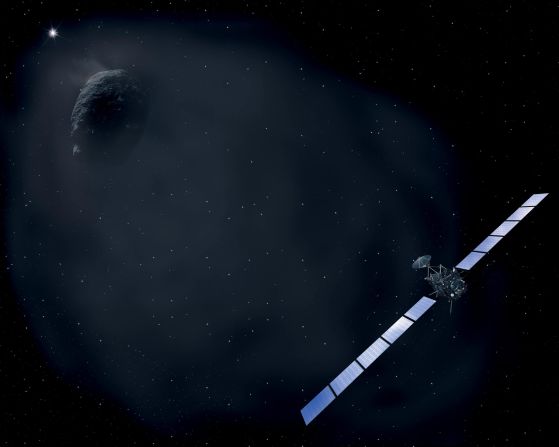

Philae lander bounced onto the surface of comet 67P in November 2014

ESA says the mission has been extended to next year when the Rosetta orbiter will most likely land on the surface of the comet

Could life on Earth have been kick-started by a comet strike? A startling discovery by the Rosetta comet-chasing mission has added fresh evidence to suggest that it is possible.

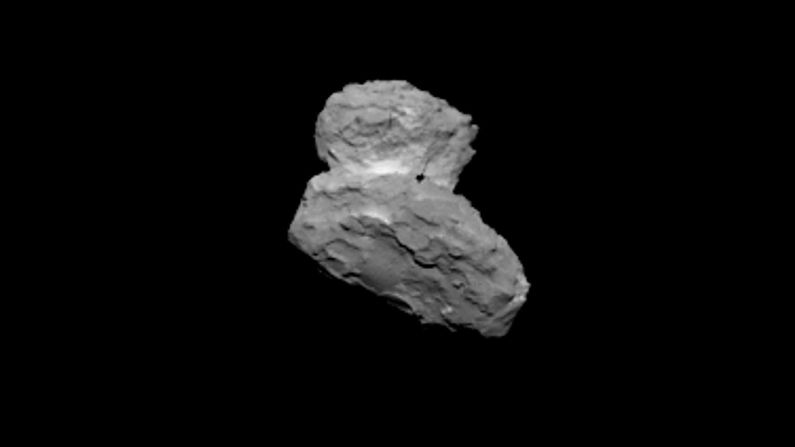

The European Space Agency (ESA), which is leading a consortium that includes NASA, announced that the mission to explore Comet 67P has discovered 16 organic compounds, described as “carbon and nitrogen-rich.”

The agency says on its website that the discovery, made by the Philae lander includes four compounds that have never before been detected in comets.

And it adds that some of the compounds “play a key role in the prebiotic synthesis of amino acids, sugars … the ingredients for life.”

“For example, formaldehyde is implicated in the formation of ribose, which, ultimately features in molecules like DNA.

“The existence of such complex molecules in a comet, a relic of the early Solar System, imply that chemical processes at work during that time could have played a key role in fostering the formation of prebiotic material,” it says.

Commenting on the findings, lander system engineer Laurence O’Rourke told CNN it was an important discovery.

“If you apply energy to such organic compounds … like a comet hitting a planet … it could lead to the creation of amino acids which make up proteins, which are the basis of life itself,” he said.

