Story highlights

Concept designed to produce all food of a modern supermarket on one plot of land

Dutch architects say they will use mix of technologies to create artificial growing climates

Scheme designed to reduce food production and transportation emissions

Crop scientist has doubts about creating artificial microclimates

Big cities are rarely home to thriving farmlands, but a group of Dutch architects hope to change that with the “Park Supermarket” – an urban farming project that will attempt to grow and sell all the food of a modern supermarket in one place.

The firm behind the proposal, Rotterdam-based Van Bergen Kolpa Architects, intends to produce everything from risotto rice, to kiwis to Tilapia fish all on one 4,000-acre plot of disused land in Randstad, Holland’s largest metropolitan area.

In defiance of the country’s moderate climate, the architects say they have devised a system to control the park’s outdoor environment, using old and new farming technologies to simulate Mediterranean and tropical climates in an ecologically sustainable way.

The land, which had been earmarked for a large block of business developments before the global recession, cuts across the city fringes of Rotterdam and The Hague, serving a potential customer-base of over one million people, according to Van Bergen Kolpa Architects.

“The cities surrounding the proposed site are home to 170 different eating cultures – from Moroccan to Indonesian, from Turkish to Chinese – and we’re aiming to grow food to satisfy all their tastes,” said Jago van Bergen, an award-winning architect and one of the brains behind the “Park Supermarket” – which has been shortlisted for the upcoming World Architecture Awards in November.

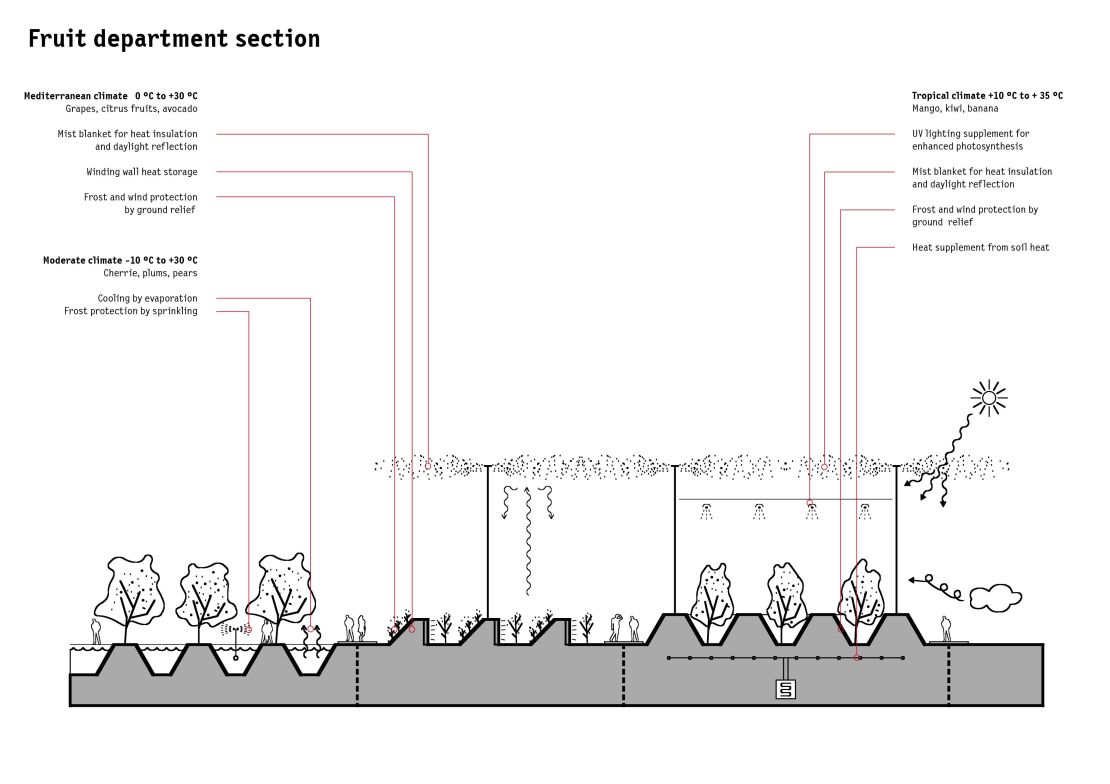

“The plan is to divide the park into three climate zones – moderate, Mediterranean and tropical. Because this will also be a recreational space, our goal is to make it as open as possible, without using greenhouses,” he said.

