Story highlights

Google Glass users have faced some negative reactions from businesses and strangers

Most people are curious, but many have privacy concerns about the wearable devices

Though they both have cameras, the reaction to Glass is different than smartphones

Carolyn Capern and her business partner Greg Trujillo were eating breakfast in a Panera bakery in Florida recently, each wearing Google Glasses but actually immersed in their smartphones when they were accosted by an angry stranger.

Though they’d only had the beta devices for about a month, they’d become accustomed to curious people approaching them like they were minor celebrities, peppering them with questions about the still-rare technology, asking to try it on and even getting their pictures taken wearing it.

But the man in the bakery didn’t want a demonstration. He was interested in confrontation. He asked if they would be comfortable with him recording a video of the pair on his phone, violating their privacy and rights in the same way he felt they were violating his by wearing recording devices on their faces in public.

“He said we were being very intrusive and invading his sense of privacy and was altogether quite upset that we were there wearing Google Glass,” Capern said.

A different kind of backlash

Negative reactions to Google Glass have been making headlines lately. Earlier this year, Seattle entrepreneur Dave Meinert preemptively banned people from wearing Glass at his 5 Point Café before the technology was even released. Recently he made headlines again after a manager at another one of his restaurants, Lost Lake Cafe & Lounge, asked customer Nick Starr to leave for refusing to remove his Google Glass while inside.

The burgeoning dissent is sometimes not pretty. Early adopters have been handed a less-than-flattering nickname in some circles: “Glassholes.”

