Chiara Zuddas and her 2-year-old daughter, Bianca, sit on a balcony at their home in San Fiorano, Italy, on February 28.

What life is like inside a coronavirus ‘red zone’

Photographs by Marzio Toniolo via Reuters

Story by Kyle Almond, CNN

Chiara Zuddas and her 2-year-old daughter, Bianca, sit on a balcony at their home in San Fiorano, Italy, on February 28.

Italy is on lockdown.

In an attempt to control the spread of the novel coronavirus, the government has imposed restrictions across the entire country.

Schools are shut down. Religious services have been suspended. Sporting events have been postponed. Public spaces are now empty. All stores are closed except for pharmacies and food markets.

And travel is heavily restricted.

“You cannot leave the house except for basic necessities and for work issues,” said Marzio Toniolo, a schoolteacher who lives in the small commune of San Fiorano. “In any case, it is necessary to have permits and self-certifications that attest to the actual urgency of our exits.”

Bianca Toniolo draws a picture of the coronavirus while she and her family stay at home.

Young Bianca has a picnic with a doll outside her home in San Fiorano.

Bianca plays at home.

San Fiorano is in northern Italy, where restrictions were first imposed in late February.

Toniolo has been documenting his family’s daily life since then, taking photos and videos for the Reuters news agency. He lives with his wife, Chiara; their 2-year-old daughter, Bianca; and his grandparents, Ines and Gino.

“On February 21, I realized that something would change our lives and I was right in the middle of it,” he told CNN via email. “I thought that I wanted to leave a tangible memory, visually, to us and our daughter.”

Residents of San Fiorano wear protective masks on February 24.

Empty shelves are seen inside a shop in San Fiorano on February 22.

Marzio Toniolo's car trunk is full of bags after a trip to a supermarket in Codogno, Italy, on February 25.

This week Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte announced that the coronavirus “red zone” in northern Italy was expanding to the entire country.

As of March 13, Italy had more than 15,000 confirmed cases of the coronavirus and more than 1,000 deaths. Only China, where the virus originated, has higher numbers.

Toniolo says people in San Fiorano have died.

“The community is small and we all know each other, therefore every time someone leaves us it is a pain that affects everyone,” he said.

Toniolo’s family prepares a meal at home on March 2.

Bianca hides behind a tree as she plays with her mother in an empty park on February 23.

Medical workers, some in protective suits, stand by an ambulance in Codogno on February 28.

Toniolo and his wife are both teachers. They continue to work with students online, sending lessons and activities.

That and his reportage for Reuters keeps Toniolo busy.

His wife spends much of her free time reading, cooking and working in the garden. And of course, young Bianca is getting a lot of attention.

“We told her the truth and tried to explain what's going on, as far as she can understand,” Toniolo said. “She follows the rules that we have taught her, because she knows that there is something that is dangerous for our health.”

Bianca has her hair brushed by her great-grandmother, Ines Prandini, on March 2.

A road is blocked in San Fiorano on March 8.

Prandini and her husband, Gino Verani, sleep at home on March 7. Toniolo’s grandparents are in their 80s.

There are military checkpoints along the main roads, and anyone who doesn’t follow the rules faces fines or even arrest.

But the hardest part for many Italians, Toniolo said, is having to keep their distance from one another, “not being able to touch people, embrace and kiss them.

“We have to keep our physical distances, which is not pleasant. You observe other people with suspicion or avoid them directly. And we were not used to all this.”

Prandini fills in crossword puzzles to pass the time.

Verani eats biscuits at home on March 3.

A shelf in the family's living room is dedicated to coronavirus supplies such as face masks and hand sanitizer.

Every morning, Bianca arranges her dolls, which are also in quarantine, in a line on the sofa.

Toniolo was told that by April 3 he’d be able to go back to work. But he finds that “unthinkable” at the moment. He expects that schools will be closed for longer and that it could take months for Italy to get past this stage.

He is trying to stay positive and look for the silver linings.

“The positive aspect is that you can spend your time to produce beauty. By drawing, writing, reading or playing an instrument,” he said. “We can stop to reflect on ourselves or take care of those around us.”

Members of a youth volleyball team wear face masks — and stand at least 1 meter apart — as they train in Codogno on March 7.

Men play cards on a street in San Fiorano on February 27.

Toniolo goes for a bike ride with his wife, Chiara, on March 7.

Toniolo says that while this crisis has created physical distance between people, it has also brought them closer in a way. He has felt “extraordinary empathy” among Italians all going through the same thing.