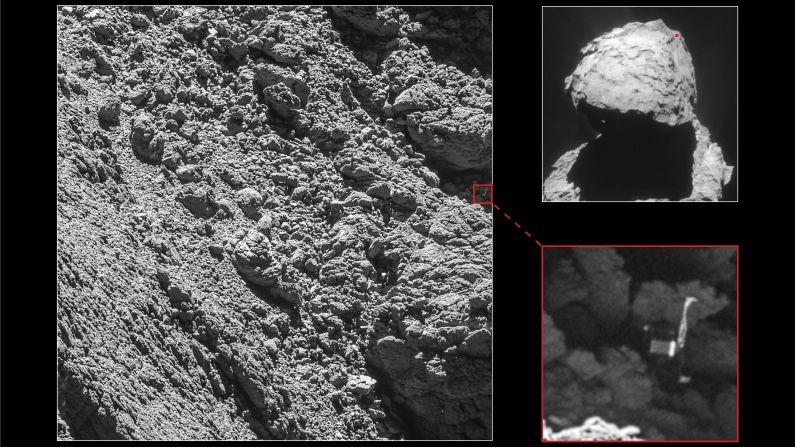

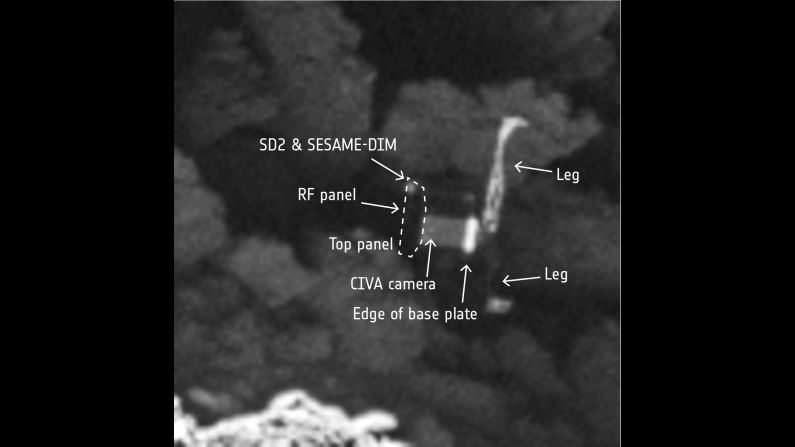

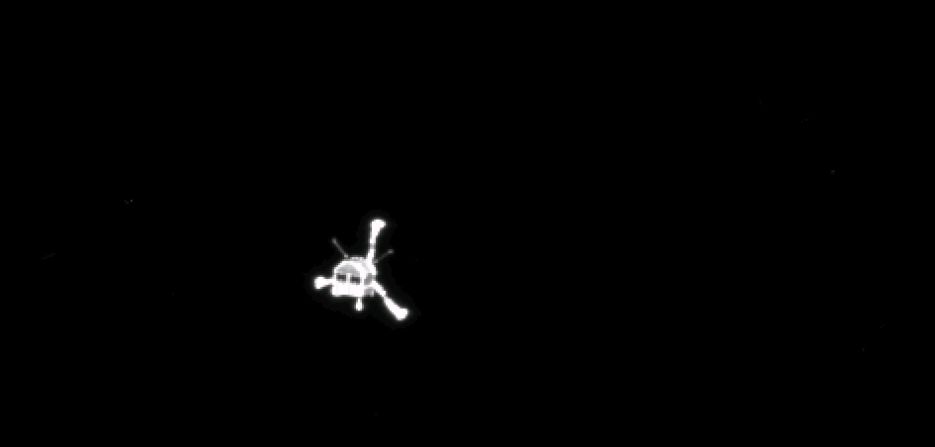

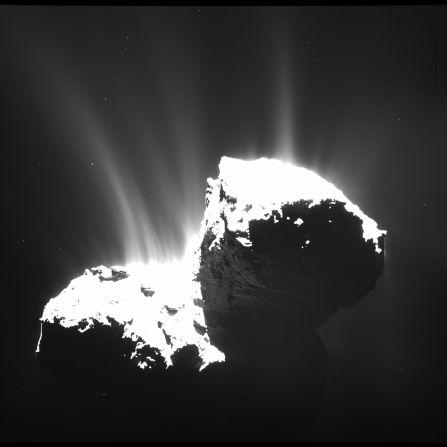

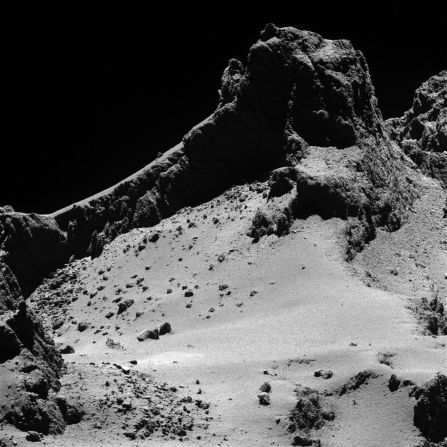

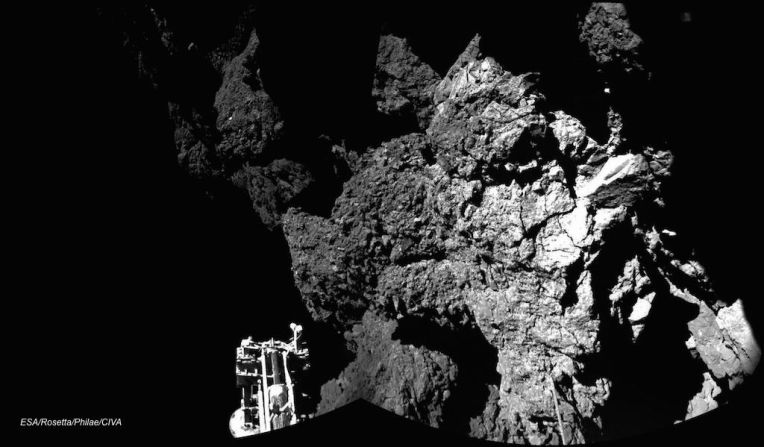

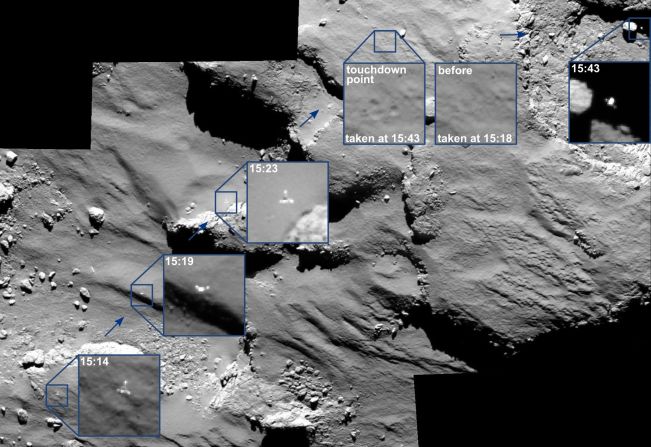

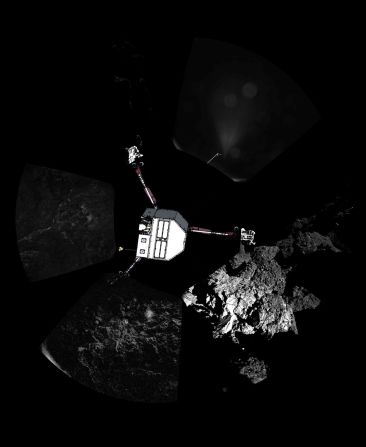

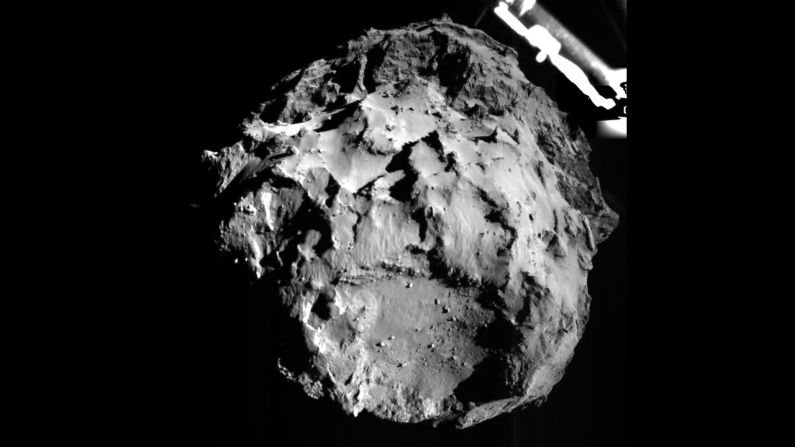

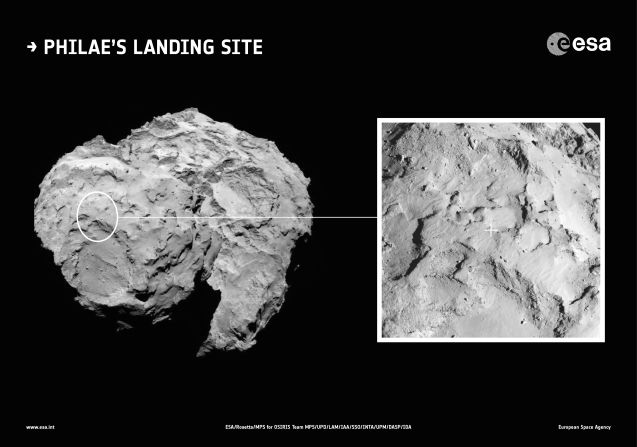