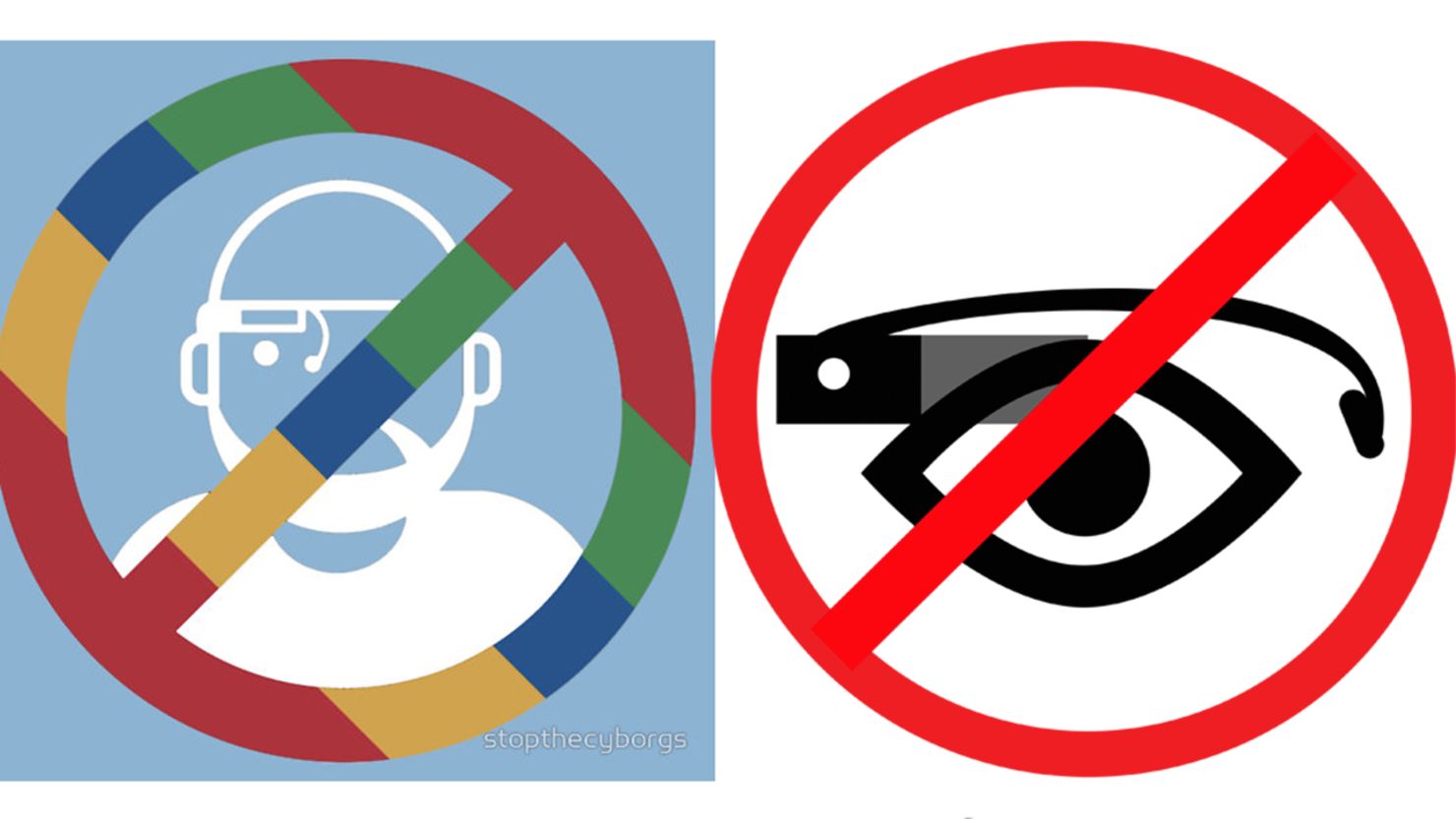

A group calling itself Stop The Cyborgs offers free anti-glass icons and art on its site for businesses that want to notify customers the technology is not allowed. State and federal lawmakers have expressed privacy concerns about the technology and are, if you will, keeping an eye on it.

Even though Glass wearers claim these types of responses from businesses and individuals are not the norm, there is something different about the negative early reactions to Google Glass than what has greeted the smartphone and other new technologies in the past.

While there may be some old fashioned technophobia at play, many of the criticisms come from members of a tech-savvy generation that embraces smartphones and tablets. Lost Lake Cafe even encourages patrons to post photos taken at the business to Instagram and tag them #LostLake, according to The Stranger.

So what is it about Google Glass that elicits such different reactions?

“People make a personal decision to check their smartphone or log in and check their social media accounts, but Google Glass is out of their control,” said Larry Rosen, a psychologist who focuses on technology. “They are not able to make a decision as to whether they want to be ‘on’ or ‘connected’ through someone else’s process, and they are concerned and unhappy that they do not have a say in the matter.”

People feel in control when using their own technology but, fairly or not, Google Glass seems to them more like invasive surveillance.

“For the most part they have given up privacy gladly to be connected through all possible modalities. However, that is when the choice is their choice. This is not,” Rosen said. “This is someone else essentially eavesdropping on their lives, and if they want to give up their own privacy, they seem to want to do it on their terms and their timeline, not someone else’s.”

Easing fears with education

The technological differences between smartphones and Google Glass are minimal. Both have cameras that can record videos and audio and take photographs. Both can instantly upload recorded information to social media sites and other locations including Google services.

One of the primary concerns people have about Glass is that it is difficult to tell when the device is recording you. With a phone, a stranger would have to physically hold up the device and point the camera in the subject’s direction, a visible cue that they are recording. Wearable cameras like Glass are always pointed and ready to go.

Because there are still so few Google Glass units in the wild, many people don’t fully grasp the device’s limitations, according to Trujillo. Some have the misconception that Google Glass is constantly recording video, but leaving Glass in record mode would kill the battery in about an hour.

There is no external indicator light to show when Google Glass is in recording mode, but the screen is actually a transparent cube of glass, and people who are in close proximity can see a light when the system is on.

“It’s very easy to identify whether the screen is on or off if you know what to look for,” Capern said. (Both her and Trujillo’s devices were turned off during the bakery incident, they say.)

Like picking up a phone and pointing, there are physical indicators that might give away the fact that someone is recording. To take a photo or start recording a video with Glass, the wearer has to speak to or touch the device.

Trujillo and Capern think it’s actually easier to secretly record someone with a smartphone because they are far more ubiquitous and someone can just pretend they’re holding it up to read a Web page, check Facebook or send a text.

“The phone, in my opinion, is a lot more of an invasion-of-privacy device than Google Glass because you can actually tell when somebody tries to use Google Glass,” Capern said.

Navigating the future

Stop The Cyborgs is also concerned with the collection of big data through tools like Google Glass. Massive amounts of data can be automatically uploaded from wearable tech and phones to Google services, social media or other cloud-based storage. Google+ currently has facial recognition technology but has not yet tied it into Google Glass.

“The issue … is not the device itself but rather ownership and control over the data, and power relations and social norms around surveillance and control,” the organization says on its About page.

Legally, Glass users have the same rights as photographers when it comes to recording and photographing in public. You can photograph anything in plain view, including strangers, while in public places. Because video recordings include audio, the ACLU points out that state wiretapping laws might make some video recordings illegal.

When it comes to private property, the property owner has the right to prohibit photography in their home or business, typically by posting rules or asking people taking pictures to leave the premises.

Trujillo thinks the restaurants instituting bans are just looking for free press coverage, but there are many bans on Glass based on practical concerns.

A woman who was pulled over for speeding in San Diego was also ticketed for wearing Google Glass while driving, the device classified as a distraction much like a smartphone or other monitor. Illinois is considering explicitly banning Glass behind the wheel.

Many casinos have banned wearable computer screens which they fear could be used to cheat or count cards, and some theaters worried about piracy have added Google Glass to the list of recording devices prohibited for audience members.

Wearable technology like Google Glass is still in its early stages. The companies producing the gadgets hope they’ll be seen as normal and become accepted in the same way smartphones are. Until then, early adopters like Google Glass Explorers will have to handle the attention, both positive and negative.