Every week, Inside Africa takes its viewers on a journey across Africa, exploring the true diversity and depth of different cultures, countries and regions.

Story highlights

Two billion people eat insects in 162 countries around the world

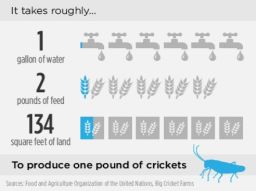

Insects need less food, water and land to rear than beef and chicken

Social enterprise Aspire is trying to increase insect consumption globally

It thinks its Ghana pilot program will revitalize the economy

Palm weevils. To look at, these tiny bugs are relatively unassuming, perhaps even slightly creepy to the insect-adverse. To Mohammed Ashour, however, they are the solution to many of the ills facing the developing world. The humble palm weevil could potentially eradicate world hunger and malnutrition, it could lift whole communities out of poverty, and bring down global C02 levels. For a creature measuring just a few inches in length, that’s a lot of power.

“If anything, our business model is too disruptive,” says Ashour, who launched Aspire with four fellow MBA students from McGill University. Their aim is to introduce insect farming to countries with an affinity for insect consumption and a lack of access to nutritional sustenance.

Their idea won them the 2013 Hult Prize, which provides $1m seed money for the most game-changing social enterprise, as well backing from the Canadian government-funded Grand Challenges. With their winnings, Aspire set up a pilot program in Ghana, where food insecurity remains an issue in various parts of the country.

Currently, 75% of pre-school-aged children and two-thirds of pregnant women in Ghana suffer from anemia, according to the World Health Organization.

“In the rural community, the food is mainly made up of carbohydrates. Because of the fact that you’re not getting the protein you need – there isn’t much fish or beef in the diet – I think what they eat is lacking in nutrition,” says Dr. Clement Akotsen-Mensah, an entomologist and research fellow at the Forest and Horticultural Crops Research Center at the University of Ghana.

“The palm weevil can be a good supplement,” he adds.

In 2013, the UN Food and Agricultural Organization released a report advocating insect consumption worldwide. The report found that pound-for-pound, palm weevils – like other insects – have similar levels of protein as beef, but beats out the bovine in levels of iron, potassium, zinc, phosphorous and several amino acids.

While the government supplies pregnant women with iron pills and vitamins, Ashour says locals aren’t always too amenable to taking them.

“In areas where iron deficiencies seems to be the greatest, there is also a lack of education, or sometimes a lack of trust in government. If you go to a small village outside of Accra, good luck instructing a woman to take a package of pills and expect an order of compliance,” he notes.

“We’re introducing iron and protein in a way that is much more culturally acceptable.”

Read: What causes Namibia’s fairy circles?

Moreover, some Ghanians, particularly those living in the north and east, already make palm weevils a part of their diet.

“You won’t see it everywhere in Ghana, but in places where it is consumed, it is consumed with quite a high affinity,” says Ashour.

While he notes that Ghana has “a strong demand,” he says what it lacks is supply, as currently the bugs are harvested by hand. By introducing farming, Aspire is not only increasing access to a cheaper and more nutritional source of protein, it says it is introducing new revenue streams for Ghanians living in poverty.

“The process of farming itself isn’t overly complicated. Someone who is uneducated but industrious can do it and get it up and running in a short amount of time,” says Ashour.

Aspire has decided to target farmers living in rural and peri-urban communities, where, Ashour notes, there is an abundance of land, but a dearth of opportunities. Aspire would provide farmers with the kits and training free of charge, then buy back the weevils to distribute en masse throughout the country. Aspire is also looking into creating products from the weevils, such as a high-protein flour that could be added to any dish to make it more nutritious.

“I think it has a lot of potential,” says Akotsen-Mensah.

“Previously, the wood from the palm trees wasn’t really used for anything. People would make wine from it maybe, then leave it. Now they can use it to raise the weevil, and get some small income. It could have a great economic impact,” he adds.

Aspire has other insect-farming projects it’s either launched or is looking into. The group has also set up a pilot grasshopper-farming program in Mexico, and is looking into introducing cricket farming in Kenya. The choice of insect is determined by local tastes. It is also looking at introducing entomophagy – or the practice of bug-eating – into the United States.

While the project in Ghana is fairly new (Aspire launched the program less than three months ago), Ashour has high hopes for it, ultimately envisioning his weevil products to reach 30% of the market in Ghana.

“You’re asking an optimist,” he concedes. “I really see us having great impact. By next year’s end, it would be possible to reach anywhere from 500,000 to one million people.”