Story highlights

Hong Kong marks 15 years since the handover from British to Chinese rule

The island became a British colony after the first Opium War in 1842

Britain and China agreed that Hong Kong should remain independent for 50 years

Hong Kong has its own borders, laws, currency and freedom of expression

In 1842, when Hong Kong became a British crown colony after the first Opium War, it was described by a very unimpressed UK Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, as a barren rock with nary a house on it.

He also added, prophetically and spectacularly incorrectly, “it will never be a mart for trade.”

Of course, by 1997, when Hong Kong was handed back by the British to become a Special Administrative Region (S.A.R) of China, it was a modern metropolis of well over six million souls, used to a free economy, a free press and the rule of law.

According to the agreement hammered out between Britain and China, the territory would remain that way for at least 50 years.

Under Chinese rule, Hong Kong would govern itself, choose its own leaders, control its own economy and maintain its own legal system. But there were many skeptics. Would China really be able to keep its hands off?

Fifteen years later, almost a third of the way through those 50 years, are those promises still being kept? How has the territory changed?

Christine Loh has a unique perspective. She was a legislator during the last years of the British colony and again in the early years of the Hong Kong S.A.R. A feisty democrat politician, no one would ever accuse her of being in the “pro-Beijing” camp.

If you look at the people of Hong Kong, she said, their daily lives really haven’t changed very much.

Indeed, Hong Kong has its own borders and immigration control, even with China. It has its own currency, its own police force and system of law courts. It has freedom of expression and demonstration to a degree unheard of anywhere on the mainland. It’s the only place in China, for example, that can commemorate the June 4, 1989 crackdown against the students in Tiananmen Square.

The territory also has its own legislature and chief executive. Beijing has always promised to be hands-off, allowing the Hong Kong people to rule Hong Kong, but many still feel it has undue influence in local politics and in an electoral system that favors pro-Beijing candidates.

China’s huge presence is inescapable.

“Our unease in Hong Kong is that the mainland is so big and we are so small. We are a small city of seven million people. It is easy for us to be physically overwhelmed. I think that is our fear,” Loh said.

Since the handover, trade ties between Hong Kong and China have strengthened so much so that Hong Kong is now the mainland’s biggest source of foreign investment, state news service Xinhua reported, quoting China’s ministry of commerce.

Hong Kong is also the top destination for investment from the mainland. Trade between the two surged nearly 600% to US$284 billion from 1996, the year before the handover, and last year, Xinhua said. And ties are only set to strengthen.

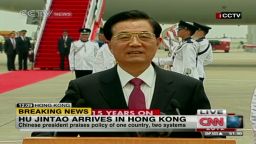

In the days leading to the 15 year anniversary, China announced a package of policies to further bind the mainland and the island covering trade, finance, education science and technology and tourism.

But the prospect of tighter ties with their homeland is not necessarily being welcomed by Hong Kongers, many of whom feel that while Chinese money has boosted business, it has also put pressure on public services.

Earlier this year, full page advertisements appeared in the local media, bluntly calling mainlanders “locusts” and accusing them of driving up property prices and squeezing Hong Kongers out of their own hospitals and schools.

“We have a love-hate relationship with China,” said Hong Kong entrepreneur Douglas Young, whose popular chain of stores selling furnishings and knick-knacks celebrates a unique Hong Kong style.

He is adamant that Hong Kong should hold onto its differences.

“I disagree that you have to choose between being a Hong Kong person or a Chinese person. I am both. Like a New Yorker, a New Yorker is both a New Yorker and an American, and I am a Hong Konger as well as being a Chinese person,” Young said.

“So I think there is nothing wrong with Hong Kong being a part of mainland China or being a Chinese city. All I am saying is that Hong Kong should maintain its differences in its regional identity.”

CNN asked people on the streets of Hong Kong what the difference was between Hong Kongers and the Chinese.

“Many of us were educated in Western countries and went abroad for a university education so naturally our cultural background is different from those Chinese nationals who were born and raised in China,” one man said.

“I don’t know much about China,” one woman said in Cantonese. “The problems in China right now make me think that I should not consider myself Chinese,” she added.

However, one woman who described herself as a Chinese person who was born in Hong Kong said, “Hong Kong people and Chinese people are basically the same. The only difference between the two is that they are born in different places.”