Story highlights

- The 19th International AIDS Conference is in Washington this week

- This is the first time in 22 years that the conference has been in the United States

- Global researchers are developing priorities for finding a cure

This week, the world's largest gathering of AIDS doctors and experts is converging on Washington for the 19th International AIDS Conference. It marks the first time in 22 years that the biannual event will be held on U.S. soil, possible only because a 25-year-old travel ban preventing HIV-positive people from entering the country was lifted by President Barack Obama in 2009 and went into effect a year later.

The significance of that move is not lost on researchers all over the country. More than 25,000 doctors, scientists, AIDS activists, politicians, philanthropists, drug company representatives, people living with HIV and heads of state from around the world are attending the weeklong conference.

There's a lot going on: research on how to prevent HIV infection, treatment as prevention and, for the first time in a long time, talk about a "cure."

In fact, one of the main themes is the launch of "Towards an HIV Cure": a global scientific strategy by an international working group of 300 researchers who are developing a road map of sorts, outlining priorities for finding a cure for the disease that has claimed approximately 30 million lives worldwide.

Their goal: figuring out why the virus lives indefinitely in certain cells, which tissues it lives in, how to get the immune system to kill it and what kind of drugs can get rid of it.

"We are trying to both inspire people about the possibility that this might happen someday but trying to be realistic, and the realistic part is that we have to do some fundamental basic science first," said Dr. Steven Deeks of the AIDS Research Institute at the University of California, San Francisco. "Most reasonable people would say it's at best 50-50 that we're gonna get a cure, so we don't want to over-hype this. We're excited, we think it's possible, we think it's worth pursuing, but don't expect anything in the near future."

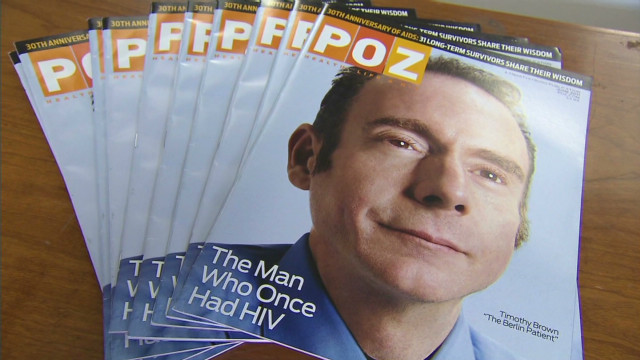

One man in particular, Timothy Ray Brown, has pushed the limits of possibility. He's known as the Berlin patient, the only person said to have been "cured" of HIV/AIDS.

"I've been tested everywhere possible," said Brown, who now lives in San Francisco. "My blood's been tested by many, many agencies. I've had two colonoscopies to test to see if they could find HIV in my colon, and they haven't been able to find any."

In 2007, Brown, an HIV-positive American living in Berlin, was battling leukemia and needed a bone marrow transplant. His doctor searched for a donor with a rare mutation that makes it resistant to HIV. The transplant not only cured his cancer, it appears to have cured his HIV, because the virus is no longer detectable.

But Brown's case is rare. The procedure is extremely dangerous because a patient's immune system has to be wiped out in order to accept the bone marrow transplant. Using a bone marrow transplants to treat HIV is not a feasible treatment for most patients; only 1% of Caucasians -- mostly Northern Europeans -- and no African-Americans or Asians have this particular mutation, researchers say.

Last month, five years after Brows was "cured," reports surfaced that traces of the virus had been found in his blood. Deeks says that doesn't matter.

"Clinically, he has been cured. He stopped his drugs five years ago, his HIV tests are turning negative, we cannot find with standard measurements or even really super-sensitive measurements any virus anywhere, so from a clinical perspective, he is cured," Deeks said. "There's an academic debate as to whether every single virus is gone, but from Timothy's perspective, he shouldn't care."

Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is one of the foremost experts on HIV and AIDS and believes that Brown's case is a "proof of concept" that the battle against the disease can advance beyond daily drug cocktails.

Deeks leads the global collaboration with Dr. Francoise Barre-Sinoussi of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine for the discovery of HIV, along with her colleague Luc Montagnier. She says that by working together, they can get the job done faster.

"What we are sure is that we think it's reasonable today to say it's feasible to have a cure. A functional cure. I believe that if we work like in the early years of HIV, all together, we can move forward very fast as well for an HIV cure."

But what will a cure look like? There are two schools of thought. With a "functional" cure, the virus is controlled, and transmission would not occur. A "sterilizing" cure would eliminate the virus from the body entirely.

On Wednesday, Dr. David Margolis, an AIDS researcher at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, is presenting results on a small study of eight patients treated with Vorinostat. It is used to treat lymphoma, a cancer of the lymph nodes and bloodstream.

"We just have to start doing these studies and trying to make progress, and I think the big change in the last few years is that you can talk about it now, and we can start to work on it seriously rather than doing the scientific work surreptitiously but not using the 'cure' word because everybody thought that was irresponsible or ridiculous."

Margolis says everything is on the table to try. "The assumption is, it's going to be complicated and difficult and involve multiple approaches, not 'take a pill and we're done.' "

French researchers are studying 12 HIV-positive people called the Visconti patients. According to Barre-Sinoussi, they were treated immediately after being exposed to HIV and have been able to control their virus naturally. Promising results from that study will also be presented.

"These patients have been treated very early on by the classical antiretroviral treatment during the acute phase of infections. They stopped their treatment, and now they are naturally able to control their infections with treatment anymore. They remain HIV-positive but they don't transmit to others, so it's also prevention."

Researchers also hope to learn some important lessons from a group of infected men and women called elite controllers.

"They do not irradiate their virus," Barre-Sinoussi said. "But they are capable to naturally control their infection because they never receive any antiretroviral treatment. They have an undetectable viral load."

While small trials like these aim to find a cure, efforts to prevent infection have also made great strides. Last year, multiple studies showed that transmission of the virus can be reduced significantly -- up to 96% -- by giving antiretroviral drugs to the uninfected partners of people with the disease. It's called PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis.

For Barre-Sinoussi, all the pieces of the puzzle are important to future success, and she is hopeful of a cure in her lifetime.

Brown, who believes that he is cured, is banking on it.

"It means that this is a case in point that the disease can be cured. I don't wish what I went through on my worst enemy, but I'm hoping that it can be done in a more simple way, that can be translated to a cure for the entire world, all people that have HIV."