Story highlights

The 1976 Montreal Olympics almost left the city bankrupt with its US$1.48 billion-price tag

But former IOC vice-president Dick Pound said the games were hailed as a sporting success

The city retained and invested in its sporting facilities long after the Olympics finished

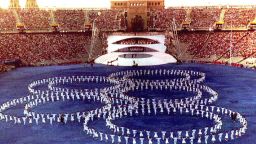

Montreal’s Olympic Stadium is known as the “Big O,” but for many of the city’s taxpayers it is really the “Big Owe.”

“It took us 30 years to pay it off and as a taxpayer I’m not too happy about it,” said one Montreal resident, echoing the anger that many here still feel about the way the games were funded in 1976.

“It was not very well managed as a financial project. And we have a fabulous stadium, but I think it cost more than all the covered stadia in North America put together, ” said Dick Pound, former International Olympic Committee vice-president and a prominent resident of the Canadian city.

However, Pound said calling the Montreal games of 1976 “the bankrupt Olympics” is a bad rap, and pointed out that the games actually made money. He said they paved the way for a new financial structure and the introduction of lucrative new television rights deals.

People still come up to him and remember how well the Montreal games were staged and, in the end, how exciting they were, he added.

“They were pretty magic. All Olympics are magic but we had Comaneci with her first ’10’ and we had the Spinks brothers and we had Sugar Ray Leonard,” he said.

“I mean we had some magnificent heroes of the modern Olympics.”

But there is weariness in Montreal about being known for staging the Olympic games that almost bankrupted a city. The city’s mayor at the time, Jean Drapeau, famously remarked that if the games end up having a deficit, men will have babies.

And it was in large part due to the Olympic Stadium construction that the statement seems so ridiculous now. The Olympic debt was nearly US$1.48 billion, and the stadium itself has been an engineering nightmare – the retractable roof has struggled to worked properly over the years and almost forced the closure of the entire arena last year amid safety concerns.

But the city’s current government insists Montreal has put that legacy behind it and the Olympic stadium is now a key attraction.

“Now it is paid, and it’s profitable for Montreal to keep it,” said Manon Barbe, the councillor in charge of sports and leisure for the city.

Barbe pointed out that the legacy of the games has created a sporting city that nurtures hundreds of elite athletes.

“Today Montreal has more than 1,000 elite athletics and more than 100 coaches. And if it’s that high, it’s not a coincidence. It is because we decided to keep most of our sporting facilities,” said Barbe.

One of those facilities is the Claude Robillard Sporting Center, an impressive training facility for more than a dozen sports that nurtures athletes of all ages. During the 76’ games, the center hosted handball and water polo and was a training center for athletics, swimming and field hockey.

Today, hundreds of aspiring athletes receive access to coaching and equipment, much of it subsidized by the city of Montreal.

On most days you will find former Canadian Olympian Hank Palmer here on the track, either indoors or outdoors, or training in the pool or weights room.

“If I didn’t have this center, I probably wouldn’t be at the peak I am, I would not have the career I’ve been able to have,” said the sprinter, who competed at the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

“This center really helped me develop myself, not only as a track athlete but an athlete in general because I have so many other sports around me.

“I can cross-train, do basketball, soccer, weight training, anything.”