Story highlights

Arthur Ashe won three grand slam titles

First African American to achieve feat of winning a slam

Died aged 49 in 1993 of AIDS related illness from an infected blood transfusion

Stadium court at Flushing Meadows named in his honor

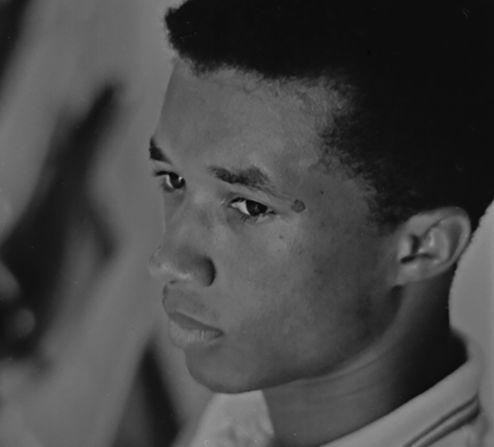

Tennis hero, inspiring role model for African Americans, social activist and high-profile campaigner for the HIV and AIDS communities, Arthur Ashe died in 1993, but it is a measure of his influence that, decades later, he shines as brightly as ever.

The main stadium court at Flushing Meadows, where the US Open is staged, is named in his honor, a striking statue of Ashe adorns the grounds, while the Arthur Ashe Kids’ Day is a glittering annual bash that kick starts the fortnight for the final grand slam of the season.

Michelle Obama was the guest of honor in 2013, while Bradley Cooper, Carmelo Anthony, Justin Bieber and Will Ferrell have been included in an eclectic list of celebrities over the years.

Ashe’s widow, Jeanne Moutoussamy Ashe, has made it her life’s work to ensure that her late husband’s memory is preserved for generations and the presidential endorsement is the icing on the cake.

“It makes me very proud that Arthur has his name raised up for kids who didn’t have a clue who he is,” she told CNN’s Open Court program in 2013.

“It was such a great honor. I’m born and raised on the south side of Chicago, as is Mrs. Obama, so to be sitting here next to her with her daughters was just great fun.

“And that she’s so supportive of the Arthur Ashe Learning Center and so supportive of Arthur’s legacy. I don’t think we could have asked for a better situation that day, it was just wonderful.”

Moutoussamy Ashe was sharing her experiences with former American Davis Cup star James Blake, who retired from the ATP Tour in 2013.

Blake told her that Ashe has been his idol and inspiration growing up.

“Being an African American playing tennis, his impact on me was great and I wanted to follow in his footsteps, being someone that went to college and was educated and had such a great influence on the world,” he said.

The impact that Blake talks about went far beyond the narrow confines of professional sport.

Ashe once famously said: “I don’t want to be remembered for my tennis accomplishments” and Moutoussamy Ashe has done her level best to promote his wish.

“The game of tennis really just gave him a platform to speak about the issues that he cared so much about,” she said.

“I think he was a role model for a whole lot of kids which is why his legacy is so important to promote today.

“We don’t want a whole generation of kids today and generations to come to not know that he was more than a tennis player.”

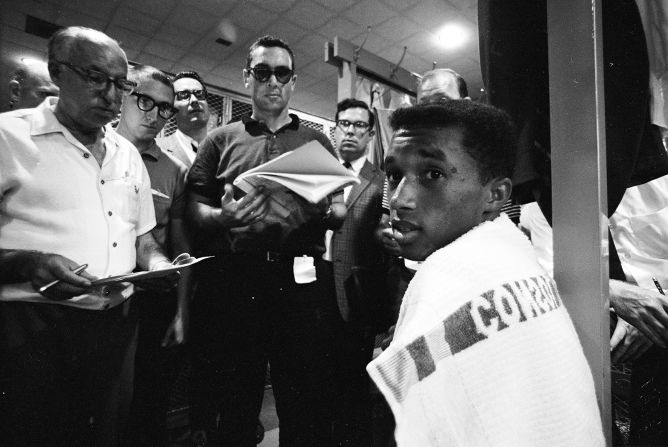

Born in 1943, Ashe was brought up in the segregated South in Richmond, Virginia and first tested his tennis skills on a Blacks-only playground in the city.

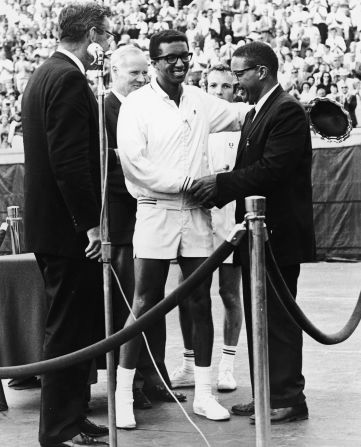

He developed his talent in high school and earned a tennis scholarship to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in 1963, that year becoming the first African American to represent the United States in the Davis Cup.

