Every week, Inside Africa takes its viewers on a journey across Africa, exploring the true diversity and depth of different cultures, countries and regions. Follow host Errol Barnett on Twitter and Facebook.

Story highlights

Timket is an Ethiopian holy festival that re-enacts the baptism of Jesus

Historical bath is filled with holy water for the festival, pilgrims jump in

Thousands of visitors flock to Gondar for the event

Priests parade replicas of the Ark of the Covenant

France has Lourdes, India has the Ganges. Ethiopia, meanwhile, has Gondar.

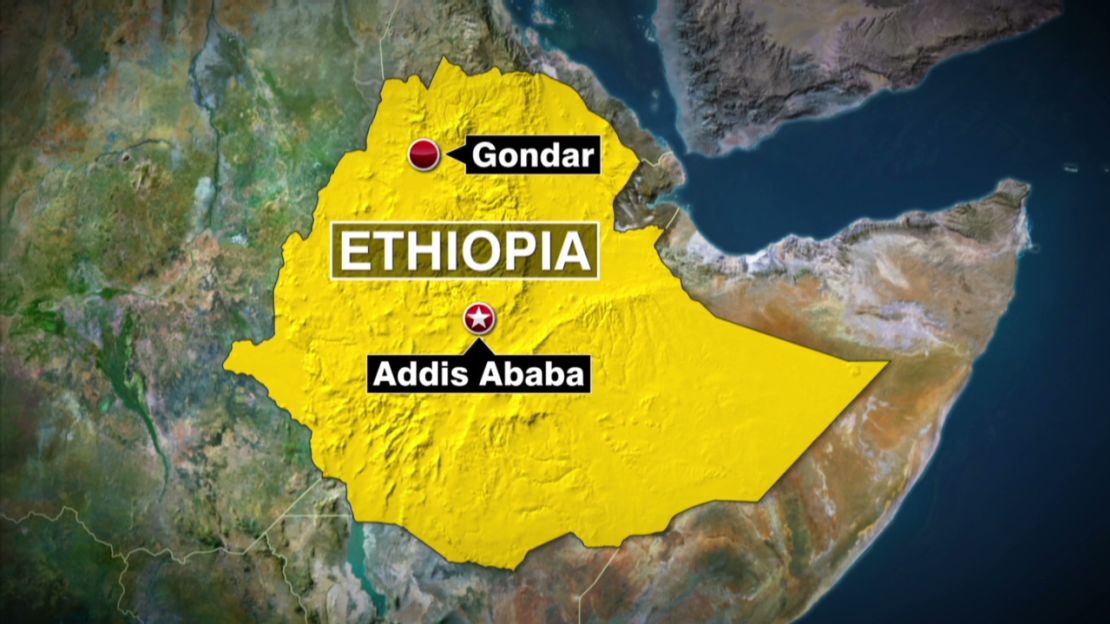

Situated about 450 miles north of Addis Ababa, encapsulated by hills and tall trees, and dotted with 17th-century relics from the city’s glory days (when it was the country’s capital), Gondar today can seem somewhat remote. During the religious festival of “Timket,” however, the city is inundated with pilgrims who come to re-enact the baptism of Jesus in the River Jordan, and take a dip in the holy waters at the historical Fasilides Bath.

Nearly two thirds of Ethiopia’s 94 million population is Christian, and the majority of those belong to the Orthodox church. For them, Timket – celebrating the Epiphany – is among the most important occasions of the year. It’s is a two-day affair that begins with a procession of “tabots,” holy replicas of the Ark of the Covenant – the sacred chests described in the Book of Exodus as carrying the stone tablets on which the 10 Commandments were written.

The tabots are wrapped in cloth and placed on the heads of Ethiopian Orthodox Christian priests, who parade the streets en route to the bath. The priests, clad in ceremonial robes, are escorted by drums and by the clapping and singing of worshipers, who hold an overnight vigil until dawn.

There are services the following morning which culminate in the priests blessing the waters of the historic bath, while onlookers crowd every nook surrounding the bath – some getting a pristine view from nearby trees.

When the priests are done, the mood turns jubilant, and the spectators rush to jump into the pool.

“The water is blessed in the name of the Holy Trinity … in the name of God. The water is now sacred, and the sick shall be cured,” explains Ezra Adis, the head priest at the local Medhanelem Church.

“That is why the young people who jump in first get excited; it is a spiritual love,” he adds.

Read this: Ethiopia’s churches “built by angels”

The plunge is so swift that some participants get battered in the process – though most are unperturbed by a few scratches.

“I jumped from high above,” boasts one man who dived into the waters from one of the nearby trees.

“I was apprehensive,” he adds. “The branches could give way and you could fall on the rock edge of the pool, and there was a possibility I could have lost my life, but at this moment, I am doing what I feel good about, and that possibility of death doesn’t scare me.”

The Timket festival dates back to the 16th century, but it was marked only in churches until the baptismal ceremonies were introduced, explains Bantalem Tadesse Tedla, a historian at the University of Gondar.

The baptisms, usually held on January 19, are celebrated differently in other parts of the country. “There are three options for Timket,” says Tedla. “To be immersed, to collect water from three pipes and pour it on people, or to collect water and sprinkle it – it depends on the availability of water.

“In Gondar, the first is implemented, because of the existence of this very important building,” he adds, referring to the stone bath – a UNESCO world heritage site built in 1632 for King Fasil (Fasiledes).

As the afternoon winds down, people begin to leave the pool and head back to the streets, but the festivities aren’t quite over. Each tabot is now paraded back to its respective church with crowds of onlookers eager to get one last look at them.

Back at the churches, it’s a different, quieter scene. Congregants fill the church grounds to listen in on a final service, and after a closing prayer it’s time to send the tabot back inside the church to its resting place.

The locals will eventually return to their homes for a special feast, but in the meantime, the celebrations on the streets of Gondar continue – a chance for orthodox Christians to celebrate and come together for one of the most sacred and festive days of the year.