Story highlights

A man eventually headed for the U.S. died of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Nigeria

Had he arrived, he could have infected others

But an epidemic outbreak in the United States would be unlikely

In West Africa, the largest outbreak in recorded history has killed more than 700 people

A man boards a plane in Liberia with a slight fever. As the jet nears an airport in New York, his temperature rises; his throat grows sore.

It’s the flu, he thinks after he lands, but he’s wrong. He’s caught the deadly Ebola virus.

He soon dies of hemorrhagic fever while surrounded by family. Some of them catch it, and it’s like a flame hitting a fuse.

The United States erupts in its first Ebola pandemic as health care workers fight an uphill battle to contain it.

Could what sounds like the plot of a Hollywood pestilence thriller really happen here?

Well, yes and no.

Yes, Ebola can come to the United States.

But no, there’s no reason to panic.

“This is not an epidemic; it’s not the kind of disease that can sweep through New York,” said Dr. Alexander van Tulleken of Fordham University.

What is the risk of catching Ebola on a plane?

The ‘yes’ part:

Given that international air travel is commonplace, it’s realistic that an infected passenger could land in the country.

One nearly did.

Patrick Sawyer, a U.S. citizen working in Liberia, fell violently ill while on a plane to Nigeria this month. He was planning on returning to his family in Minnesota but died before he could.

“It’s going to happen at some point,” CNN Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta said.

A person can be infected and not show symptoms for up to three weeks. So it’s possible for someone to fly to the United States who has the virus but is feeling fine.

“Just observing the whole process, it’s almost impossible to prevent from happening,” Gupta said.

Then, the person could develop symptoms of Ebola hemorrhagic fever, which would make the patient capable of passing the virus.

To catch it, one has to come into contact with a sick person’s bodily fluids: sweat, saliva, blood or excrement.

The ‘no’ part:

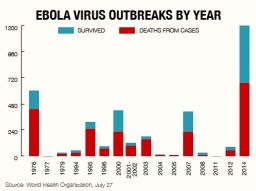

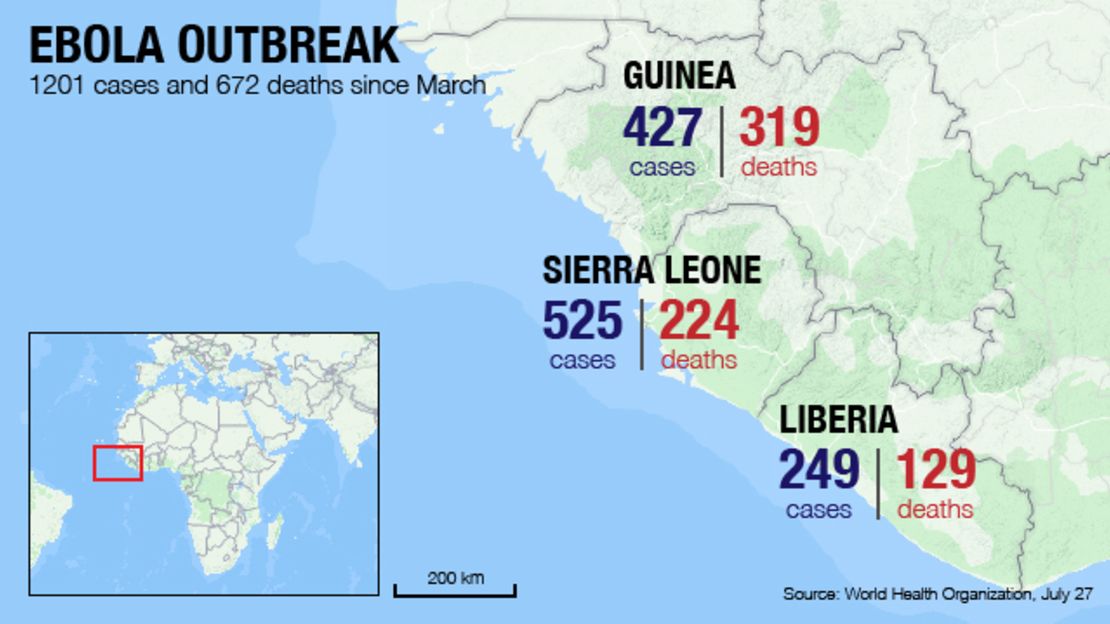

Experts agree that the disease would not spread far like it has in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, where health officials believe it has killed more than 700 people in the largest Ebola outbreak in recorded history.

There are two reasons for this:

• Though Ebola is aggressively infectious, which means that those infected are highly likely to get sick, it’s not very contagious, meaning that it doesn’t spread easily.

• Public health educators and medical professionals in the United States and other highly industrialized countries would deal with it swiftly. It’s an advantage the poor affected countries in West Africa don’t have.

“It certainly is feasible that someone could come to the United States who is infected and gets sick here. No one’s denying that,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health. But the health care system in the United States gives it the ability “to do the kind of isolation that apparently is very difficult to do within the health care infrastructure in the African countries that we are talking about.”

The ‘why not’ part:

To answer that, consider the following:

1. Knowledge is key

That’s one of the big advantages that industrialized nations, such as the United States, have in fighting Ebola’s spread.

First, teach health care workers to recognize Ebola cases. Then quarantine them. Then keep people out of contact with their bodily fluids while it runs its course.

The CDC has alerted health workers in the United States to keep an eye out for symptomatic patients who have recently traveled to West Africa.

If a case does turn up, public health officials will work to rapidly track down other people the patient has come into contact with and screen them for the virus.

They are currently looking for anyone who may have come into contact with Sawyer.

2. There’s little superstition surrounding Ebola here

“Epidemics of disease are often followed by epidemics of fear and epidemics of stigma,” said Dr. Marty Cetron of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “All these kinds of things occur in a social context that can make containment very, very challenging.”

In many parts of West Africa, rumors have spread that eating raw onions will protect from the disease while mangoes may promote it, the World Health Organization has said.

Villagers carry out their usual burial of the dead, coming into contact with bodily fluids and infecting themselves.

With too few people to mount a tough battle against the spread of the disease itself, aid workers have said they are putting a lot of emphasis on education.

They are teaching local residents to stay out of contact with the virus while they treat the sick. But locals often view them with suspicion, some accusing them of bringing the disease to the country.

3. There’s ready access to basic care

“We don’t have a vaccine, and we don’t have any drugs that work on it at the moment,” van Tulleken said. “The treatment is entirely what we call supportive care.”

Much of the treatment involves simple nursing, things such as proper hydration and nutrition.

In places where aid workers in West Africa have done so, they have been able to save about 45% of those infected.

Without treatment, the death rate can run as high as 90%, Medecins sans Frontieres has said.

A pretty good way not to catch the virus is not to come into unprotected contact with sick patients.

That’s why Ebola caregivers dress in head-to-toe protective gear with masks and patients are isolated in tent-like structures, making it look like the scene of a chemical spill.

How the United States and the West can help is to devote money and staff to contain the virus in West Africa.

“We’re not doing a brilliant job of containing the epidemic in terms of the resources we’ve devoted to it so far,” van Tulleken said.

Ebola outbreak cripples West Africa, threatens beyond

Deadliest-ever outbreak: What you need to know

Ebola doctor in Sierra Leone dies

CNN’s Jacque Wilson contributed to this report.