He looks forward to being able to be with others again.

“When everything ends, I would like to have a beer with my best friends. A simple thing,” he said. “And of course be able to be free to embrace them.”

Verani sits at home on February 22. His grandson says he suffers from dementia and that the lockdown has caused him additional confusion.

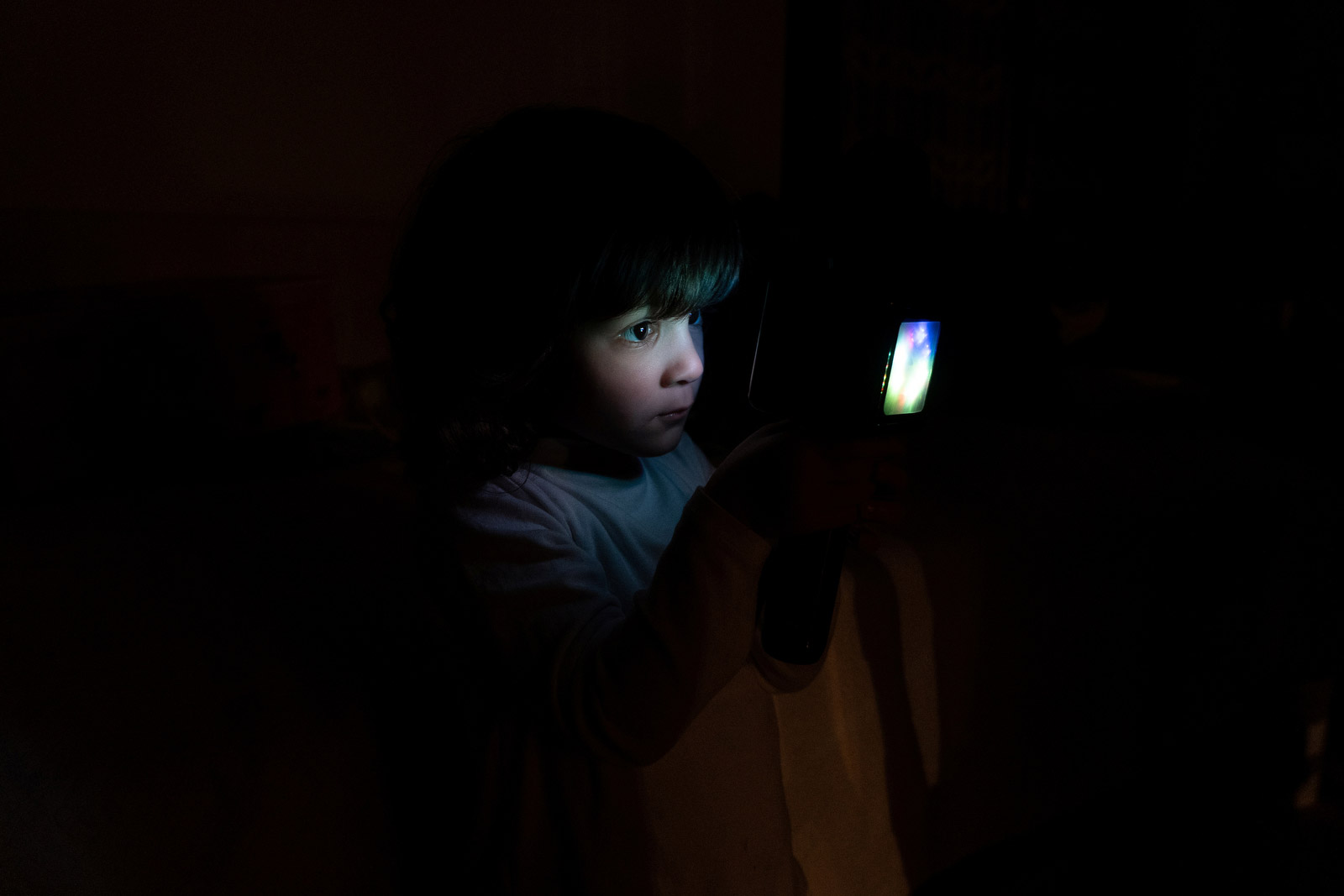

Bianca plays with a lit-up microphone on March 5.

Bianca waves at a train as it passes through San Fiorano on February 29. The driver beeped the train's horn in response.

Marzio Toniolo is a teacher who lives in San Fiorano, Italy. Follow him on Instagram.

Photo editor: Brett Roegiers