A member of the Reserve Officers Training Corp (ROTC), Ashe was eventually required to do military service and spent three years in the United States Military Academy at West Point, rising to the rank of second lieutenant.

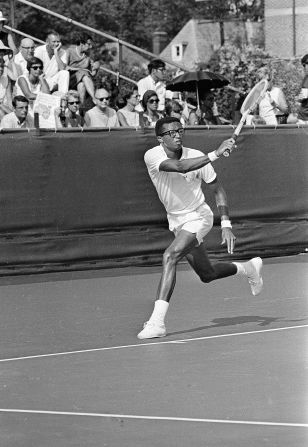

Ashe was still a serving officer when he won his first grand slam title at the 1968 US Open, the first of the Open Era when professionals were also allowed to compete.

“He wasn’t just the first African American male to win the US Open, but he actually was the first American period to win the US Open because the US Open didn’t begin until 1968,” Moutoussamy Ashe emphasizes.

Ashe was discharged from the Army in 1969 and, after winning his second grand slam crown at the 1970 Australian Open, turned professional.

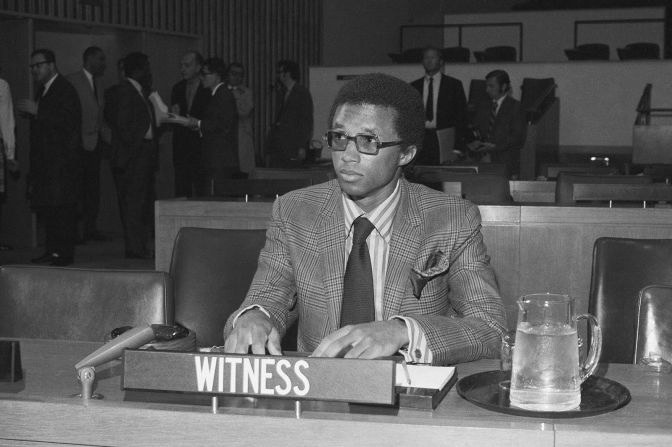

A prominent supporter of the American civil rights movement, Ashe’s political principles were tested when he was denied a visa by the apartheid government of South Africa to compete in their national open later that year.

Ashe campaigned for South Africa to be excluded from the International Tennis Federation but although his demands were not met, he was eventually allowed a visa to compete in the 1973 South African Open, the first Black male to do so.

Ashe continued to speak out against the apartheid regime and after Nelson Mandela was released having served 27 years in prison, the tennis star returned to South Africa in 1991 as a member of a 31-strong delegation to observe the profound political changes in the country.

He met Mandela several times and modestly observed: “Compared to Mandela’s sacrifice, my own life has been one almost of self-indulgence. When I think of him, my own political efforts seem puny.”

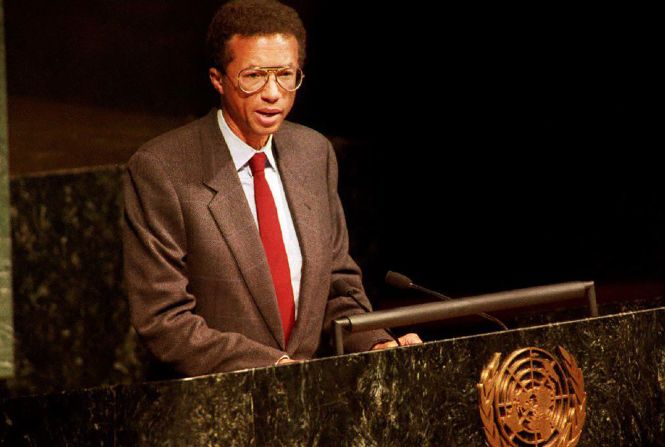

But others would disagree. Andrew Young, the former United States Ambassador to the United Nations, once famously said of Ashe: “He took the burden of race and wore it as a cloak of dignity.”

Young, a pastor turned leading politician, presided over Ashe’s wedding to Jeanne in 1977 after they had met at a charity event just six months previously where Moutoussamy Ashe was attending as a working photographer.

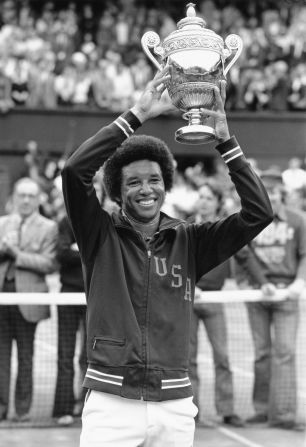

Ashe was by then a three-time grand slam singles champion having shocked top seed Jimmy Connors in an epic 1975 Wimbledon final, but it was to prove his last as injury and eventual illness took their toll.

