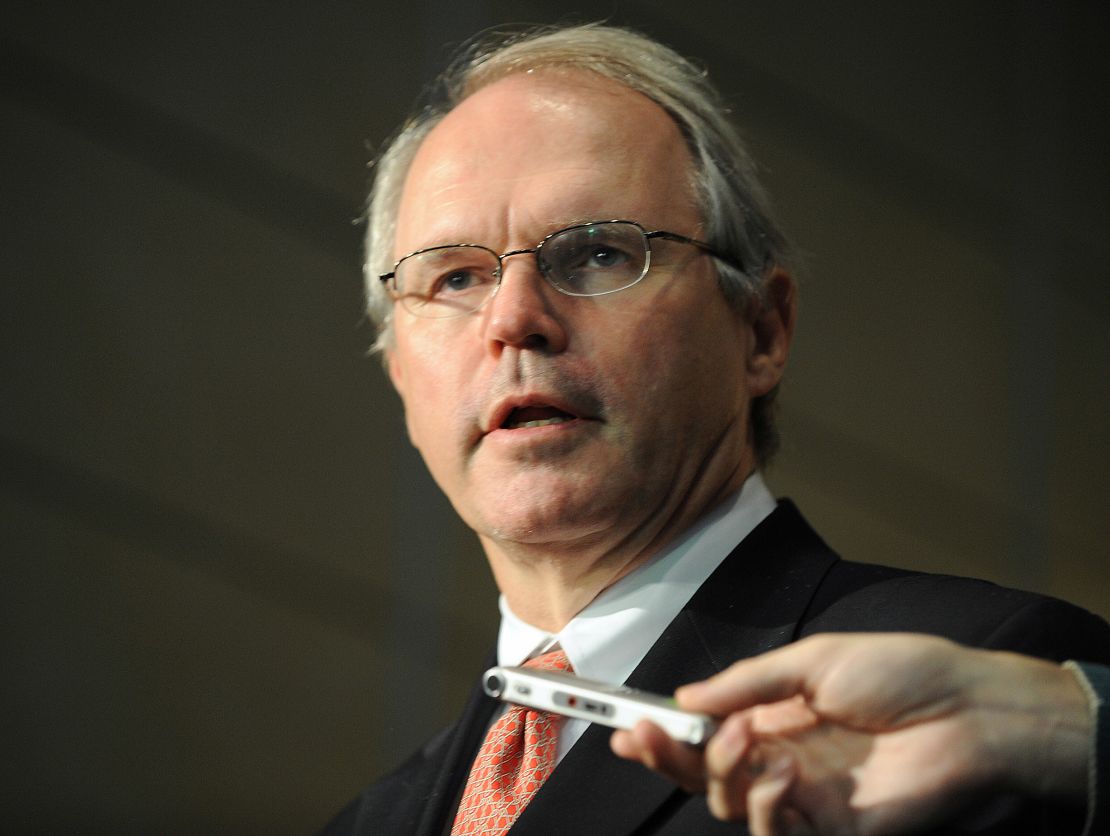

Editor’s Note: A former U.S. ambassador to Iraq, Poland and Macedonia, Christopher R. Hill also served as the country’s envoy to South Korea in 2004-2005. As Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, he was lead U.S. negotiator at the Six-Party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue in 2005. In 2010 he was appointed Dean of the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver.

Story highlights

North Korea says it plans to launch a rocket carrying a satellite this month

Other countries say the move is a cover for a ballistic missile test

Hill: U.S. must work closely with its regional partner to resolve the crisis

The collapse of an earlier deal hints at internal struggles in N. Korea, Hill says

In the next week North Korea will launch a satellite to coincide with the 100th birthday of Kim Il Sung, the late “Great Leader,” and the man perhaps most responsible for the reclusive state’s status as the world’s most irresponsible country.

But Kim’s “birthday present” also means North Korea’s people will have to forgo 240,000 metric tons of food aid from the United States, as well as the prospect of further negotiations aimed at bringing their country in from the cold.

There are no good options for how we should respond. There never are with the North Koreans. But working closely with our partners is a good place to start. We must ensure the launch strengthens our partnerships rather than weakens them.

It is difficult at this point to assess what happened to make the North Koreans essentially renege on the deal. Many analysts have made the case that this is typical North Korean behavior. That is true, but with an important caveat: The North Koreans usual way of doing things is first to pull out of a negotiation over some issue that would not be an issue among normal countries, but becomes a deal breaker for this “exceptional nation.”

North Korea parades launch pad for world media

After a period of time, the North Koreans tend to follow up their effective walkout with a provocative act such as a missile test. In the case of the February 29 agreement, however, the negotiations had hardly broken down. By all accounts the atmosphere was good. The process was very much on track, and – dare one use a word that should not be used in the context of North Korean negotiations – there was optimism. Optimism that finally the momentum was being cranked up.

Another far more spurious explanation has been to blame the victim, in this case, the United States. The idea is that the U.S. negotiators, having conducted months of painstaking preliminary work including with the Chinese and the South Koreans, somehow failed to nail down a clear pledge from the North Koreans, to the effect that a so-called space launch would be on the proscribed list.

Obama warns against provocation

This farcical argument, prevalent among those who have convinced themselves that they would have been more competent than the U.S. negotiators, has been “confirmed” by the North Koreans themselves – surprise, surprise – who deny the launch was even mentioned in negotiations. Besides, the North Koreans view their space program as a kind of NASA of their own, and how could anyone think the launch was anything but their own contribution to the peaceful exploration of space?

A far more likely explanation is that – surprise, surprise – North Korea did not have its act together. The people negotiating the food aid were not the same as those launching the missile. Presumably, the rift was civil-military, with the former more interested in feeding its people than the latter.

One can imagine as well various conspiracy theories to explain the situation. After all, even dictatorships experience political struggles. With a free-for-all political scene, pitting the boy-dictator-wannabe, buttressed by his ambitious aunt and often antagonistic uncle, against a grouchy and arrogant military establishment, it could well be that the agreement was scuttled as part of an ongoing battle to settle personal rivalries. The standard of living in North Korea’s upper aristocratic nomenclature may not be much better than that of a Seoul taxi driver, but it’s state power that counts, not just the supposed access to luxury goods.

Some will say we have little choice but to wait and watch, and perhaps harvest the intelligence trove that may, so to speak, fall our way. Military solutions are least desirable, but so would be the prospect of a North Korean rocket falling on the soil of an ally, unopposed by an anti-missile system. We must protect our allies from a missile threat.

Looking beyond the immediate crisis, we need a strategy that addresses any concerns that America’s allies may have that our nuclear umbrella is not enough. We must continue to work closely with South Korea politically and diplomatically. We failed to do that in the early 2000s, with one consequence being that many South Koreans began regarding the North Koreans as our victims rather than one of the world’s miscreants.

We have worked closely with China, but perhaps it is time for that ambitious nation, so preoccupied by its internal affairs of late, to step it up and start attaching some sense of urgency to addressing the problems caused by its support for a country that would not last a week without it.

Above all, we need to remain patient and calm with the resolve to understand that we cannot walk away from the problem. We need to work with others and strengthen the regional partnerships we have – and will need – if the North Korean problem is ever to be solved.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Christopher R. Hill.