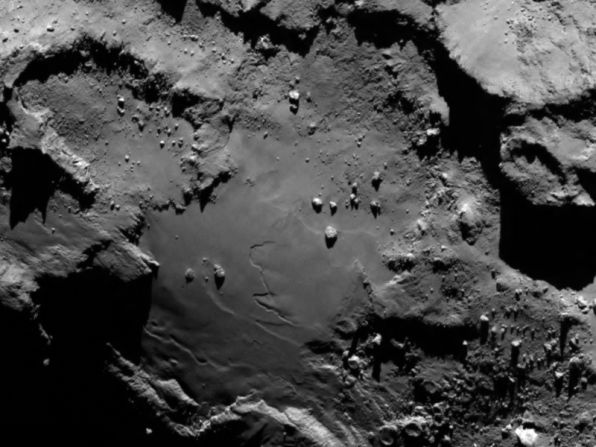

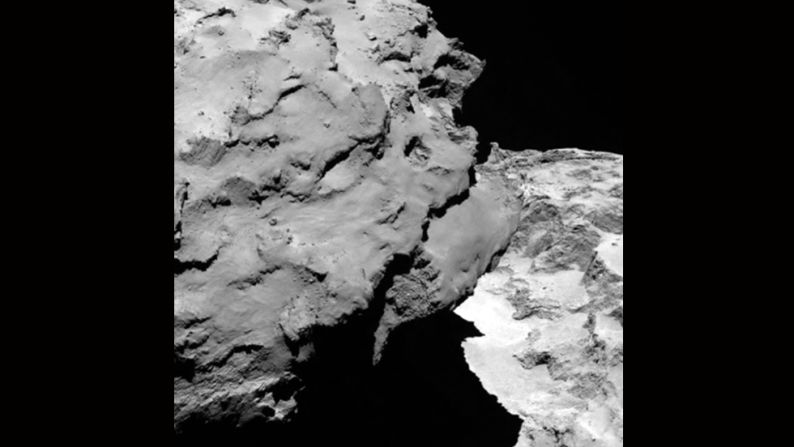

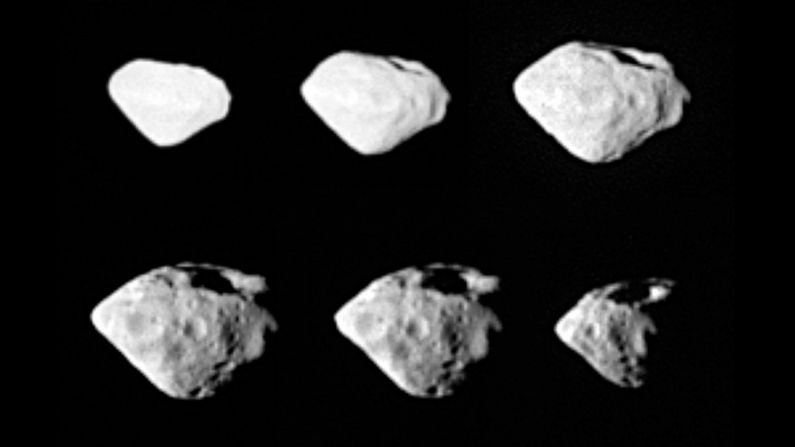

The Philae lander has tantalized mission watchers ever since it bounced across the surface of 67P in November 2014. It was able to take measurements in two locations – once on hitting the surface, and again when it came to rest under a cliff.

The bounce turned out to be a happy accident, as Philae was protected from the scorching sun. In the first hours of its mission, Philae returned the data that has proved to be so exciting.

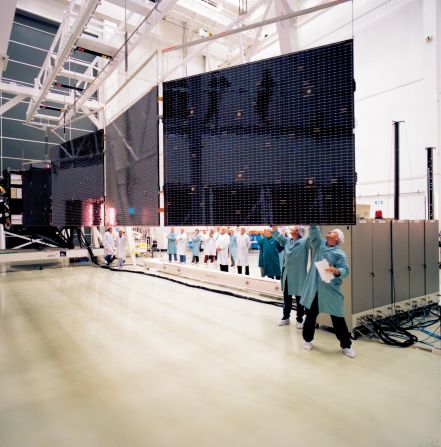

Although contact was later lost when it ran out of power, the probe came back to life and transmitted a signal to the Rosetta orbiter when enough sunlight fell on its solar panels to revive it.

