Story highlights

Exclusive interview with world's most famous female architect Zaha Hadid

Designer behind new luxury Blohm+Voss superyachts: "Frames like veins"

Iraqi-born Briton says building Baghdad's central bank would be "very special"

Thinks conditions of construction workers is the responsibility of governments

When I first meet Zaha Hadid she’s as tight-lipped as a closed door. This is a woman who doesn’t do idle chit chat. Why would you when you’re the world’s most famous female architect?

Asked if people needed to be a little afraid of her, the brusque answer is “No,” before shooting me a case-closed expression. “I think people are always intimidated by something. I don’t do things that scare people off.”

“Full of lies,” is her response, when I refer to one article in which she demanded flight crew swap her plane, while taxiing on a runway.

Forty minutes later, Hadid has softened somewhat, opening the door on a remarkable life that began in 1950s Baghdad, before smashing through the “boy’s club” of international architecture, to become one of the most celebrated – and divisive – designers on the planet.

Perhaps the urban legends about her formidable demeanor are part of the mystique that has built up around the 63-year-old Iraqi-born Briton, who today boasts over 400 staff and 950 projects in 44 countries – including plans for Japan’s 2020 Olympic Stadium and the recently opened Serpentine Sackler gallery in London’s Hyde Park.

Dozens of models of Hadid’s distinctive white, sweeping, space-age designs sit on undulating plinths in her gallery in east London’s fashionable Clerkenwell.

The installation is called “City of Towers,” and sitting a little behind this mini metropolis is the creator herself, dressed in a black cloak at a long table of rippling glass.

“Frames like veins”

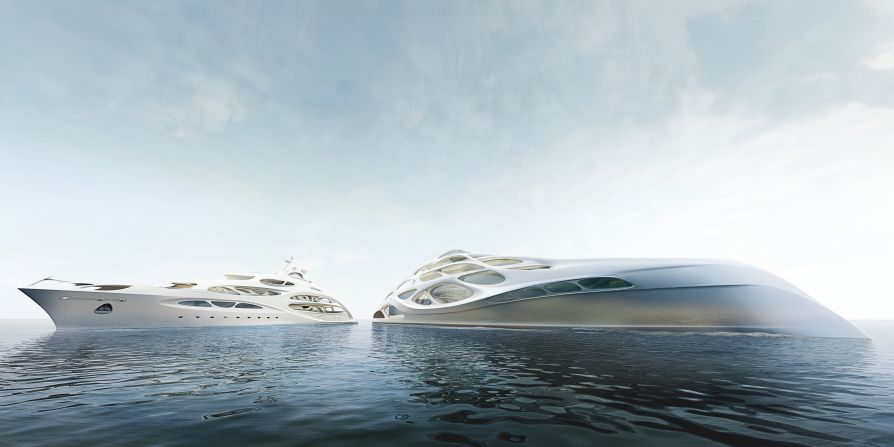

Her latest project is for German superyacht builders Blohm+Voss – the same company behind billionaire businessman Roman Abramovich’s “Eclipse,” the second-largest private yacht in the world.

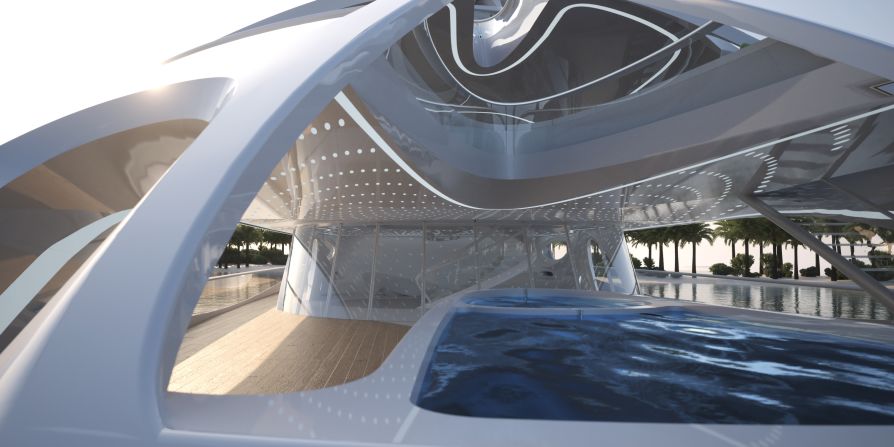

On the wall behind her, a plasma screen flashes computer-generated images of her six boats, their gleaming exoskeleton frames seamlessly weaving together each luxurious level. They range from a 128-meter “master prototype” to a 90-meter version called “Jazz.”

There’s barely a right angle in sight. So just what goes on in the mind of an architect who has created buildings with the most intriguing shapes?

“The idea was that the frames could be like veins,” explained Hadid. “I like this kind of project because every time you do them, you learn about some other type of parameters which you had not always considered.

