Story highlights

Some venues in Beijing celebrate the Cultural Revolution

Cultural Revolution has been largely erased from official discourse on China

Some decry the Cultural Revolution, while others are nostalgic about it

The East is Red restaurant is unlikely to end up in many international guidebooks as a must-visit destination in Beijing.

Sitting on the outskirts of the Chinese capital city, the eatery chose its moniker after the famous Maoist song of the same name and is themed around China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-76), an era which many would rather forget.

And yet on any given night of the week, the restaurant gathers a large and boisterous crowd.

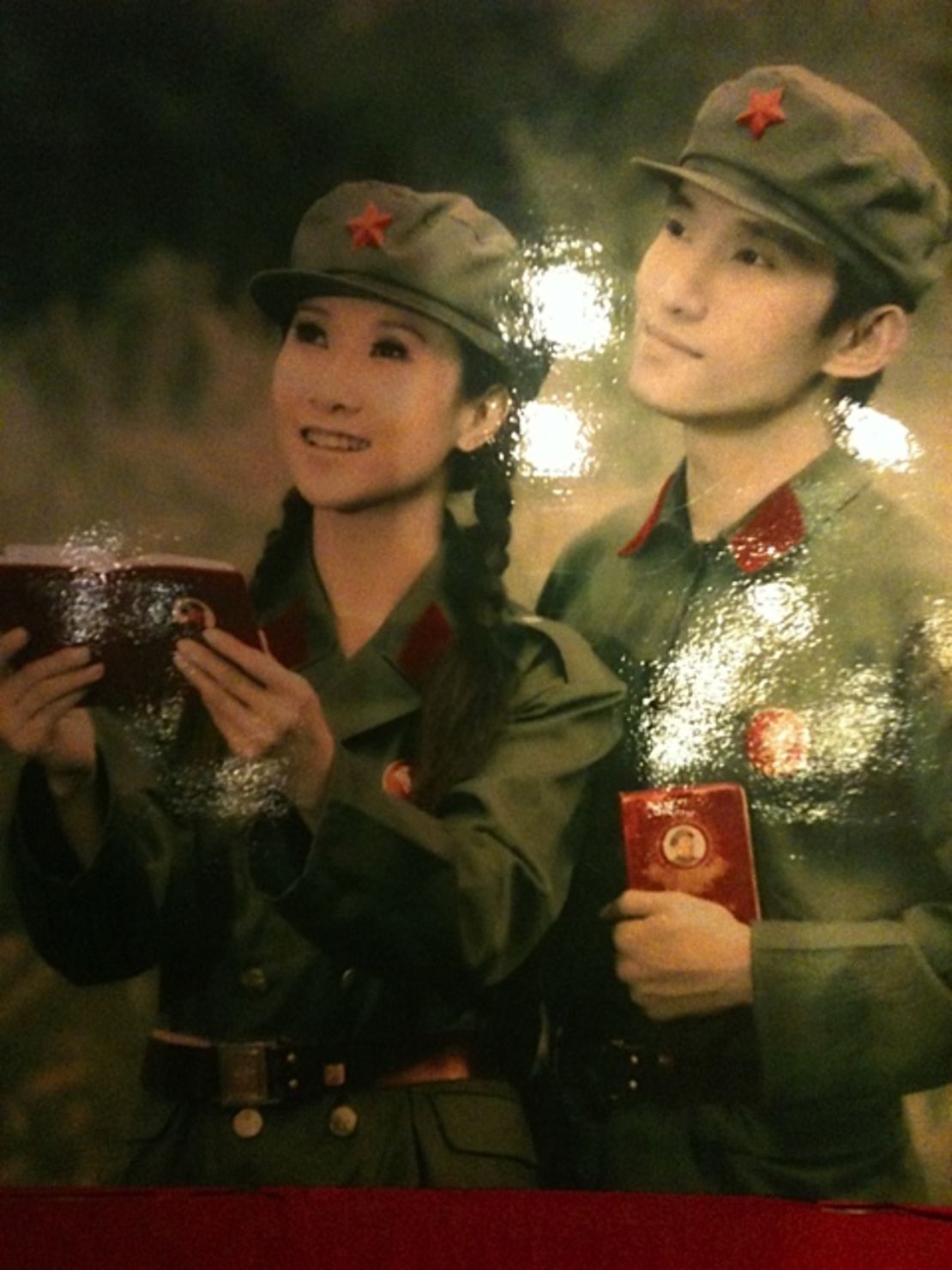

Waiters race around dressed as red guards, the student army force of the time. Revolutionary posters decorate the walls and red flags deck the tables. The central draw is a stage, where entertainers sing “red” revolutionary songs and perform mock struggle sessions. People in the audience cheer and sing along; some even cry.

