In the future, transatlantic flights could be smooth sailing, literally. Rather than slamming down on a runway on the outskirts of a city center, passengers could land on along the coast in a jumbo seaplane.

According to Dr. Errikos Levis, a researcher in the Department of Aeronautics at Imperial College London, seaplanes could be the answer to at least two of modern aviation’s greatest burdens: airport congestion and noise pollution.

“We can use seaplanes to move noise away from population areas and reduce the need to have extensive infrastructure,” he says.

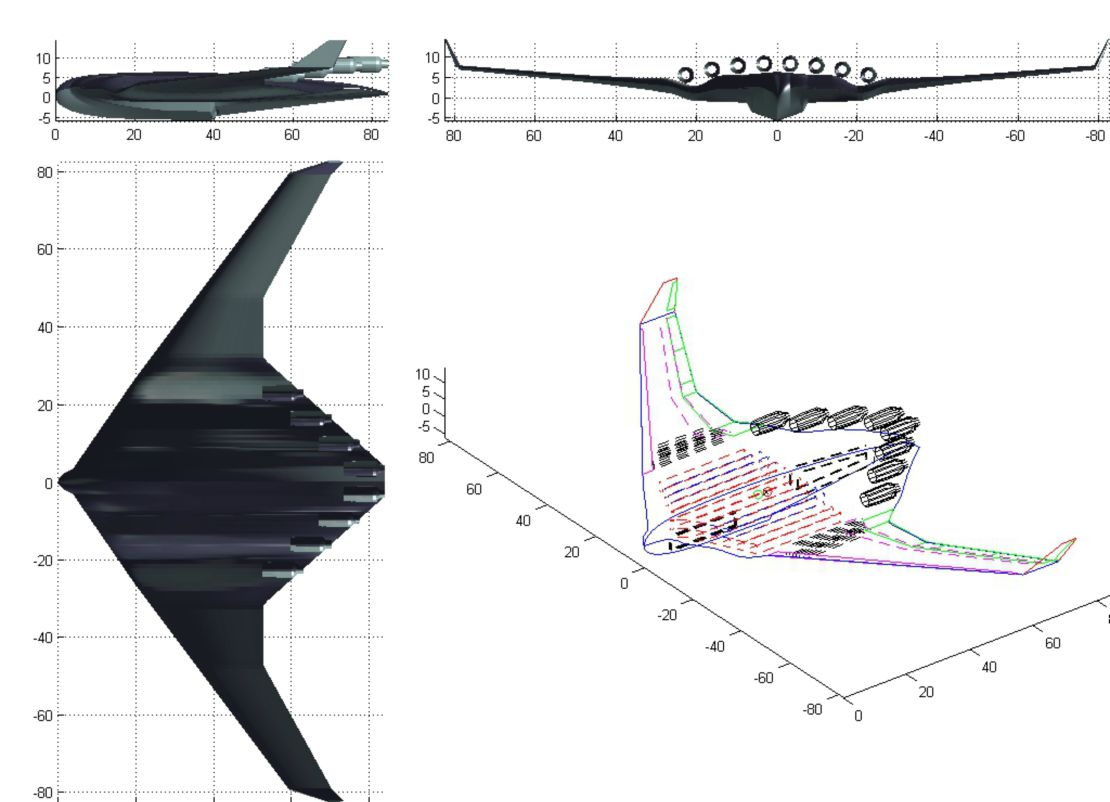

Dr. Levis co-authored a study on the potential of seaplanes as tomorrow’s jumbo, passenger aircraft. Together with Professor Varnavas Serghides, he’s come up with the design of a family of seaplanes that could accommodate anywhere from 200 to 2,000 passengers.

Though theirs is a radically new concept design, seaplanes are in fact a very old idea.

“Seaplane development basically stopped after the mid-40s, because they were substantially less aerodynamically and structurally efficient than land planes,” he says.

Seaplanes, for starters, traditionally demand tip floats, a heavy apparatus that ensures lateral stability on the water’s surface but also increases the plane’s drag penalty by up to 20%. The awkward shape of the aircraft body, particularly the V-shaped hull – which is necessary to help the plane navigate through water – also traditionally added to the drag factor.

Design basics

To reduce the air resistance incurred by the V-shaped stepped hull, the team employed a blended wing body, where the hull sweeps upwards to merge with the underside of the aircrafts’ wings. He also decided to get rid of the tip floats altogether.

“The inboard sections of the wing itself actually provides that lateral stability,” says Dr. Levis.

The engines will also move to the top of the plane, which will help shield them from spray (“A big problem for seaplanes,” says Levis). The move will also deflect noise so that those living underneath a flight path won’t be as affected by the engine’s roar.

The bigger the better?

Dr. Levis doesn’t believe seaplanes would replace land planes, and he notes that they’re still no match in terms of fuel efficiency at smaller sizes.

“We still couldn’t quite beat what the current state-of-the-art land planes consume, especially at smaller sizes,” he admits. At sizes of 800 passengers and above, however, the efficiency is on par and sometimes better than that of current aircraft, he adds, using what he deems conservative assumptions for the aircraft’s final structural weight to determine his calculations.

He also noted that seaplanes wouldn’t be under the same size constraints as landed planes, which are limited due to fixed runway widths. As a result, a 2,000-person seaplane is feasible, and at the larger sizes, a seaplane could even use the more environmentally-friendly hydrogen fuel – something traditional aircraft can’t use as easily since hydrogen takes up four times the volume as Jet-A1 fuel.

“We can’t put passengers underneath the waterline for safety reasons, so what we found is we have a lot of empty space there, which we can use to fit in hydrogen,” says Levis.

Tomorrow’s airplane?

Alas, the seaplane is not likely to take off anytime soon, even though, says Levis, the technology is basically there.

“There’d need to be some research, but it’s not like we’re using anti-gravity! The vast majority of the things we used (to design these planes) are there,” he says. Still, he imagines that if work started on it today, it would take about a decade before the design became a reality.

“What’s really lacking at the moment is the will to try something new,” he says.