Editor’s Note: Jeff Yang is a columnist for The Wall Street Journal Online and can be heard frequently on radio as a contributor to shows such as PRI’s “The Takeaway” and WNYC’s “The Brian Lehrer Show.” He is the author of “I Am Jackie Chan: My Life in Action” and editor of the graphic novel anthologies “Secret Identities” and “Shattered.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Students in the massive protests in Hong Kong want representative democracy

Jeff Yang: These protesters may be the most sophisticated and technologically savvy ever

He says Chinese authorities are blocking images and creating apps that trick protesters

Yang: Smartphone a great tool for populist empowerment but it can easily be used against us

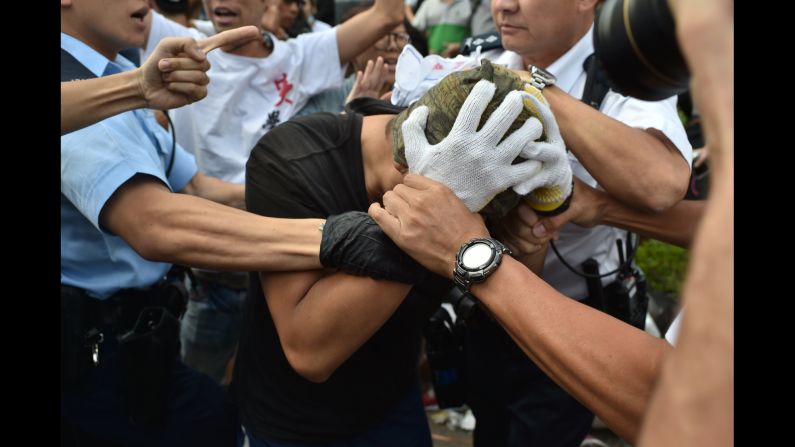

The massive protests in Hong Kong took an ugly turn on Friday when students pressing for representative democracy clashed with opponents, prompting a breakdown of talks aimed at defusing the crisis.

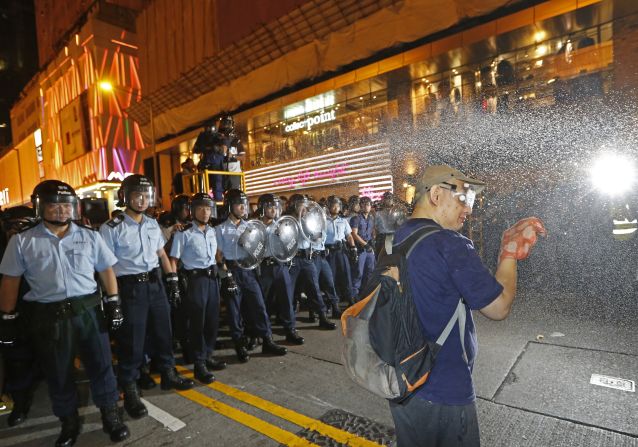

This negativity followed a week of remarkably peaceful civil disobedience in what has been dubbed the “Umbrella Revolution,” after the widely shared image of a man defiantly holding up an umbrella in a haze of police tear gas fired to disperse the tens of thousands of activists crowding the city’s main government and business thoroughfare, the region referred to as Central.

But protesters shrugged off the gas assault as if it had never happened. Behind the barricades, they studied for exams, coordinated the cleanup and recycling of trash generated by the crowd, and jerry-rigged guerrilla charging stations for the voluminous array of devices the demonstrators are using as part of the sophisticated war they’re waging on the virtual front, wielding the digital-age weapons of image feeds, live streaming video and ceaseless social media updates.

The Umbrella Revolution is hardly the first protest to harness the power of technology to coordinate activities and broadcast messages, but it’s almost certainly the most sophisticated.

Andrew Lih, a journalism professor at American University, discussed the infrastructure the activists have adopted in an article for Quartz, a system that incorporates fast wireless broadband, multimedia smartphones, aerial drones and mobile video projectors, cobbled together by pro-democracy geektivists like the ad-hoc hacker coalition Code4HK.

