Editor’s Note: Every week, Inside Africa takes its viewers on a journey across Africa, exploring the true diversity and depth of different cultures, countries and regions.

Story highlights

Divers found the fossils of extinct giants underwater. They took footage, and it's breathtaking

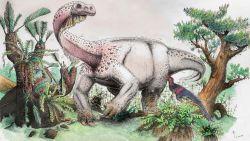

Around 5,000 years ago, the island of Madagascar would have resembled a Sci-Fi novel.

Strange, prickly forests, gorilla-sized lemurs, pygmy hippopotamuses, horned crocodile and elephant birds whose eggs were 180 times the size of what you’d find in your fridge today, all called the African island home – that was until the humans arrived.

“If you went to Madagascar just when human populations were beginning to grow, you’d have found a very different place than what you find today,” says Laurie Godfrey, a palaeontologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Godrey is part of an international team who recently uncovered one the most incredible cache of fossils found on the island to date in three flooded caves. The find is being touted as Madagascar’s largest underwater graveyard.

Adventure wonderland

All three caves – Malaza Manga, Aven and Mitoho – are submerged underneath Tsimanampetsotsa National Park.

Their paleontological potential was first uncovered by Australian diver Ryan Dart. When Dart saw what was down there, he contacted his colleague Phillip Lehman, a diver for the Dominican Republic Speleological Society.

“I figured, worst case scenario, we’d find a great surf spot,” recalls Lehman.

What he found instead were the remnants of a lost world.

“The formations are literally mind-blowing. There are crystallized geological formations coming out of the walls, coming out sideways looking like spaghetti. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

With funding and logistical help from the National Geographic Society, the National Science Foundation and Madagascar National Parks, the group that Lehman ultimately helped form made an initial exploration of the cave, and turned up gold.

‘Clean like chicken bones’

“The materials we found in the caves are almost pristine,” marvels Alfred Rosenberger, a primate palaeontologist at Brooklyn College who Lehman first contacted after his initial dive.

“Just imagine: the bones lying there on the surface and they get trampled by big animals or run over by trucks and crushed. These bones aren’t damaged in any way. They look fresh like chicken bones on the table.”

It is also unusual to find the bones of individual animals so closely grouped together. Usually, says Rosenberger, bones will be separated by several feet, and piecing them together can be a bit of a jigsaw puzzle.

In Mitoho cave, he says they even found two fossa – the catlike carnivore made popular by the “Madagascar” film franchise – on top of each other, surrounded by large deposits of smaller bones.

Rosenberger estimates this was probably a lair.

“We think these guys might have been in the cave on their own, chomping away on something, and something catastrophic, like a flood, took them at the same time,” he muses.

Overlap with humans

Though extinct and unique, the animals uncovered in the caves died out incredibly recently, at least in paleontological terms. Certain signs point to their co-existence with humans – who first inhabited the island in 500 BC.

“We know that we have some (fossils) that are in the region during the human period, because we have introduced species there, like rats and Indian civets, which are not native to Madagascar,” explains Godfrey.

Godfrey and her colleagues believe that human impact probably played a large role in wiping out Madagascar’s indigenous species, though the exact cause can only be guessed at.

“It could have been hunting or habitat modification – for instance after people introduced cattle to Madagascar and started burning areas for agriculture,” she muses. Soon, though, she might have a clearer answer, as her team ultimately tests the recovered fossils and samples.

“We now have ways for getting at the cause of extinction. For example, you can tell a lot about the fire history of an area by measuring the degree of charcoal micro-particles in sediment,” she explains.

Camera: Pietro Donaggio. Extra courtesy Ryan Dart and Patrick Widmann