Story highlights

Bill Cosby's career not defined by "The Cosby Show"

Comedian was pioneering black actor, notable philanthropist

Exec: "Three most believable personalities are God, Walter Cronkite and Bill Cosby"

New book chronicles Cosby's influential life

NBC was wary of “The Cosby Show.”

Sure, Bill Cosby was a successful advertising pitchman and in-demand comedian. But for all his success, he hadn’t had a hit prime-time television show since “I Spy” in the ’60s.

Little did they know.

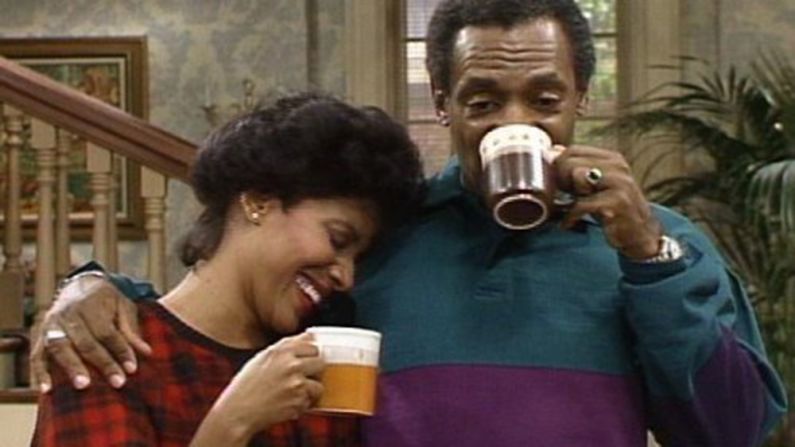

“The Cosby Show,” starring Cosby as doctor and family man Cliff Huxtable, premiered 30 years ago this week, on Thursday, September 20, 1984. It was expected to be a strong second to CBS’ hit “Magnum, P.I.”

Instead, it became a phenomenon: the No. 1 show in television five years running, the program that turned Bill Cosby into Bill Cosby.

Its effects weren’t limited to its star. Thursdays became TV’s biggest night, with “Cosby” leading a murderers’ row of NBC shows including “Cheers,” “Night Court” and “L.A. Law” – and eventually “Seinfeld,” “Frasier,” “Friends” and “ER.”

NBC, after spending the late ’70s and early ‘80s as television’s lowest-rated network, vaulted into the No. 1 spot and held it, on and off, for two decades. The sitcom genre, which had fallen on hard times, was recharged. You can draw a direct line from “The Cosby Show” to “Roseanne,” “Home Improvement” and “Everybody Loves Raymond.”

And some observers have even credited the show, with its upscale, photogenic black family, with smoothing the way for another African-American family to rise – all the way to the White House.

“Before Obama, There Was Bill Cosby,” headlined a story in The New York Times in describing the “Cosby Effect.”

But Bill Cosby was a trailblazer long before “The Cosby Show” came along. As “Cosby: His Life and Times,” a new biography by Mark Whitaker – a former Newsweek editor and CNN executive – points out, the man has been a cultural influence since the early 1960s.

“One of the things that I wanted to do in this book is remind people of all the different ways in which he was a pioneer,” Whitaker said in a phone interview. “Because ‘The Cosby Show’ was such an overwhelming success, there are people who forget that he was a pioneer in so many ways before ‘The Cosby Show.’ “

Indeed, the man contains multitudes: comedian, actor, philanthropist, activist. He is more than he seems, his rise and success paralleling decades in the life of America. Call it “The Seven Ages of Cosby.”

‘Cosby Show’: Our 10 favorite moments

1. The standup comedian

In some ways, much of Cosby’s persona was fully formed from the first moment he took the stage in New York’s Greenwich Village in the summer of 1962. The poor kid from North Philadelphia grew up listening to his grandfather tell Bible stories and his mother share the tales of Mark Twain. Cosby, also informed by a love of jazz, became a champion storyteller, focusing not on the rat-a-tat-tat of jokemeisters but on the deeply American rhythms of tale spinners.

“I don’t think it was an accident that the first routine he really became famous for was about the Bible – the ‘Noah’ routine,” says Whitaker.