Given this remarkable show of force by the crowd under the Umbrella, it’s not surprising that Beijing has moved quickly to prevent transmissions from reaching the mainland, blocking Chinese access to Instagram, where images and videos from the demonstrations and police crackdowns are regularly being posted, and banning all posts on popular messaging sites like Weibo and WeChat carrying keywords that refer to the protests.

Activists have fought back by downloading the peer-to-peer “mesh messaging” app FireChat — which allows communication among nearby users even when centralized mobile services are unavailable by linking smartphones directly to one another via Bluetooth and wifi — in the hundreds of thousands, and by creating an elaborate system of numerical hashtags to stand in for forbidden terms.

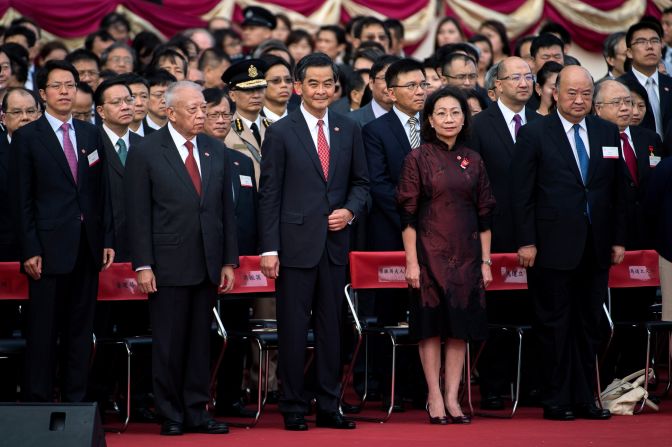

For example, #689 is the codename for Hong Kong chief executive C.Y. Leung, referring to the number of votes he received in his selection as the region’s highest government representative, a scant majority of the 1,200 members of the the Communist Party-approved nominating committee. #8964 references Beijing’s brutal June 4, 1989, crackdown on student democracy activists in Tiananmen Square, which casts a looming shadow over the Occupy Central demonstrations.

These strategies seem to have prompted the Chinese authorities to resort to new and more insidious tactics. Links — seemingly posted by Code4HK — have begun popping up on social media, inviting users to download a new app that allows for secure coordination of protest activities.

Instead, clicking the link downloads a Trojan horse that gives its developers — presumed by some security experts to be “red hat’ hackers working with support from the Chinese government — open access to the messages, calls, contacts, location and even the bank information and passwords of those naive enough to download it.

That’s a harsh lesson not just for those living under authoritarian regimes, but for us citizens of nominally free and democratic societies as well.

The smartphone is by far the most formidable tool for populist empowerment ever invented, turning individual human beings into mobile broadcast platforms and decentralized mobs into self-organizing bodies. But it’s also jarringly easy for these devices to be used against us.

Here in the United States, revelations of the existence of massive government surveillance programs like the NSA’s PRISM have caused an uproar among digital libertarians. Likewise, criminal smartphone hacking and cloud cracking has led to the release of celebrity nude photos and sex videos, to the humiliation of those who thought them private.

The response from leading smartphone developers like Apple and Google has been to announce new methods of locking and encrypting information to make it harder for individuals, businesses or governments to gain access to our personal information.

But even as they add these fresh layers of security, they continue to extend the reach of these devices into our lives, with services that integrate frictionless financial transactions and home systems management into our smartphones, and wearable accessories that capture and transmit our very heartbeats.

Imagine how much control commercial exploiters, criminals — or overreaching law enforcement — might have if it gained access to all these features. The upshot is that we increasingly have to take matters into our own hands (and handsets), policing our online behavior and resisting the temptation to click on risky links.

It may be worth exploring innovative new tools that offer unblockable or truly secure alternatives to traditional communications, like the free VPN browser extension Hola, which evades global digital boundaries to Web access; open-source projects like Serval and Commotion, which are attempting to develop standards for mesh connectivity that route around the need for commercial mobile phone networks; and apps like RedPhone and Signal, which offer free, worldwide end-to-end encrypted voice conversations.

Most of these are works in progress. But as technology becomes ever more deeply embedded into our lifestyles, keeping our digital identities secure and private is becoming increasingly critical. And as the protests in Hong Kong have shown, the only solution may be to use technology to defend against technology — in other words, to fight fire with FireChat.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine