Story highlights

Amnesty International's annual report on global human rights lauds the courage of protesters

There has been a failure of leadership by the world's politicians, says Amnesty chief Salil Shetty

The U.N. Security Council has failed to intervene to protect ordinary people, he says

Activists around the world helped make 2011 a "truly tumultuous year," Amnesty says

Like many other 18-year-olds, Nina Siren is on the point of graduating from high school. Unlike her peers, she has spent more than half her short life fighting to prevent the destruction of her home, culture and indigenous community in the interests of oil exploration.

Zimbabwean women’s rights activist Jenni Williams, 50, has been arrested 43 times in the course of peaceful protest activities and now faces criminal charges she says are trumped up by the authorities.

Omar Assil, who took part in protests in Damascus last year before leaving his homeland for the UK, now works with other young Syrians to give nonviolent support for the pro-democracy movement.

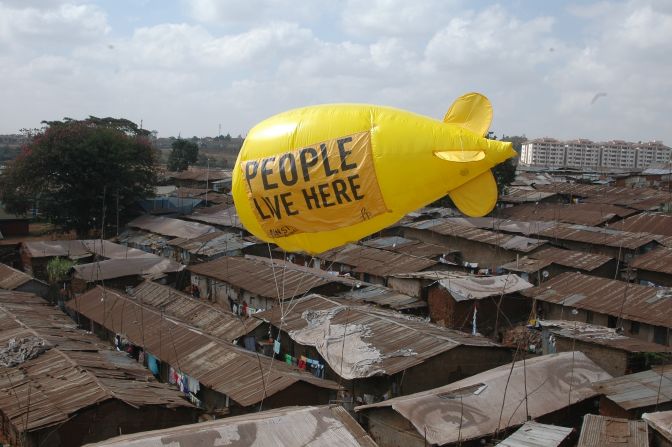

They are just three of the protesters who through their actions have helped make 2011 a “truly tumultuous year,” in the words of Amnesty International’s 50th annual report on the state of global human rights, released Thursday.

The dramatic scenes of the Arab Spring have kept protesters in the Middle East and North Africa in the headlines, especially as voters in Egypt take part in a landmark presidential election this week.

But Amnesty also lauds the often unseen efforts of demonstrators elsewhere in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas last year.

At the same time, the rights group is scathing in its criticism of a “failure of leadership” at local and international level, saying those in power have left protest movements to fend for themselves as they take on tyranny and injustice.

“Failed leadership has gone global in the last year, with politicians responding to protests with brutality or indifference,” said Salil Shetty, Amnesty International Secretary General, launching the report in London.

“Governments must show legitimate leadership and reject injustice by protecting the powerless and restraining the powerful. It is time to put people before corporations and rights before profits.”

Shetty singled out the U.N. Security Council for its failure to act effectively in both Syria and Sri Lanka, saying it left the body seeming “tired, out of step and increasingly unfit for purpose.”

“In the last year it has all too often become clear that opportunistic alliances and financial interests have trumped human rights as global powers jockey for influence in the Middle East and North Africa,” said Shetty.

“The language of human rights is adopted when it serves political or corporate agendas, and shelved when inconvenient or standing in the way of profit.”

Forced to move from a remote corner of the Ecuadorian Amazon to Sweden four years ago amid death threats following her community’s opposition to the planned oil project, Nina Siren has been part of the fight to preserve the way of life of the indigenous Kichwa people of Sarayaku since she was 7 or 8 years old.

That was when she heard a representative of the oil company that wants to develop their community’s pristine land – a project Amnesty says is backed by the government – offer just $60,000 in return, or roughly $15 per person.

“I was just a child but I understood that I would never give up my land,” Siren said.

“I wanted to ask him why he was trying to give me $15 to destroy my land and drive me out of there. I think that was the first moment when I realized that this was going to be a very long struggle.”

For four years after they fled to Sweden, it was too dangerous for the family to return to their homeland.

“To know we couldn’t go back to see my family, my village – it was horrible, horrible,” said Siren, who is now able to travel home once or twice a year.

But despite the obstacles they have faced, Siren and her mother, Noemi Gualinga, have helped take their community’s decade-long battle all the way to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica.

Now they are anxiously awaiting its judgment, expected in the coming months.

That verdict could impact on thousands of indigenous communities in Ecuador and beyond who want their governments to adhere to international human rights law that requires them to consult with indigenous peoples before giving developments on their land the go-ahead.

Gualinga said the arrival of oil companies on their land would have meant “the end of our culture and our way of life.”

The indigenous community has used the Internet to get its message out to the international community, Siren said, in an echo of protest movements elsewhere.

And witnessing the Arab Spring movement has helped the Sarayaku people in their struggle.

Young upstarts plotting Mid East art revolution

“I feel very inspired when I see in the news other people doing similar things to us,” said Gualinga. “Before we used to feel very alone … and now we can see that we are not the only ones, so that definitely brings hope.”

For Jenni Williams, the revolutions of the Arab Spring have been both an inspiration and a driver for the Zimbabwean government’s increasingly harsh crackdown on protests at home.

As executive director and founding member of Women of Zimbabwe Arise (WOZA), she leads a movement of 80,000 human rights activists who seek to improve the everyday lives of the southern African nation’s women.

She accuses the authorities under President Robert Mugabe, who has ruled Zimbabwe for 32 years, of misusing their powers to suppress protest and hold onto power, through arrests and intimidation.

“That’s how these dictators are entrenching themselves, and we, the activists, have to find a response to that,” Williams said. “How do you dodge a bullet and make a ballot count?”

Amnesty International’s report highlights the arrests, detention and torture of human rights defenders by a partisan police force who, it says, failed to take action against members of Mugabe’s ZANU-PF party when they “harassed, intimidated or beat up perceived political opponents.”

“The Arab Spring has been an inspiration, but since that we’ve been viewed as a national security threat,” Williams said. “We are a women’s movement using peaceful protests but it has (led to) increased monitoring, surveillance and charges against us.”

Nonetheless, she and others will continue to make a stand for justice and equality for women, she said.

Omar Assil of the Syrian Non Violence Movement is similarly determined, despite the unrest that continues to wrack Syria more than a year after the government’s crackdown on protest first began.

“We see that people are still demonstrating, they still have hope for change, and they still insist on going out in the streets regardless of all the danger they face,” he said.

Amnesty International says “inaction over crimes against humanity in Syria” – owing in large part to the vetoes wielded by Russia and China – has left the U.N. Security Council” looking redundant as a guardian of global peace.”

And it challenges the United Nations to do better when it meets to agree an Arms Trade Treaty in July, saying this is the “acid test for politicians to place rights over self-interest and profit.”

Millions of people around the world have marched in defense of human rights, Amnesty says, and it’s time for the world’s leaders to step up to the plate.

“Protesters have shown that change is possible. They have thrown down a gauntlet demanding that governments stand up for justice, equality and dignity,” said Shetty, Amnesty’s secretary general.

“They have shown that leaders who don’t meet these expectations will no longer be accepted. After an inauspicious start 2012 must become the year of action.”