The world was shocked in 1979 when the super-fit Ashe suffered a heart attack and underwent a bypass operation.

He was set to return to the tennis tour when further complications arose and he was forced to announce his retirement, doing it in typically fastidious fashion.

“He had about 30 letters that he had written individually to people, contracts that he had, promises and commitments he had to people, he just wrote them personally and said: ‘I’m retiring and I want you to be the first to know,’” recalled Moutoussamy Ashe.

In retirement, he took over as captain of the United States Davis Cup team, but in 1983, he had to undergo a second round of heart surgery in New York.

It was during this operation that Ashe is believed to have contracted the HIV virus from infected blood transfusions.

He learned of the diagnosis in 1988 after another health scare, but for the sake of their adopted two-year old daughter Camera, Ashe and his wife kept the illness private.

Only in 1992 was he forced to go public and, true to his ideals, began campaigning to debunk myths about AIDS and the way it is contracted.

He founded the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of Aids to build on the work of an institute he had set up to promote public health.

Ashe completed his memoir, “Days of Grace,” shortly before his death on February 6, 1993 from AIDS-related pneumonia.

For Blake, the book was an inspiration. “As soon as I read ‘Days of Grace,’ it has always been my answer to what’s your favorite book of all time,” he told Moutoussamy Ashe.

Young officiated at Ashe’s funeral in Richmond, which was attended by thousands of mourners. He was buried alongside his mother, Mattie, who died in 1950 when he was just six years of age.

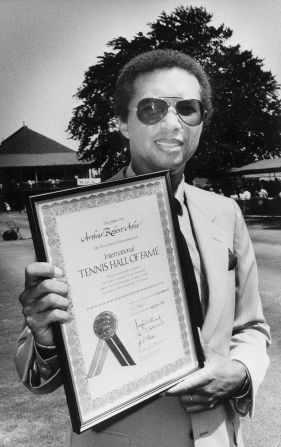

Later in the year that he died, Ashe was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton.

It was the first of a string of high profile honors in recognition of a truly remarkable man, but for his widow, who has carried his torch now for so many years, it is his impact on communities and the younger generation which is so important.

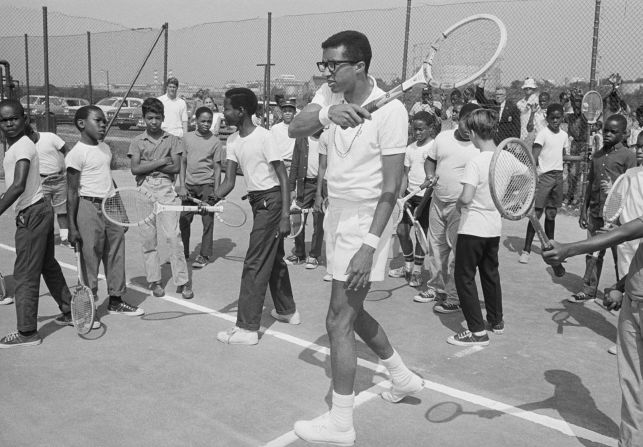

“I think if Arthur were here today, he would promote tennis on a grass roots level, drawing that metaphor that tennis not just a sport, but more importantly, a profession that might be able to get you a college scholarship to get you through school,” she said.

Others like Blake and Mal Washington followed in Ashe’s footsteps on the male side of the men’s game, but Moutoussamy Ashe is equally delighted by the impact the Williams’ sisters have had on African American sport.

“Venus and Serena, I’m so proud of what they are both doing. Venus has her challenges yet she’s moving her life forward and still stays very involved in the game of tennis whenever she can.

“Serena has been I think on top form, not just in tennis but as a person during this particular US Open,” she added, reflecting on the world No.1’s 17th grand slam singles crown.

Moutoussamy Ashe is hoping the Arthur Ashe Learning Center, which contains a wealth of her own photographs and memorabilia collected over his life, can find a permanent home.

“It’s really important that not just today’s generation but generations to come understand him as more than just an athlete, as more than just a patient, as more than just a student and a coach.

“That they’ll understand the importance of being a well-rounded human being, that you might not be a great champion, but if you’re a well-rounded human being, then you can do just about anything to succeed in life.”

Ashe himself is the perfect example of that, battling his modest background and an undercurrent of prejudice to achieve the highest honor that can be bestowed on an individual in the United States.

“Racism is not an excuse to not do the best you can,” Ashe said and he stands eloquent testimony to the truth of his words.