Story highlights

Exclusive interview with Boeing unit that handled the Dreamliner fix

Boeing built mockups of 787 battery bay

Work was tedious rather than onerous, Boeing says

Fix involved multiple parts of Boeing's enterprise

It was a monumental challenge, a logistical effort Boeing had never faced before: simultaneously moving a small army of technicians to 13 international locations, transporting 15 tons of tools per repair kit, and installing newly designed equipment in the field, taking five days per airplane working around the clock in two 12-hour shifts.

The goal: get 50 new 787 Dreamliners back in service as quickly as possible following a three-month grounding.

Boeing’s pride had been stomped on by the first ever grounding of one of its airliners. Pride and a commitment for customer service meant going all out for five disappointed, sometimes cantankerous customers.

The task fell to Boeing’s Commercial Aviation Services, or CAS, to complete a task unprecedented in its scale. Elements have been revealed by Boeing’s chief 787 program engineer, Mike Sinnett, in various press conferences.

Below is the inside story of the planning process, the first time CAS has granted an interview about its planning and implementation process.

Outlining how CAS reacted to the two now famous lithium-ion battery incidents is the head of CAS, Louis J. Mancini, senior vice president, and James Testin, managing director of AOG (Aircraft On Ground) Aircraft Services. I spoke with them at the company’s Commercial Airplane headquarters in Renton, Washington.

Single ‘meltdown’ to worldwide grounding

The first incident involved Japan Air Lines on the ground at Boston Logan Airport on January 7. There was a battery meltdown, a “propagation” of eight cells, followed by a fire, which was confined to the electronics bay where the battery was housed.

CAS was already planning to repair the JAL 787 when another battery incident occurred January 15 on an airborne ANA flight shortly after takeoff in Japan. An emergency landing and evacuation followed. Inspection revealed another propagation incident, but this time no fire.

What began as a typical repair reaction by CAS to the JAL incident became an international crisis a day later on January 16 when the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration grounded the six U.S.-registered 787s operated by United Airlines. Regulatory authorities worldwide followed suit.

CAS’s AOG unit knew immediately after the ANA incident it would be facing a monumental task, driven by the sheer scope and scale of the impending logistics.

“I would call this not a simple job, but a straightforward job,” Mancini says.

“Jimmy’s (James Testin’s) team thought a lot about laying it out so we could get as efficient as possible. Compared with ripping a landing gear off or part of a wing off or replacing a rear pressure bulkhead, I would call that very serious work. This is more the large-scale logistics of it all.”

Within days of the ANA event, Testin’s AOG team realized they would need to construct a mockup of the 787’s electronic bay on the ground. They also would construct a mockup in a 787 on the flight line at Everett (WA), where planes were waiting delivery and where more were coming off the production line.

This work began in parallel to the research, development and design that ultimately involved thousands of employees across the Boeing “enterprise” and from battery experts outside the company.

“It wasn’t serial,” Mancini says. “During that process it was becoming pretty clear there would be a series of steps: changes to the battery, changes to the charger, changes to the vent tube, the enclosure. Jimmy’s team started engaging about halfway through as certain details got more refined. There was more clarity and preciseness to the event. We started bringing in Jimmy’s team early on so he could start formulating his plans and actions.

“The worst thing would have been to wait for everything to be done and say, ‘here, Jim.’”

Multiple skillsets

“Within CAS we had enough personnel to do what we needed to do [to install the fix],” says Testin.

“However, because of the way the teams were going to have to be built, there were some very specific skills that were needed. A good example would be engine run. Within AOG we have two engine run folks but obviously we were going to need more, so we did reach across the enterprise.

“We reached out to our BDS (Boeing Defense, Space and Security) counterparts. We reached out to our factory. We reached out to our avionics functional test guys and the Everett flight line people really helped. A vast majority of it came from the Everett flight line. They are as close to the same skill set as we would require.”

BDS employees are military specialists but a large group worked on the difficult birthing of the 787 during the four-year program delay.

“It’s not like we had to train them,” Testin says. “They had already been trained and they were current on a lot of their training.”

Engine run is starting up the engines for a short time in order to complete tests and take readings. It is also important when “waking up” an airplane that hasn’t been operational for some time – such as the case of the Dreamliners that had been grounded for several months.

“We were treating Logan as a one-off event,” Testin says. “[We] were trying to understand the damage. As the other events began to unfold, then we stepped back and said we need to take what we are doing right now and figure out how we do that on an expanded level.

“Once the grounding occurred, then we said we need to take this to the next step, to build the mockups, we need to go out on the flight line and figure out how this is going to go.”

“We immediately began working with the 787 program to understand where they were headed, what they were thinking and to go out on the flight line and to understand some of the scenarios. The engineers would say this is what we think it is going to look like, this is what we believe are the areas we’re going to affect.

“Space was a huge deal. I would say that within two weeks we began to assemble that [mockup] room. We also had a live mockup out on the flight line.”

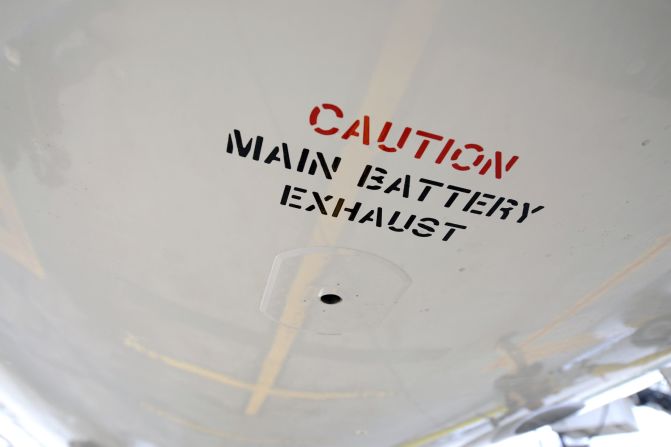

Boeing designed a “robust” fix that includes separating battery cells, a new charging system, venting and a containment box.

‘Tedious’ fix

The fix itself is far from the most complex job CAS has done in the field.

Boeing has in the past changed pressure bulkheads, grafted an entire nose onto an airplane and repaired badly damaged aircraft in the field.

It’s not unique to Boeing: all aircraft manufacturers have to support their customers. Airbus had to undertake difficult and lengthy aircraft repairs for the A380 involved in an engine explosion over Singapore that badly damaged the wing, structures and components. Airbus also had to replace the entire tail of an A340 damaged in a takeoff accident in Australia.

Testin said the installation of the fix wasn’t onerous, but tedious.

“We were worried about the logistics. Three hundred people around the world when you have 10 teams out, that’s a pretty large package for us to do. The traveling behind it, moving the equipment. We had to go out and purchase the equipment to get multiple units.”

The parts easily go into a lower cargo hold but the tools and logistics to do the work are more suitable for a freighter, Testin says. The equipment weighs close to 28,000-30,000 lbs.

“We have to take everything that we need with us, kitted by crew size. Once we determined what a crew size would be, we matched that up with kit. Hand tools, power tools. One kit would take up a good portion of a lower lobe on a 777.”

“This was on such as large scale, this is probably the single largest thing we had to focus on, the logistics behind being able to accommodate the movement. We moved equipment sometimes several times to satisfy the customers.”

CAS’s 10 teams fanned out to Asia, Europe, Africa and the United States while awaiting the FAA review of the design and fix. Approval came April 26. The first 787 returned to service within days.

The last of the aircraft are expected to return to service next month.