But how exactly do you create a warm outdoor microclimate on the urban fringes of a north European city? According to van Bergen, it’s not as far-fetched or futuristic as it sounds.

“The main differences between a Mediterranean and moderate climate are longer periods of light and warmth in the evening, ” he explained. “To make up this difference we’ll use a combination of traditional and modern farming methods that all work by trapping and storing heat and releasing it when temperatures drop,”

So, in an effort to grow typically Mediterranean foods like olives and peppers, for instance, van Bergen says he’ll need little more than rows of “snake walls” and “climate pylons.”

According to van Bergen, “snake walls”, made from clay, curve over crops helping to shield them from cold winds, while simultaneously emitting heat absorbed during the day.

“They used this method in the 18th century gardens of eastern Germany’s Potsdam, so the king could grow grapes to make wine that tasted as good as the French stuff,” he said.

“Climate pylons” are a more modern method of trapping heat. Van Bergen says they simply rain down a fine mist of water from high up, creating clouds that act like vapor roofs, stopping warm air from disappearing into the sky.

However, for tropical foods like mangoes and basmati rice, van Bergen says the park will need another layer of warmth.

“In this case, we’ll pump geothermal energy – heat stored deep in the lower soils – up to the top using underground pipes filled with water,” he explained.

“This technology is used in football stadiums to stop the pitches freezing over and more recently it’s being used to heat homes.”

Van Bergen concedes that the pumps and electric-powered lights that artificially extend daylight hours will require an additional input of energy, but claims that it will all be met by local renewable sources.

Read related: ‘Living’ buildings could inhale city carbon emissions

The Park Supermarket was commissioned by planning officials from the South Holland Province, and plans are afoot for a small test site to be up and running by the end of this year.

If successful, the firm believes this type of system could form part of a new approach to sustainable farming, making use of urban greenbelts while helping to reduce the carbon footprint associated with food production – which accounts for up to 30% of total emissions worldwide, according to a 2008 Greenpeace report.

“The dominant food-production system is based on fossil fuel at every level,” said Dr Martin Caraher, professor of food and health policy at London’s City University. “It needs oil to make the fertilizer, oil for the farm, oil for the food processing, oil for the packaging and oil to transport it to the shops,” he added.

Van Bergen says the park will reduce carbon emissions by cutting down on food processing and transport costs, while stimulating local industry and social bonds.

“Because all the food in our supermarket will be grown on site we won’t need a big processing factory to make packaging and we won’t have to burn lots of fossil fuel to transport it across the globe,” he said.

However, the Park Supermarket concept does not appeal to everyone.

“Anything that reduces food miles and other carbon emissions linked to food production is normally a positive thing,” said Dr Nicola Canon, lecturer in crop sciences at the UK’s Royal Agricultural College. “However, I have reservations about any system that creates open artificial climates.

“We know that we are suffering from climate change, with one area enduring long wet spells while another goes through a prolonged drought. I wonder if we really ought to be exploring technologies that seek to control our already unpredictable weather cycles.”

Canon is also concerned that the introduction of alien climates may also precipitate the introduction of alien pests.

“Every time you raise humidity, you raise disease affectability – because where you have good conditions for growth you also have good conditions for disease to grow. I think creating tropical climates next to moderate ones could introduce a host of new diseases and pests to the region in quite an unpredictable way,” she warned.

Finally, while Canon says she appreciates what van Bergen and his team are trying to do, she doubts that the system could be replicated on a wider scale.

“In my experience, it takes a lot of resources to create a relatively small microclimate. This means land that could otherwise be used for growing native crops is taken up with technology – whether it be rows and rows of snake walls or climate pylons or whatever,” she said.

For van Bergen, this type of criticism misses the point, because he sees the Park Supermarket as just one of many possible alternatives to the existing system of food production.

“I’m not a preacher of any one form of agriculture,” he said. “Just like our energy, I think our future food supplies will have to come from a variety of sources, using a variety of methods – of which we are sure this will be one.

“But this is about more than sustainable, non-intensive farming, it’s about cultivating community ties and giving new meaning to a space on the edge of the city that is currently being used for very little else.”