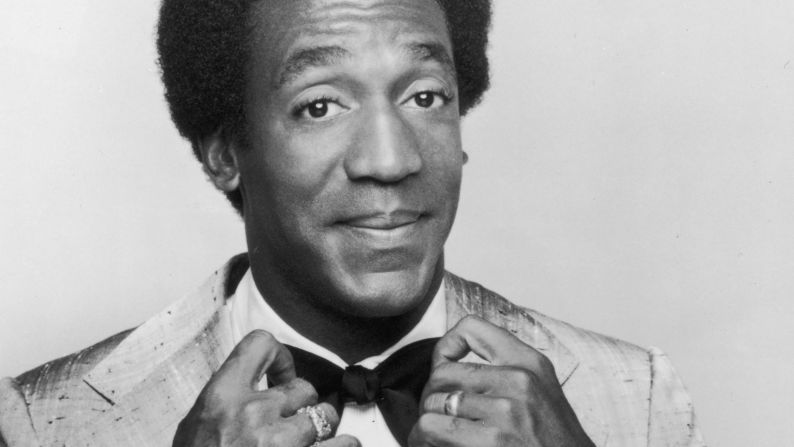

2. The multimedia superstar

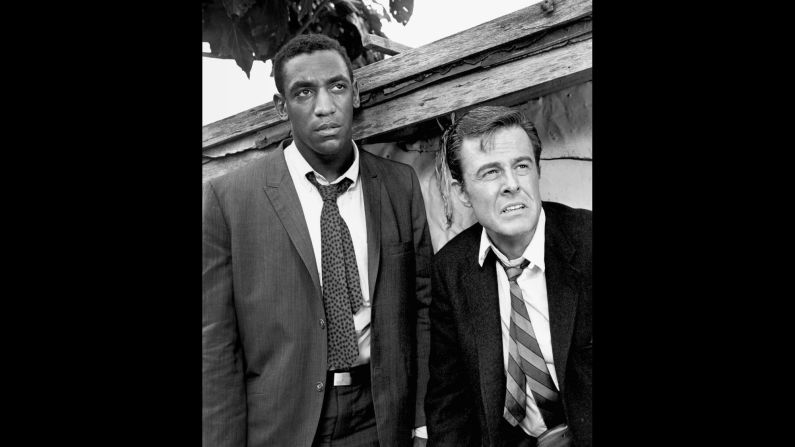

For all of Cosby’s early success as a comedian, he entered a whole new realm of stardom when he was selected as one of the stars of an NBC espionage drama, “I Spy.” He was the first black actor to star in a dramatic role on a network TV show, becoming “television’s Jackie Robinson,” in Variety’s words.

“I Spy” was no sure thing. Cosby had help from producer Sheldon Leonard, who stood up for his raw star when NBC got nervous, and co-star Robert Culp, who refused to make an issue of race.

In an era when there were few crossover stars, Cosby was a phenomenon. He won three Emmys for his performances in “I Spy.” His comedy albums, including “Wonderfulness” and “To Russell, My Brother, Whom I Slept With,” were best-sellers. He had plans for improving educational outreach (a personal passion) and he established a model for black stars to come.

3. Dr. William H. Cosby, Inc.

Cosby had many achievements after “I Spy” ended its run. On the personal side, he went back to school and earned a doctorate in education from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. (The subject of his dissertation: the role of another Cosby TV series, “Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids,” as a teaching aid.)

He also became TV’s foremost advertising pitchman, making commercials for Jell-O pudding and Coca-Cola.

“The three most believable personalities are God, Walter Cronkite and Bill Cosby,” said a Coke executive.

4. Everybody’s dad

Cosby’s popularity as an advertiser helped lay the groundwork for his return to network television, but first he had to remake himself as a comedian.

His ’60s routines often revolved around childhood, but by the early ‘80s Cosby was a 40-something father of five. His new routines looked at family relationships from a parent’s point of view.

If this made him seem out of touch to comedians who preferred the brashness of Richard Pryor – Eddie Murphy did a wicked Cosby parody on “Saturday Night Live” – a concert film, “Bill Cosby: Himself,” showed he still had the touch. Though it failed in theaters, endless runs on HBO earned Cosby a whole new group of admirers.

“As good as ‘Richard Pryor: Live in Concert’ is, the Cosby thing, as a piece of standup, I think, is even better,” comedian and producer Larry Wilmore told GQ in 2013. “I don’t think there was a better one before it, and I don’t think there’s been a better one since.”

5. Cosbymania!

And then came “The Cosby Show.”

Aside from the boost it gave both Cosby and NBC, the sitcom was notable in other ways. It took advantage of its hit status to showcase a number of notable black entertainers, including Sammy Davis Jr., Lena Horne and Stevie Wonder. In fact, the Wonder episode, which featured the keyboardist using a synthesizer to record and manipulate audio, later inspired hip-hop artists to make sampling a part of their mix.

The Huxtable home in Brooklyn Heights also featured paintings by black artists – an extension of a love of art by Cosby and his wife, Camille – and even made colorful sweaters a thing. (Yes, Cosby was well aware that not all the sweaters were attractive.)

