Vital Signs is a monthly program bringing viewers health stories from around the world.

Story highlights

The chemical "psilocybin"' found in magic mushrooms could be used to treat depression

Psilocybin causes the introspective region of our brain to become less active

Experiencing a "mystical mental state" could free people from addictions

Think of psychedelics and you’ll likely think of bright colors, hallucinations, spirituality, and an overall “mystical” experience. For centuries these drugs have been used in social, religious and medicinal contexts by cultures across the globe. But today, the ability of these drugs to alter our brain function is being tapped into as a potential therapeutic for a range of mental health conditions from anxiety and depression to addiction and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

“Only by losing the self, can you find the self,” explains Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, from Imperial College London. These may not be the usual words of a scientist but there is biology behind them. “People try and run away from things and to forget, but with psychedelic drugs they’re forced to confront and really look at themselves,” he says.

The drugs Carhart-Harris is referring to are hallucinogens such as magic mushrooms – specifically the active chemical inside them, psilocybin. “We’re beginning to identify the biological basis of the reported mind expansion associated with psychedelic drugs,” he says. Psilocybin is not addictive and is interesting to researchers for its ability to make users see the world differently. The team at Imperial College has begun to unravel why.

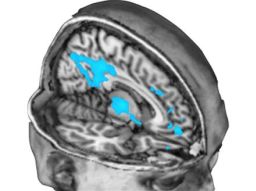

Carhart-Harris scanned the brains of 30 healthy volunteers after they had been injected with psilocybin and found the more primitive regions of the brain associated with emotional thinking became more active and the brain’s “default mode network,” associated with high-level thinking, self-consciousness and introspection, was disjointed and less active.

“We know that a number of mental illnesses, such as OCD and depression, are associated with excessive connectivity of the brain, and the default mode network becomes over-connected,” says David Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology, who leads the Imperial College team. Nutt was formerly drug adviser to the UK government but was fired in 2009. He “cannot be both a government adviser and a campaigner against government policy,” wrote a member of the British Parliament, at the time.

Read: The people with someone else’s face

The over-connectivity Nutt describes causes depressed people to become locked into rumination and concentrate excessively on negative thoughts about themselves. “By disrupting that network [with psilocybin] you can liberate them from those depressive symptoms by showing them it’s possible to escape those thoughts,” he says.

Depression is estimated to affect more than 350 million people around the world, according to the World Health Organization. The current pharmaceutical approach to treatment is with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as Prozac, which increase levels of serotonin in the brain to improve moods. But SSRIs are not effective in everyone, take time to show an effect and are generally prescribed for long periods of time to maintain their effect.

Nutt thinks psilocybin could be a game-changer, used as part of a therapeutic package where the mind-altering and confronting nature of psychedelics are combined with therapy to treat people within just one or two doses of treatment. “We’ve never had drugs before with an instant effect. This could create a paradigm shift to help people into a different state of thinking that they can then stay in,” he says.

But he stresses that psilocybin should be administered with professional support as part of medical therapy.

Psilocybin is illegal in many countries and in the United States it is considered a Schedule 1 drug. Schedule 1 drugs “have a high potential for abuse and serve no legitimate medical purpose in the United States,” according to the Department of Justice.

The U.S. National Institute of Drug Abuse says that long-term negative effects such as flashbacks, a risk of psychiatric illness and impaired memory have been described in case reports. Some people have frightening experiences while on psilocybin and can experience panic reactions, which may cause them harm to themselves or others.

Read: These 8 whiz kids are the future of medicine

This new research, however, has only scratched the surface of the brain and its consciousness. “The brain is about organizing information and predicting the external world and we think psilocybin disrupts that and makes it more chaotic,” says Nutt. “People have hallucinations because instead of seeing the world as the brain expects it to be, you see what the brain is doing.”

This “chaos” could potentially treat not only depression, but also addictions, such as smoking and alcoholism, which were the subject of some of the earliest studies on psychedelics in the 1950s and ’60s, before laws against the drugs were introduced.

“With psilocybin people feel reorganized [after therapy] and the nature of the reorganization is such that there are effects on attitudes towards addiction,” explains professor Roland Griffiths from the Johns Hopkins School of medicine.

The Centers for Disease Control estimates there are 42 million smokers in the United States and the habit accounts for one in five deaths each year. Initial studies by Griffiths and his team to treat smoking addiction have found 80% success rates in people quitting the habit up to six months after their treatment. Their studies indicate that psilocybin-based therapy could potentially be quicker and more effective than long-term therapies such as nicotine replacement.

The mechanisms behind the change aren’t fully understood but the therapy is thought to increase motivation and self-efficacy so people have more confidence in their ability to quit. “The default-mode network is about habitual patterns of behavior and decreasing activity in this system may free someone to think differently,” postulates Griffiths. “People say their addiction doesn’t seem compelling anymore.”

Similar small-scale studies on alcoholism by Michael Bogenschutz at the University of New Mexico have had equally promising results, with the greatest improvements seen in people after they had received psilocybin than after counseling alone. “The degree of improvement was highly correlated with the intensity of the subjective effects of psilocybin,” says Bogenshutz.

Psilocybin therapy is still a long way from widespread acceptance and trials need to be conducted on larger scales in controlled settings. “The early research is promising but further research is needed,” comments Dr Owen Bowden-Jones, of the UK’s Royal College of Psychiatrists.

“It will require much more research to establish whether these drugs work in clinical settings and are safe to use with patients,” he says.

But the trans-Atlantic teams envision a future of approved clinics administering these mind-alerting psychedelics in a supportive setting to treat various mental ailments. “It’s unlikely to become the mainstream treatment,” concludes Nutt. “But it could be used on people [with depression] when SSRIs aren’t working.”

Read: The people with someone else’s face