Story highlights

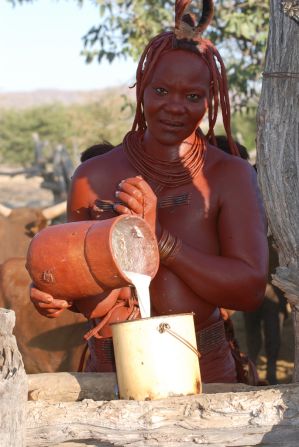

The Himba women of northwest Namibia are renowned for their use of otjize

Otjize is a paste of butter, fat and red ochre which is applied to their hair and skin

The Himba communicate with their god and their ancestors through a holy fire

For years, an ancient tribe of semi-nomadic herders known as the Himba has drawn photographers to Namibia’s barren northwest.

As a result, the striking image of the Himba – if not their name – has become known far beyond the remote, unforgiving Kunene region where they eke out a living tending livestock.

The reason for this is otjize, a paste of butter, fat and red ochre – sometimes scented with aromatic resin – that Himba women apply each morning to their skin and hair, giving them a distinctive red hue. The sight of traditional Himba women has become an iconic image of Africa.

There has been much speculation about the origins of this practice, with some claiming it is to protect their skin from the sun, or repel insects. But the Himba say it is an aesthetic consideration, a sort of traditional make-up they apply every morning when they wake. Men do not apply otjize.

Although it is constantly jeopardized by development, including proposed hydroelectric projects, many Himba lead a traditional lifestyle that has remained unchanged for generations, surviving war and droughts.

These customs can be glimpsed today in the village of Omarumba, where around 20 people live under the leadership of chief Hikuminue Kapika. The Himba are open to outsiders coming to witness their way of life, but ask for a contribution from visitors in return – in this case, maize, coffee, tea, cooking oil and $25 donation.

As pastoralists, cattle are central to the lives of the Himba – just like their relatives, the Herero, who are renowned for the headwear of their women, which resemble cattle horns.

Read also: The Namibian women who dress like Victorians

In the center of the village is a pen where young cattle, sheep and goats are held, while more mature animals are left to roam the periphery. Every morning, after the women have applied their otjize, they milk the cattle, before the young men of the village lead them out to graze. If there is nowhere to graze, the village may relocate, or the young men set up a temporary village with their stock.

The past year has been dry, says Uvaserua Kapika, one of the chief’s wives, and the village is concerned about the welfare of their livestock.

“Last year, it rain(ed) a lot and I was very comfortable. This year, I don’t know what to say… I pray to God as the animals are dying.”

The homes of the Himba, who number between 30,000 and 50,000, are round structures constructed of sapling posts, bound together to form a domed roof which is plastered in mud and dung.

The most important part of the Himba village is the “okuruwo,” or holy fire. Kept continuously alight, the holy fire represents the ancestors of the villagers, who acts as intermediaries to the Himba’s god, Mukuru. The chief’s is the only house whose the entrance faces the fire – all the others face away – and it is important for outsiders not to walk in the sacred area between his house and the fire.

Read also: ‘Stolen’ African skulls return to Namibia

At night, an ember from the fire is brought into the chief’s hut, then used to kindle the flames again in the morning.

Chief Kapika said he would regularly sit by the fire to interact with his ancestors. “We pray for rain to come and our cattle to multiply,” he said. “He must bless me with more followers as a chief.”

Said his wife, Uvaserua Kapika. “This is the place we pray to our God in heaven. In this place, you can get healed. Everything is performed here.”