30 years later, the Cosby sweater still rules

The show was sometimes criticized for presenting a sanitized view of the black family – one that seemed oblivious to the issues of being black in America – but Whitaker says that, too, was deliberate.

“Cosby was very aware of the power of television,” says Whitaker. “(When) coming into your living room to 35 and 40 million people a week, presenting a positive image – not only to white viewers but to black viewers – was deeply powerful and healthy.”

6. Touched by tragedy

“The Cosby Show” went off the air in 1992.

Cosby’s devotion to education paid particular dividends in the post-“Cosby” age. A “Cosby” spinoff, “A Different World,” “created an explosion in applications, enrollment and graduation rates at black colleges,” wrote HBCUDigest.com’s Jarrett L. Carter. Cosby himself donated to many schools, most notably a $20 million bequest to Atlanta’s Spelman College.

But the ’90s also gave Cosby some of his most difficult challenges. A woman named Autumn Jackson claimed that she was his daughter and demanded $40 million. He admitted an affair with Jackson’s mother, but denied paternity and Jackson later served time for extortion.

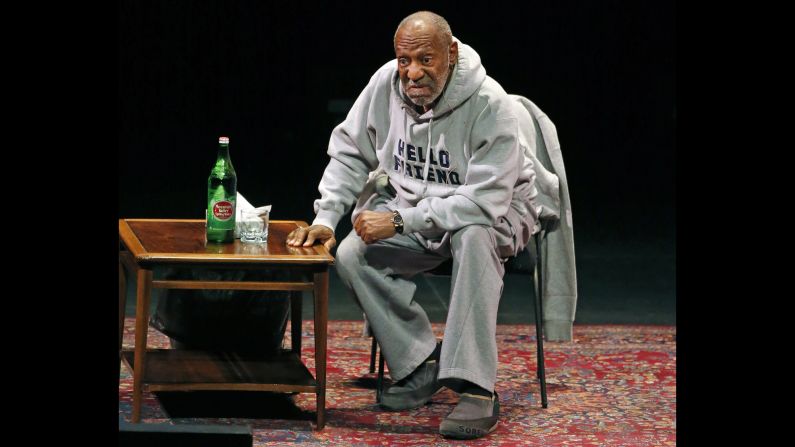

Cosby also suffered the loss of his son, Ennis, who was killed in an attempted robbery. The actor coped with the loss of his son by establishing a scholarship in Ennis’ name and routinely wearing a sweatshirt with “Hello Friend” – Ennis’ greeting – at concerts.

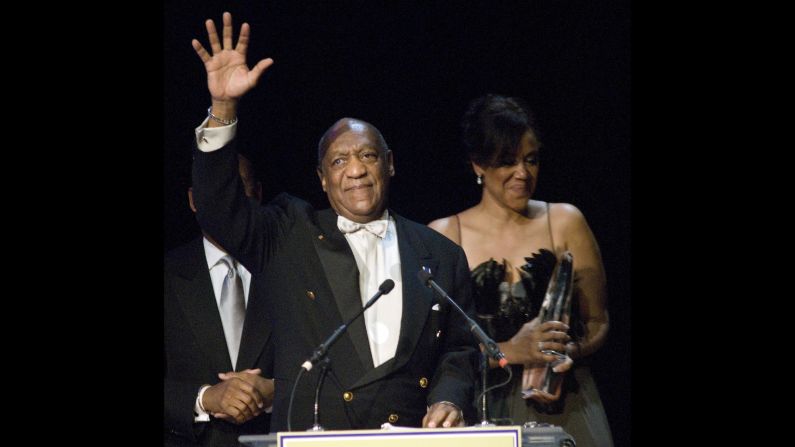

7. The wise elder

In the 21st century, Cosby has attracted more attention for his statements about the need for African-Americans to take responsibility for their lives. For that, he was depicted as a curmudgeon and a conservative, taking heat from such black writers as Michael Eric Dyson and Ta-Nehisi Coates, though Coates, in particular, later changed his view.

But Whitaker says that Cosby is simply stressing a philosophy he’s had all along, one that emphasizes education, social organizations and personal responsibility. The writer believes that in the time that he has left, Cosby is trying to be a positive role model, donating money to schools, meeting with children, and showing up at churches.

“You may disagree with his message, but he puts his money and his time where his mouth is,” Whitaker says.

And Cosby hasn’t slowed. At 77, he maintains a steady concert schedule and he has a new TV series in the works.

But 30 years after “The Cosby Show” premiered, Cosby’s legacy, says the author, will be his ability to bring people together.

“He was the entertainer who helped black people and white people – but beyond that, all people – see that they had more in common than they had differences,” says Whitaker. “He got them all to laugh together, and it’s really hard to be angry at people when you’re in the same room all laughing at the same thing.”