Editor’s Note: Vital Signs is a monthly program bringing viewers health stories from around the world.

Story highlights

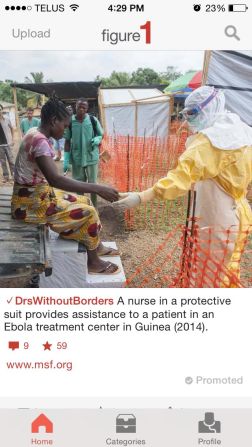

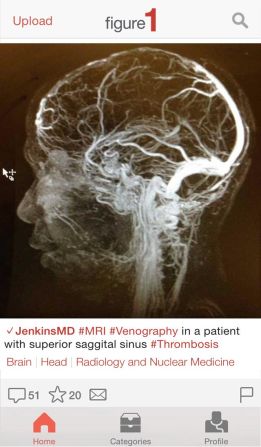

Figure-1 is a medical photo sharing app that lets doctors upload images and scans to aid diagnosis

Identifying information is removed or covered before images are posted to ensure anonymity

The idea is at the foundation of social media channels: Seen something strange? Post it online. The desire to share the unknown, or complex, is a human urge, and no-one knows this better than doctors.

“I’m a very visual learner. Most doctors are … and we like to talk to each other,” explains third-year medical resident Sheryll Shipes of Christus Spohn Hospital Corpus Christi-Memorial, in Texas.

Last year Shipes began using Figure1, a photo-sharing app through which healthcare professionals can share photographs and information about their patients for both learning and diagnosis purposes. “It’s now my medical guilty pleasure,” she adds.

It may ring alarm bells regarding patient confidentiality but founder Josh Landy, an intensive care specialist at Scarborough Hospital in Toronto, Canada, vows that anonymity, ethics and patient approval are at the core of the technology. He says his objective is the sharing of knowledge.

Read: The worms that invade your brain

“People (already) share cases through text and email,” he says.

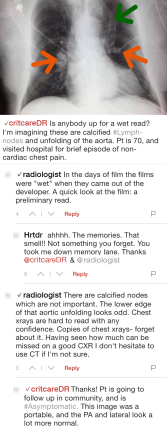

As a medic himself Landy understands the need to seek external opinions when treating a variety of patients. One day, when looking around his hospital unit, Landy realized how commonplace this virtual sharing was among his students as their hands were occupied not with stethoscopes, but smartphones. They were in search of a second opinion – and now they can get third, fourth and fifth opinions in a single click, with his photo-sharing app.

“We looked at how people are using their smart phones,” he explains, having seen many cases being shared between doctors using this medium. “I wanted a way to present all those cases … to create a global knowledge notebook.”

Feedback from the community

Launched in May 2013, Figure-1 enables users to take an image, remove any identifying information, and upload the image for feedback from the community of healthcare users accessing the app. Those not uploading use the app as a learning tool to expose them to conditions and symptoms they may not otherwise see. “It’s medical education,” says Landy.

In developing the app, Landy ensured anonymity would become standard through the removal of any identifying features, names, numbers or case information when images are uploaded. All images undergo additional verification before becoming publicly available and patients must also give their permission for their photos to be shared.

Whilst the general public may have interest in medical images, Landy stresses the importance of targeting mainly those working in healthcare. New users are asked for occupational information upon registering and only healthcare professionals can comment or add pictures.

The app is now available in 19 countries and as of summer 2014 there were 150,000 users, according to Figure-1. The number is expected to be higher today with images in the library being viewed on average 1.5 million times a day. The greatest popularity lies in the continent of origin, with Figure-1 now being used by 30% of U.S. medical students, including Shipes.

“It’s classic medicine, digitized,” says Shipes. Having used Figure-1 religiously over the past year, Shipes readily sings its praises after the app helped her diagnose a patient with an unusual skin disorder causing blisters on certain parts of her body. “I uploaded it to Figure-1 and someone told us exactly what it was,” she says. The condition turned out to be common to Latin America and Asia but rare in the United States. “We would never have known that one.”

Now Landy hopes word will spread even further. “It’s overdue for a tool like this,” he concludes. “I’d like to see it everywhere.”