The East is Red is just one of many venues in Beijing that gives the Cultural Revolution a makeover, repackaging what was once a tragedy into a gimmick. Some have been kicking around since the late 1990s, while others are more recent additions.

“It was really exciting,” commented 26-year-old Yin Hang of his recent trip to one. “Everything was new to me. I knew a bit about that part of history from my parents but I don’t feel a connection to it.”

It seems strange to use this period of Chinese history as entertainment. After all, the Cultural Revolution, which was Mao Zedong’s political campaign aimed at rekindling revolutionary zeal, saw violence spread throughout the country. By its end an estimated 36 million had been persecuted, with at least 750,000 of those killed in the countryside alone. Countless historical relics were destroyed, and universities closed, depriving many young people of years of education.

Though the Cultural Revolution has been largely erased from official discourse on the People’s Republic, its horrors relegated to an appendage in history books. Those who did not live through the Cultural Revolution know it was a difficult time, but few grasp the extent. This historical amnesia might explain why some young Chinese in particular can enjoy the venues.

“China’s historical memory is very barren, so even recent events can fall through a gap,” said James Palmer, a longtime China watcher who visited one of these venues as part of field research for a book he wrote on the death of Mao, whose passing away marked the end of the Cultural Revolution.

“If you detach it from the political context it is just fun, like a Tudor-themed bar in England,” Palmer added.

But Palmer also sees more to the trend. Although people are critical of the Cultural Revolution, the era isn’t only remembered for its destruction. Memories are mixed. “While a lot saw the time as horrific, enough people had a good experience and associate the period with a sense of freedom and youth,” Palmer said.

This is especially the case for those who came of age during the era, such as Zhang Mei. Zhang was born in 1957 and has lived in Beijing her whole life. During the Cultural Revolution she enjoyed traveling around the country for free, and divided her time between school and youth parades. For her, these venues provide an avenue for nostalgia.

“When I went to the restaurant they called me ‘comrade’, the common greeting of the time. It felt intimate,” Zhang said, adding that the singing made her happy because the ballads belong to her generation.

However, not all look at the Cultural Revolution through red tinted spectacles. Sasha Gong, who co-wrote The Cultural Revolution Cookbook (2011), is one of them. For Gong, the book was written not to capitalize on the trend to consume positive aspects of the Cultural Revolution, but rather to educate the masses about all aspects, good and bad. “Even though the Cultural Revolution is very recent history, people don’t know much about it. This is especially the case in the West, where they can romanticize it,” Gong said.

Gong was part of the sent-down youth movement at the time, which saw thousands of children taken away from their parents and sent to work in the countryside. Writing the book was “a cathartic experience – a way to go back to a recent, difficult period,” she said. “The Cultural Revolution was terrible, one of the worst human experiences anyone can have.”

Gong admits the irony of writing a cookbook about a period that had little food. But even though it was a time of austerity, her generation learned how to cherish food and create delicious, healthy dishes.

In this respect Gong shares something in common with another group of people who visit these venues in Beijing. They are those who hark back to a time, real or imagined, that they deem better than contemporary China. Cultural Revolution food might be tainted by unpleasant memories, but at least it was not tainted by pesticides.

And for some, especially the post-Mao generation, they feel ambivalence not just towards current food, but also current politics.

“The Cultural Revolution is essentially a religious experience, an ideological break from the China of now. They associate the government today with materialism and believe the government stance that the Cultural Revolution was bad is just propaganda,” said Palmer of this group, who are labeled neo-Maoists.

Among the most notorious of Beijing’s neo-Maoists is Fan Jinggang, who was born in 1976 and currently manages the Utopia bookstore, a shop that specializes in books praising the late Chinese leader and his policies, and criticizing reform era capitalism. Earlier this year, Fan got into trouble due to his support of Bo Xilai’s revival of “red culture” in Chongqing.

Bo’s policies involved the employment of nostalgic Maoist propaganda and a harsh crackdown on businessmen accused of corruption. They gained him notoriety, as well as enemies, who attacked them as throwbacks to the Cultural Revolution.

In the days immediately following Bo’s removal from his post as head of Chongqing and Party Secretary on March 15, Fan was paid an unfriendly visit by the authorities. The popular website attached to his bookstore has since been suspended.

CNN was unable to reach Fan to ask his thoughts on the Cultural Revolution, but in an interview with Chinese site Danwei back in April, Fan is quoted as saying, “…some traitors in the Party betrayed communism and created all sorts of rumors to attack Chairman Mao.”

Despite these recent events, the atmosphere at Utopia remains upbeat, as does the atmosphere at other venues that market the Cultural Revolution in Beijing. Perhaps they simplify and trivialize the era. However, they still bring people closer to an otherwise rarely mentioned period of recent Chinese history, and in so doing, shed light on China today.