“Unfortunately, architecture, as much as we’d like it to float, it doesn’t. That’s one thing that’s different – architecture is tied to gravity.”

Read: The $15m yacht controlled by an iPad.

“I never took ‘no’ for an answer”

Gaze across the sweeping roof of Hadid’s London Aquatic Centre or the overlapping limbs of Rome’s MAXXI museum, and you get the feeling these fluid forms are not harnessed by gravity at all.

For fans, they’re beguiling creations which redefined architecture for the modern age. For detractors, they’re overbearing and over budget.

Either way, there’s no denying Hadid’s phenomenal success, the first woman to win the Pritzker Prize in 2004 – regarded as architecture’s Nobel – and in the last decade going from the architect who never built anything to the architect who built everything.

“I never took no for an answer. I never sat back and said ‘walk all over me, it’s OK,’” she says about her headstrong approach.

“In London it was very timid, people behave well, they’re polite – especially if you’re a woman. A woman should behave properly. It means that you don’t challenge the situation.”

Indeed, when Vienna’s MAK museum had an exhibition of her work in 2003, attendants wore t-shirts emblazoned with Hadid quotes such as, “Would they still call me a diva if I was a man?”

Is there a defiant twinkle in her eye as she recalls the incident? “If you’re a man you’re seen as someone who’s tough and ambitious,” she says. “But when a woman is ambitious it’s seen as bad. I think things have changed in the last 20 years. They’re better. But there’s still prejudice.”

Read: World’s ‘most exclusive club’ admits women

From an outside perspective, Hadid’s determination has paid off, finally cracking the notoriously masculine world of architecture. She disagrees.

“I think it’s a boys’ club everywhere,” she says. “And I’m not privy to that world so much – they go fishing, they go golfing, they go out and have a drink. And as a woman you’re excluded from that bonding. It’s a big difference.”

“We were building a new world”

Hadid grew up in a Bauhaus-inspired home in Baghdad, her father leader of the Iraqi Progressive Democratic Party, a man who highly valued education.

She and her two brothers were sent to boarding school in England, before later gaining a degree in mathematics from the American University of Beirut.

As a teen she was inspired by a 1960s post-war boom in modernist architecture, when exciting new designs made the cover of Time magazine.

“There was a sense of optimism, we were building a new world that was demolished during the war,” she said. “There were new ideas, new materials.”

At 22 she moved to London to train at the radical Architectural Association, under the tutelage of influential Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, who famously called her “a planet in her own inimitable orbit.”

What did he mean by that?

“I often wonder that myself,” Hadid says with a chuckle, revealing a cheeky gap-toothed smile. “When he said it at the time, I was upset. But in a way he was right – I should not have a conventional career and he was absolutely spot on.”

The renegade planet that is Hadid kept hurtling forward, setting up her own London practice and, in 1993, completing her first building – the Vitra Fire Station in Germany. She recently returned for its 20th anniversary.

“When I go back 20 years later, buildings look very different – they’re either smaller or not as you expect them.”

Read: 162 years of America’s Cup yacht design

But it was the 1995 Cardiff Bay Opera House in Wales – a commission she won twice, but was thwarted by local politicians – which nearly ended her career, and helped shape the steely woman who last year was honored by Queen Elizabeth for her services to architecture.

“I know a lot of people thought I would give up, because it was such an awful, painful experience. I remember the day it happened I thought, ‘I will not let this finish me.’ In a way, it saved me. I think it did make me stronger,” she said.

“I wouldn’t build a prison”

Today, it’s difficult to imagine many developers turning down the celebrity architect, her buildings dotted everywhere from Beijing to Azerbaijan.

Is she concerned about the human rights credentials of the countries she works in?

“As an architect, if you can in any way alleviate an oppressive situation, or elevate a culture, then I think that you should. It’s different if someone asks you to build a prison – I wouldn’t do it. But if I’m doing a museum or a library, I think that’s different,” she said.

And the conditions of the construction workers?

“It’s not your responsibility really. I think different nations should take care of their workforce.

“As an architect, if you are involved in every layer then honestly you don’t do anything. I’m not saying I shouldn’t be thinking about it, but I think it’s a job for the politicians, for the media, for the locals, to deal with it.”

One country yet to host a Hadid original is her native Iraq, though she has been commissioned to build Baghdad’s new central bank – when that will actually happen is anyone’s guess.

But you get the feeling that no matter how hugely successful Hadid is, she will always paint herself as the feisty underdog – as much a part of her distinctive brand as undefinable space-age shapes.

“When you’re younger you just want to bang ahead. But it is very tiring, this constant fighting,” she said.

“Of course, we are more accepted now, but there’s always a reminder of the time when they resisted – the only fundamental difference is before they resisted because they thought we were crazy.

“Now they resist because they think we’re successful.”