Project scientists knew there were problems with the probe’s transmitters, and contact was lost again in early July. But O’Rourke says that Philae is a “robust machine” and there is hope of getting a new signal.

“There’s no way we can say the lander is dead,” he said.

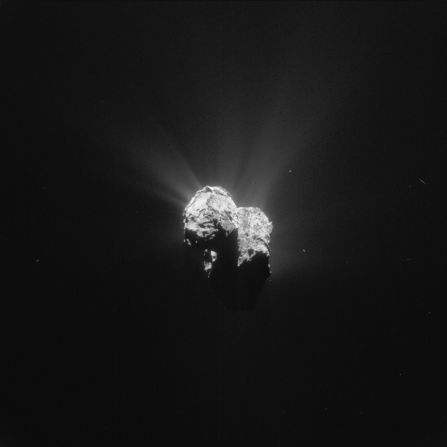

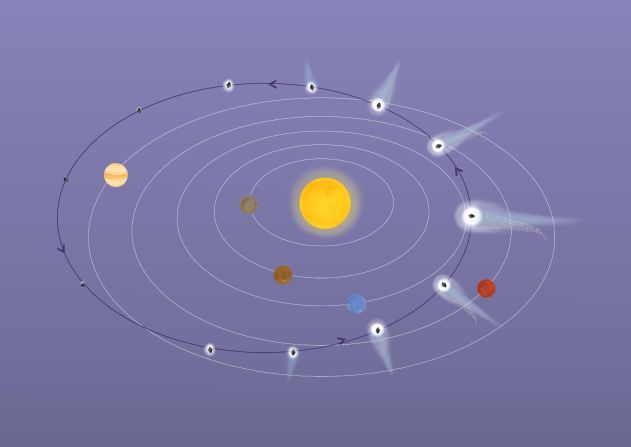

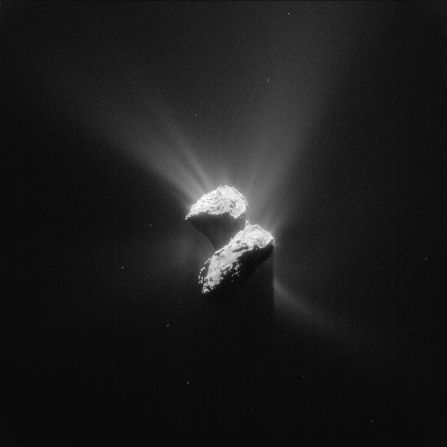

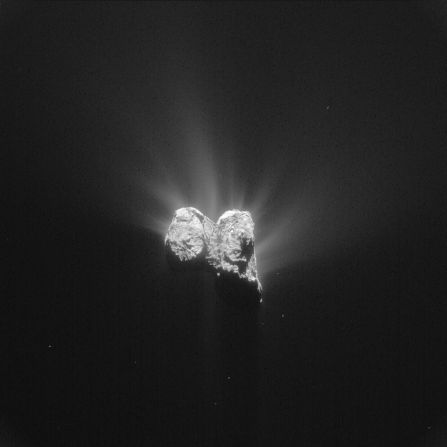

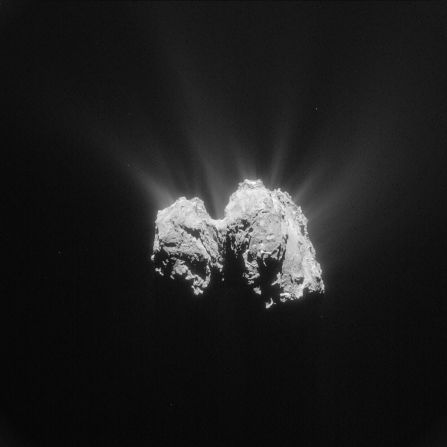

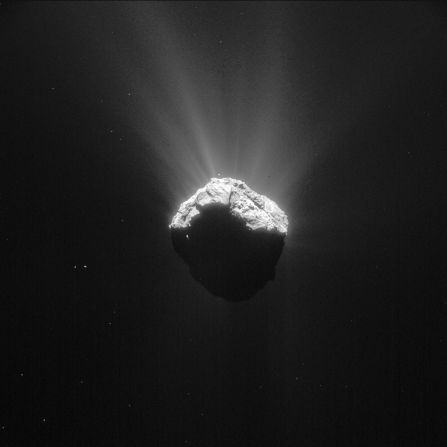

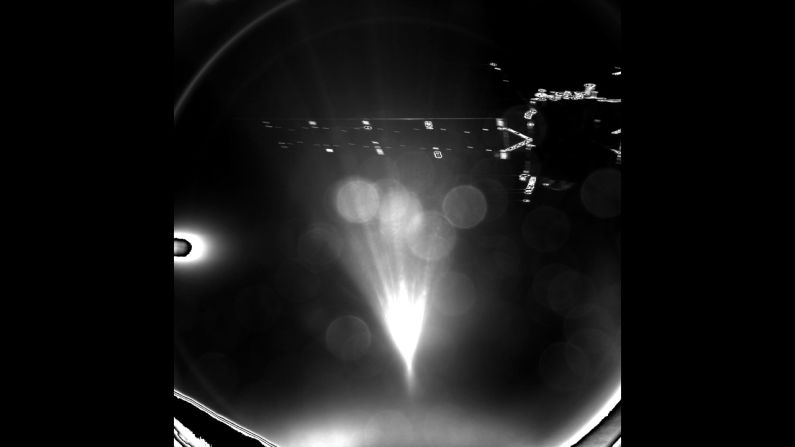

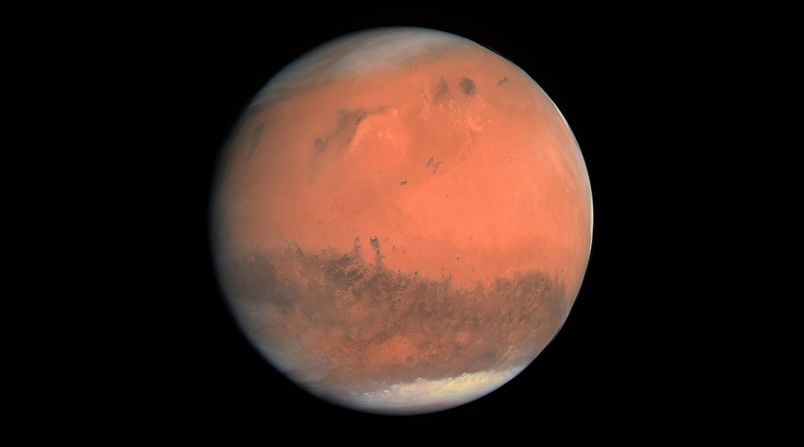

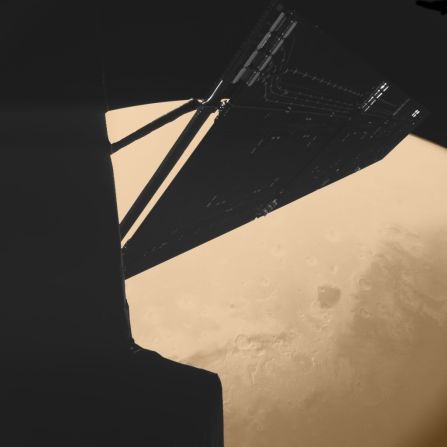

The mission is now approaching an important landmark called perihelion, the point in its orbit where the comet is closest to the sun. Comet 67P and its accompanying spacecraft are traveling at nearly 75,000 miles per hour and will come closest to the sun on August 13 before it swings around and begins its outward journey once again. This comet returns every 6.5 years.

As the comet approaches the sun, increasing solar energy warms up frozen ice, turning it to vapor. The European Space Agency’s website explains that the gases drag away the comet’s dust, appearing as a tail extending sometimes hundreds of thousands of miles into space.

“Perihelion is an important milestone in any comet’s calendar, and even more so for the Rosetta mission because this will be the first time a spacecraft has been following a comet from close quarters as it moves through this phase of its journey around the Solar System,” Matt Taylor, an ESA Rosetta project scientist, said on the mission website.

The mission has now been extended to September of next year, when the Rosetta orbiter will most likely land on the surface of the comet, the ESA says.