Editor’s Note: Rahwa Asmeron is a senior producer for CNN International. The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

The Saturday after my sixteenth birthday is a day I’ll never forget. That morning, I awoke to a loud commotion and walked toward the sound. My mom was wailing, my sister was screaming and my brothers looked like they’d seen ghosts.

I kept walking and saw that several fully armed soldiers were pointing their rifles at my family. The soldiers ordered me to stand next to everyone else, and soon a rifle was pointing toward me.

My dad then appeared at the top of the stairs. And there was a soldier behind him too. He led my dad outside and put him in the back of a military truck. No explanation given.

We didn’t know it at the time, but my dad would be one of the first Eritreans to be forcibly expelled from Ethiopia in 1998. A border spat between the two countries blew up into an all-out war that summer.

That conflict eventually killed an estimated 80,000 people, and it continued until this July, when Eritrea and Ethiopia declared that their “state of war” was over.

A few weeks after they took my dad, they came for my mom. She told the soldiers they’d have to shoot her if they didn’t let her bring her youngest child. My little brother was five at the time. He and my mom spent the night in prison.

The next morning, they were put into crammed buses and sent off on a three-day journey on a treacherous route. They were driven north, directly into the war zone. When they got to the border, the Ethiopian soldiers wanted to provoke the Eritreans into shooting up a bus full of civilians, so they started shooting in the air. Thankfully, their bus crossed the border sans bullet holes.

By the end of that summer, some 70,000 Eritreans and Ethiopians of Eritrean descent had been forced out the same way.

But younger Eritreans in Ethiopia had bigger worries than just being sent to a new country. If they went to Eritrea, they’d be forced into the army. And if they stayed, they feared the Ethiopians would jail them so they wouldn’t go fight for the other side. For this reason, countless people scrambled to leave, including the rest of my siblings.

A UN-brokered peace agreement paused the fighting in 2000. Part of the deal was to let an independent commission demarcate the border. The commission finished its work two years later and issued what was supposed to be a “final and binding” ruling. It awarded several territories, including the flashpoint town of Badme, to Eritrea, but Ethiopia refused to accept the decision.

So, for the last two decades, a tense stalemate has been the law of the land on both sides of the border. Eritrea had been independent from Ethiopia for just five years when the war began, so there hadn’t been much of a border before that. The sudden shutdown of that border meant countless families found themselves suddenly divided. Phone services cut off. Ground transportation halted and flights grounded – for 20 years.

Now, things are suddenly changing.

Within the last few weeks, leaders of those two countries have taken serious steps toward peace. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has only been in office since April, but he’s been enacting sweeping changes. His major foreign policy objective at the moment is peace with his northern neighbor. In June, he declared Ethiopia would finally accept the border ruling, essentially ending the 20-year stalemate.

A few weeks later, he hosted a high-level delegation of Eritrean officials. Shortly after that, Abiy flew to Eritrea, where he was treated like a rock star. Thousands lined the streets of the capital, Asmara, to get a glimpse of the man whom they credit with pushing their long-time stubborn leader toward peace.

A week later, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki was in Ethiopia. A packed and festive crowd awaited him – ecstatic because this leader’s presence on their soil meant he really was ready for peace. Before he returned to Eritrea on Monday, he was on hand to witness the reopening of his country’s embassy.

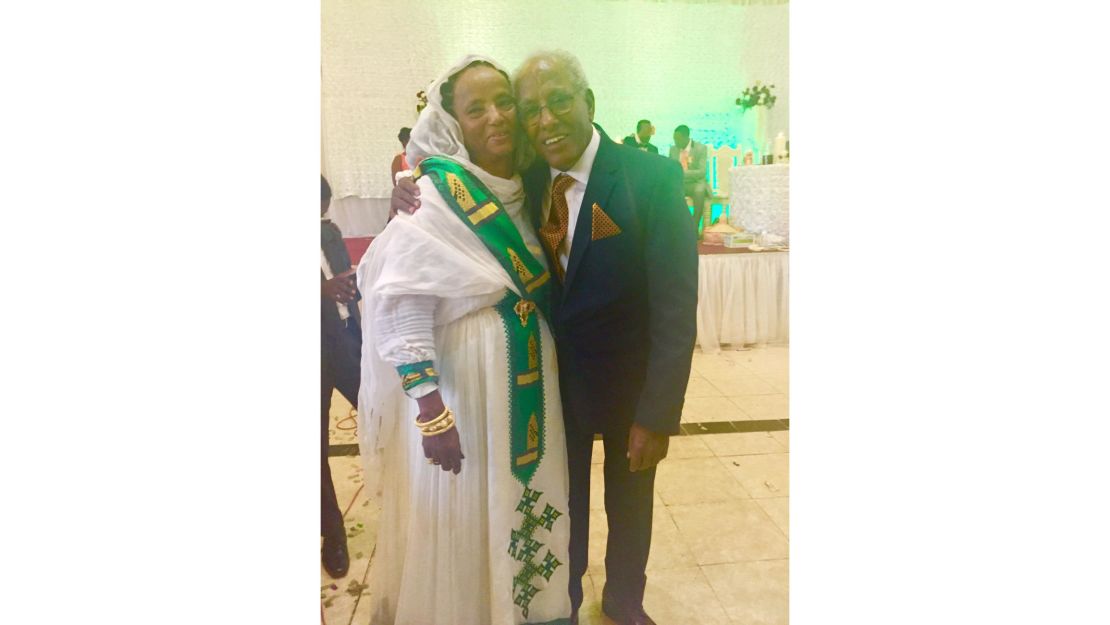

And it’s not just the leaders who are eager to travel. On Wednesday, there were emotional scenes at the airport in Asmara after the first commercial flight since the war landed from Ethiopia. One photo shows a man kissing the ground at his mother’s feet after having just seen her for the first time in more than two decades.

People I’ve talked to in both countries say there’s a sense of collective euphoria. For so long, people had felt helpless in their situation and hopeless for their future. Ethiopia’s population is about 100 million more than Eritrea’s, and its army is much bigger and better funded. Nonetheless, Eritrea had long used the border stalemate as the reason for indefinite conscription.

There had been sporadic clashes at the border, and Eritrea wanted to be ready if war broke out. That threat is now dissolving, and things seem to be getting back to where they used to be.

Along with the relief that peace is on the horizon, there’s also a layer of bitterness. That it took this long to figure out that both sides didn’t want to fight. So many lives lost, upended and disrupted for 20 years and no good reason. All wars are stupid, but this one especially so.

The hope now? That peace will hold. That young people don’t risk their lives to get to Europe. That families will reunite. That politicians will keep their word. That a silly dispute over a dusty little border town won’t cause another deadly war. That this reconciliation can be an example for other disputes that seem so intractable.

Both countries have plenty of other internal issues to work on. International organizations have long decried human rights violations and lack of press freedoms. So, as they work on regional peace, perhaps they can tackle other problems together.

At a concert on the eve of the Eritrean President’s departure from his historic visit to Addis Ababa, Abiy delivered a passionate speech about his hopes. “Forgiveness frees the consciousness. When we say we have reconciled, we mean we have chosen a path of forgiveness and love.”

My hope is that he’s right.